Synopsis: Alan Stirt says working from the log is not only cheaper and more available, but it also gives you an opportunity to fit sizes and grain patterns to your own requirements, rather than accepting material that has been milled to a predetermined size. You can get larger sizes, and the material will be in better condition. Stirt details how to find a good supply of blanks and how to turn the wood while still green, so that will dry faster and with fewer defects than when in a solid chunk. He details each step of turning the wood to make a bowl, the best drying methods he’s found, and finish-turning dried bowls.

A big problem in bowl turning is obtaining thick, wide, dry wood. You might be able to get 4-1/2 or 5-inch thick mahogany or 4-inch teak from an importer. In the Northeast you might find some 3 or 4-inch maple, birch or cherry at local mills. These planks usually contain numerous checks and splits. If they are sound, they will be more expensive than thinner material. If you want to turn a number of bowls, such sources will be quite frustrating in terms of cost and available species.

However, green (unseasoned) wood can readily be found and is often free. Even exotic woods are much cheaper when bought in the log. Working directly from the log gives you an opportunity to fit sizes and grain patterns to your own requirements, rather than accepting material that has been milled to a predetermined size. Green planks also offer advantages over dry wood. You can get larger sizes (the sawyer won’t mind cutting extra-thick planks if he knows that he won’t have to dry them), and the material will be in better condition.

In rural areas, logging waste — often containing the most figured wood — sawmill slabs and storm-damaged trees are usually free or sold cheaply. Firewood piles yield nice chunks of local hardwoods. Small local mills usually are glad to cut logs to whatever dimensions you want. Here in northern Vermont, mills charge $40 to $50 per 1,000 board feet for milling logs that you bring them. If you buy a log from the mill and have it cut, the cost is 20 to 30 cents per board foot. If the log is in good condition, such material is virtually check-free. Even in cities, green wood can be had from local tree-removal services and highway departments.

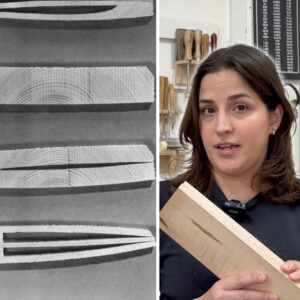

After you’ve found a supply of green wood, you have to dry it. One way is in planks or bowl-size blocks, but this is unlikely to produce perfect material. The easiest method is to turn the wood when it’s green. Once the wood is in a bowl shape it dries much faster and with fewer defects than a solid chunk. You might start with a slab of lumber 4 or 6 inches thick, but if you turn the walls of the bowl down to an inch, it dries more like 4/4 stock. The analogy isn’t exact because the grain orientation of the bowl isn’t the same as that of milled lumber, but proper drying procedures minimize the differences.

From Fine Woodworking #3

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

CrushGrind Pepper Mill Mechanism

JessEm Mite-R Excel II Miter Gauge

Bessey EKH Trigger Clamps

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in