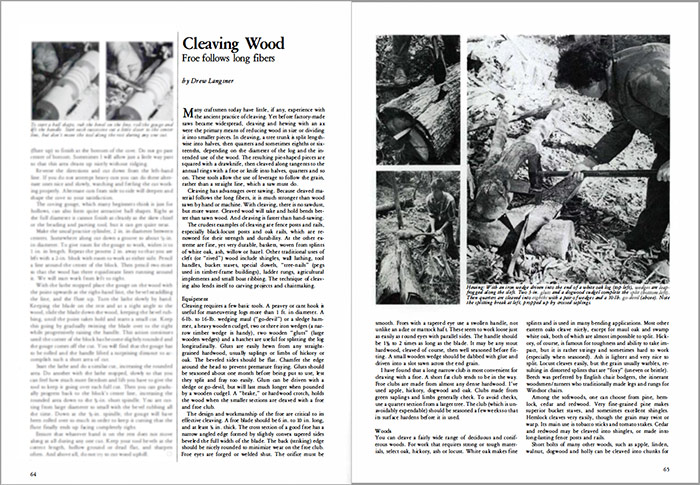

Many craftsmen today have little, if any, experience with the ancient practice of cleaving. Yet before factory-made saws became widespread, cleaving and hewing with an ax were the primary means of reducing wood in size or dividing it into smaller pieces. In cleaving, a tree trunk is split lengthwise into halves, then quarters and sometimes eighths or sixteenths, depending on the diameter of the log and the intended use of the wood. The resulting pie-shaped pieces are squared with a drawknife, then cleaved along tangents to the annual rings with a froe or knife into halves, quarters and so on. These tools allow the use of leverage to follow the grain, rather than a straight line, which a saw must do.

Cleaving has advantages over sawing. Because cleaved material follows the long fibers, it is much stronger than wood sawn by hand or machine. With cleaving, there is no sawdust, but more waste. Cleaved wood will take and hold bends better than sawn wood. And cleaving is faster than hand-sawing.

The crudest examples of cleaving are fence posts and rails, especially black-locust posts and oak rails, which are renowned for their strength and durability. At the other extreme are fine, yet very durable, baskets, woven from splints of white oak, ash, willow or hazel. Other traditional uses of cleft (or “rived”) wood include shingles, wall lathing, tool handles, bucket staves, special dowels, “tree-nails” (pegs used in timber-frame buildings), ladder rungs, agricultural implements and small boat ribbing. The technique of cleaving also lends itself to carving projects and chairmaking.

From Fine Woodworking #12

From Fine Woodworking #12

To view the entire article, please click the View PDF button below:

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in