Synopsis: Water is always present in wood, so an understanding of the interrelationship between water and wood is fundamental to fine woodworking, writes wood technologist R. Bruce Hoadley. Here, he explains water or moisture content in wood and its relationship to relative humidity and shrinkage and swelling. The extensive article includes charts showing the average moisture content of green wood and approximate shrinkage from green to oven-dry moisture content. There are instructions for calculating wood shrinkage or swelling, humidity graphs, and photos of problems associated with drying, such as checking, warping, etc.

What is the relative humidity in your workshop? Or in your garage where you are “seasoning” those carving blocks? Or in the spare room where you store your precious cabinet woods? Or for that matter, in any other room in your house or shop?

If you’re not sure, you may be having problems such as warp, checking, unsuccessful glue joints, or even stain and mold. For just as these problems are closely related to moisture content, so is moisture content a direct response to relative humidity. Water is always present in wood so an understanding of the interrelationships between water and wood is fundamental to fine woodworking. In this article we’ll take a look at water or moisture content in wood and its relationship to relative humidity, and also its most important consequence to the woodworker—shrinkage and swelling.

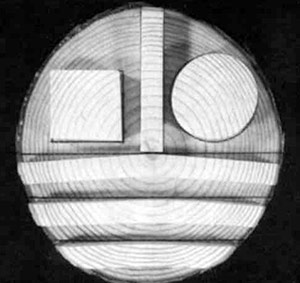

Remember that wood is a cellulosic material consisting of countless cells, each having an outer cell wall surrounding an interior cell cavity (see Fine Woodworking, Summer 1976). A good analogy for now is the familiar synthetic sponge commonly used in the kitchen or for washing the car. A sopping wet sponge, just pulled from a pail of water, is analogous to wood in a living tree to the extent that the cell walls are fully saturated and swollen and cell cavities are partially to completely filled with water. If we squeeze the sopping wet sponge, liquid water pours forth. Similarly, the water in wood cell cavities, called free water, can likewise be squeezed out if we place a block of freshly cut pine sapwood in a vise and squeeze it; or we may see water spurt out of green lumber when hit with a hammer. In a tree, the sap is mostly water and for the purposes of wood physics, can be considered simply as water, the dissolved nutrients and minerals being ignored.

Now imagine thoroughly wringing out a wet sponge until no further liquid water is evident. The sponge remains full size, fully flexible and damp to the touch. In wood, the comparable condition is called the fiber saturation point (fsp), wherein, although the cell cavities are emptied of water, the cell walls are fully saturated and therefore fully swollen and in their weakest condition. The water remaining in the cell walls is called bound water. Just as a sponge would have to be left to dry—and shrink and harden—so will the bound water slowly leave a piece of wood if placed in a relatively dry atmosphere. How much bound water is lost (in either the sponge or the board), and therefore how much shrinkage takes place, will depend on the relative humidity of the atmosphere.

From Fine Woodworking #4

From Fine Woodworking #4

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Ridgid R4331 Planer

DeWalt 735X Planer

AnchorSeal Log and Lumber End-Grain Sealer

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in