Synopsis: Wood planks near the heart of the tree reveal the complete history of a tree, and these were the specialty of woodworker George Nakashima (1905-1990). He had hundreds of colossal planks waiting for projects, some hundreds of years old. Fine Woodworking‘s John Kelsey spent time with Nakashima and examines his philosophy, work styles and ideas, his biography, experience, and his work catalog. The detailed article describes how Nakashima’s career grew, and plenty of photos illustrate the breadth of his vision and design perspectives.

From Fine Woodworking #14

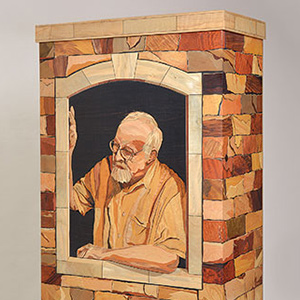

Scattered all over the world are landmark trees of great age and stature, monuments as old as civilization. They are usually past their prime, in the ordinary commercial sense, when they fall before advancing asphalt or the simple weight of age. They are discards, unless a woodworker like George Nakashima gets them. His aim, he likes to say, is to give such trees a second life as useful furniture, perhaps to fashion beauty, and by this work to achieve harmony with the natural forces that grew the tree in the first place.

Nakashima says he has spent the last 40 years getting to know lumbermen all over the world, buying English walnut and oak planted during the reforestation directed by Elizabeth I, Carpathian elm from Turkey’s border with Russia, American black walnut from New Jersey, teak, laurel and rosewood from India. He buys hundreds of logs a year and ships most of them to a band-saw mill in Maryland to be cut into planks. He likes to be there for the cutting, this ageless Druid, standing hands-in-pockets near the sawyer.

The huge log is maneuvered onto the saw carriage, gripped by heavy dogs, while Nakashima quickly figures where to cut and how thick. As with a diamond, the first cut commits you, success or firewood. He explains this to me in the gloom of his lumber shed, surrounded by monolithic planks standing on end. We are at the end of a long day of interviewing, in which he has stipulated an emphasis on his ideas and broad experience, not on technique. But now that we have finished the formalities, he loosens up and starts to tell how. He has been polite and controlled, and suddenly he is animated. He produces chalk to scribble the end view of a log on the face of a walnut plank, with the dogs that hold it top and bottom to the traveling saw carriage. “You have to know how to cut and how thick to cut, and you have to decide very fast,” he says. He can usually tell what the color and figure will be like before the log opens, he says, but there are always surprises. “You cut one way and you get something, you cut another way and you get entirely something else. You can lose a whole log by wrong cutting. Terribly hard-ball business, saws screaming like a hundred banshees all the time.”

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Stanley Powerlock 16-ft. tape measure

Sketchup Class

Drafting Tools

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in