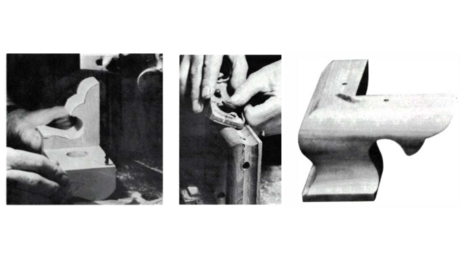

Synopsis: The cabriole leg has been produced by furniture makers in thousands of variations since its heyday in the 18th century. This collection shows how the furniture makers of today are putting a new spin on the cabriole. These updated versions range from the subtle, stretched version created by Ted Blachly, to the twinned cabrioles and innovative joinery of Jere Osgood, to the whimsical legs James Schriber used on his wood-and-metal side tables.

The cabriole leg was like a flourished signature on furniture of the 18th century. From Queen Anne through Chippendale, the S-curved cabriole, with its outcurved knee and incurved ankle, was produced by European and American furniture makers in thousands of variations, on pieces from dining tables and side chairs to highboys and footstools. But use of the cabriole—which takes its name from the Italian word for a leaping goat—neither started nor stopped in the 18th century. Versions of it have been around since ancient Egypt, Greece, and China. And now many furniture makers are giving it a contemporary twist of their own.

The reversing curves of the cabriole can provide a powerful visual impact whether the legs are long or short and whether the curves are sharp or shallow. The challenge for the furniture maker is to create a handsome cabriole that also suits the overall design of the piece. Here is a handful of examples that show how the ancient cabriole is being deftly put to use by some of today’s top makers.

Smoothed out and stretched

“I think subtle can be powerful,” says Ted Blachly, and the slightly sinuous legs of his table prove the point. The legs are notable not only for their restraint but also for combining a fairly hard line down the outside corner with softly rounded inside faces.

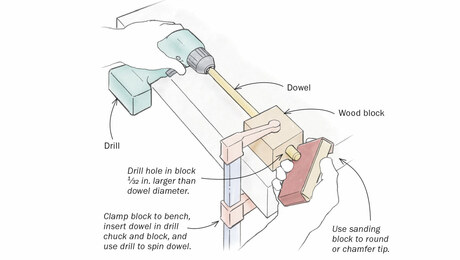

Blachly’s design started with a small freehand sketch and proceeded to a full-scale drawing. To generate the lines of the legs’ curves full size, he used a spline and spline weights. This simple technique, an essential in a boatdesigner’s kit, involves placing a thin, flexible strip of solid wood (the spline) right on the drawing paper and bending it to the desired curves. A few weights placed strategically along the spline hold it still while you trace the curve with a pencil. The longer the curve, the thicker the spline should be, Blachly says. For these legs, he used a cherry spline about 3⁄16 in. thick and 7⁄8 in. wide. To ensure that the spline takes an even curve when bent, it should be made from straightgrained stock. Specially made spline weights can be purchased (woodenboatstore.com; no. 835- 073S), but Blachly improvises with blocks of soapstone.

From Fine Woodworking #212

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Ridgid EB4424 Oscillating Spindle/Belt Sander

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in