Synopsis: R. Bruce Hoadley talks here about how to dry wood found after storm damage, construction site clearance, firewood cuttings, and obtained directly from local loggers. The target in drying is to get the wood moisture content down to the equilibrium level of dryness consistent with the atmosphere in which the finished product will be used. Hoadley talks about shrinkage, end-grain vs. side-grain drying speed, marking and piling the lumber, and how to select or control conditions to allow for better drying. He shares tips on how to prevent it from drying too fast, and he warns against getting too much green wood at once.

It is ironic that our environment has us surrounded by trees—yet wood seems so inaccessible and expensive for the woodworker. Actually, abundant tree material is available to those who seek it out from such sources as storm damage cleanup, construction site clearance, firewood cuttings and even direct purchase from local loggers. With chain saws, wedges, band saws and a measure of ingenuity, chunks and flitches for carving or even lumber can be worked out. Also, it is usually possible to buy green lumber, either hardwood or softwood, at an attractive price from small local sawmills.

But what to do next? Many an eager woodworker has produced a supply of wood to the green board stage, but has been unable to dry it to usable moisture levels without serious “degrade” or even total loss. Certainly, the most consistent and efficient procedure would be to have the material kiln dried. Unfortunately, however, kilns may simply not be available. The cost of custom drying may be prohibitive, or the quantity of material too meager to justify kiln operation. But by understanding some of the basic principles of drying requirements and techniques, the woodworker can dry small quantities of wood quite successfully.

The so-called “seasoning” of wood is basically a water removal process. Wood in the living tree has its cell walls water saturated and fully swollen with “bound” water and has additional “free” water in the cell cavities. The target in drying is to get the wood moisture content down to the equilibrium level of dryness consistent with the atmosphere in which the finished product will be used (Fine Woodworking, Fall 1976). In the Northeast, for example, a moisture content of about seven percent is appropriate for interior cabinetwork and furniture; in the more humid Southern states, it would be higher; in the arid Southwest, lower. Since removal of bound water is accompanied by shrinkage of the wood, the object is to have the wood do its shrinking before, rather than after, the woodworking.

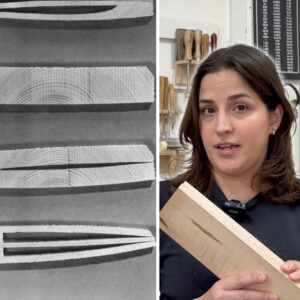

Wood dries first at the outside surface, creating a moisture imbalance. This moisture gradient of wetter interior and drier surface zone is necessary to cause moisture in the interior to migrate to the surface for eventual evaporation. On the other hand, if a piece of wood is dried too quickly, causing a “steep” moisture gradient (i.e., extreme range between interior and surface moisture content), excessive surface shrinkage will precede internal shrinkage; the resulting stress may cause surface checking or internal defects (collapse or later honeycomb).

From Fine Woodworking #5

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

DeWalt 735X Planer

AnchorSeal Log and Lumber End-Grain Sealer

Ridgid R4331 Planer

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in