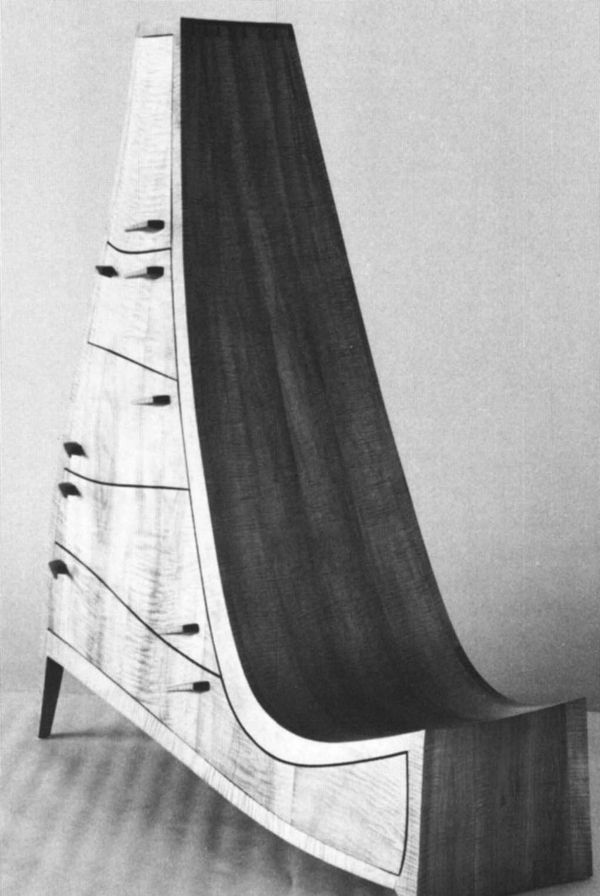

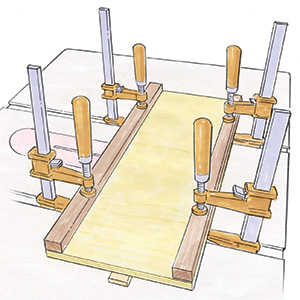

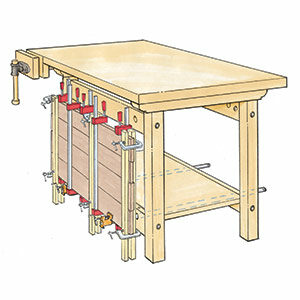

Synopsis: In this, the first in a series of articles about bent lamination, Jere Osgood focuses on basics, such as how laminations differ from veneers. Lamination is an economical way of achieving curved forms. Osgood explains how to forestall warp and offers general rules, such as keeping layers of the maximum thickness that will take the desired bend, as opposed to many thin layers, which risk surface unevenness. He recommends slow-setting glue for a lot of layers or for a large surface area, and talks about other glues for various purposes. The article includes information on building forms, and lots of drawings show how the wood bends during the different processes.

Samples of laminated wood have been found dating from the 15th century B.C. Lamination means a layering process. All the layers are aligned with the grain going in the same direction, and are held fast by a glue. Thin slices of wood can be laminated flat or to a curved form.

It is important to distinguish lamination from veneering. The grain of the laminate layers is always oriented in the same direction. In contrast, in veneering or plywood the grain directions alternate and an odd number of layers must be used. In lamination the layers, when glued together, will act like solid wood, expanding and contracting across the long grain. In veneering, grain alteration stabilizes the unit and there is no movement across or with the grain. Another form of lamination, stacking, is really a separate subject. (See “Stacking,” Fine Woodworking, Winter ’76.)

Furniture-related examples of lamination are flat or curved cabinet panels, tabletops, and curved leg blanks. The simplest lamination is the use of a fine figured wood as an outer layer on a tabletop or cabinet panel.

In many cases I find laminations more acceptable than solid construction. For example, one plank of an unusual figured wood could be resawn into many layers. These could perhaps cover all the sides of a cabinet, if backed up by layers of wood of lesser quality or rarity. If used at full thickness, many planks of this unusual wood would be needed to achieve the same effect.

Lamination is an economical way of obtaining curved forms. Members can be thinner when laminated as opposed to sawn because of the inherent strength of parallel grain direction. Steam bending is of course an alternative for curves and is an important process. However, lamination offers the advantage in many cases of more accurate reproduction of the desired curve. Modern glues have eliminated the bugaboo of delamination—the glue lines are as strong as the wood itself. An excellent use of laminated wood is in chair or table legs where short-grain weakness might inhibit design. It is important in some cases to make the layer stock thick enough so that any shaping or taper can be done in the outer two layers because going through the glue lines might be unsightly. In addition to counteracting short-grain weakness, laminating a curved leg also saves scarce wood, because a laminated leg can be cut from a much narrower plank than would be required for sawing the curved shape out of solid stock.

From Fine Woodworking #6

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Estwing Dead-Blow Mallet

Bessey K-Body Parallel-Jaw Clamp

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in