Synopsis: Exterior doors are required to perform three functions: seal off an opening from the exterior air, open to allow passage and then reseal, and be attractive. In this article, Ben Davies describes methods of construction that don’t work and how the frame-and-panel style excels. He prefers blind dowel pins to through-the-cheek pins in the mortises and tenons, and explains why. He describes raised panels and decorative elements like stained glass. He details sticking and moldings and formulas to help design door dimensions. Side information by Tage Frid discusses the right way to hang a door.

Exterior doors are the problem child of architectural design. They are required to perform three functions: seal off an opening from the exterior air, open to allow passage and then reseal, and be attractive. All this from wood, a material that can change in size as much as an inch over the width of a typical opening. While each of these functions might be separately accomplished with ease, their combination into one design creates problems.

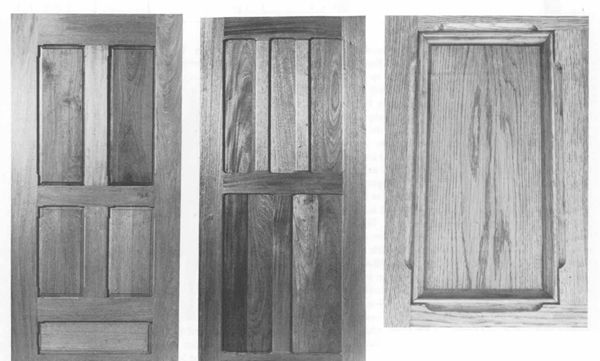

Single-panel board-and-batten constructions of edge-glued lumber are generally too unstable for exterior doors. They cast or wind unless great care is taken in the selection and seasoning of the lumber. They also expand and contract so much with the seasons that sealing against the weather is impossible. These shortcomings can be overcome by using frameand-panel construction and, in fact, most doors are made this way. The style is relatively stable and offers great flexibility of design. Even the familiar commercial veneered doors are a variation of the frame and panel—the panel is reduced in thickness to veneer and glued over the frame rather than inserted into grooves, and cardboard honeycomb or wood cores support the veneer. These doors succeed admirably in the first two functions a door must perform, but fail miserably at being attractive.

The frame-and-panel door has been in use for so long that its construction is well understood, and variations on its designs have been thoroughly explored. When any construction method remains dominant for hundreds of years it can mean only that it works quite well.

The standard size for entrance doors of new construction in the United States is 3 ft. wide by 6 ft. 8 in. high. A walnut door of this size can weigh 80 lb. to 100 lb. or more, depending on the thickness of the panels and the amount of glass. This is considerably heavier than a softwood or hollow-core door of the same size, and great care must be taken to ensure that the joints are well designed and well constructed.

I have seen a number of doors fail that were constructed with a mortise-and-tenon joint pinned through the cheek with dowels. A stronger joint is one with blind dowels inserted into the end of the tenon and bottom of the mortise. I use a 3-in. deep mortise and tenon with three or more 1/2-in. diameter blind dowels to join the stiles with the rails. Interior parts of the frame, such as muntins, are joined to the rails with smaller tenons, usually made to fit the groove cut for the panels, and are also blind-doweled.

More on FineWoodworking.com:

- How to Fit an Inset Door – Systematic approach tields perfect results every time

- A Simple Door Pull of Copper and Wood

- Where Door Meets Door – Minimizing the gap between stiles, choosing and installing appropriate hardware

From Fine Woodworking #9

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Stanley Powerlock 16-ft. tape measure

Festool DF 500 Q-Set Domino Joiner

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in