The earliest architectural application of bevel-edged paneling is found in wide- board wainscot , which covers or actually constructs the interior walls of our oldest houses. When applied to the interior surface of exterior walls, this wainscot was nailed horizontally to the vertical studs or planking which structurally supplemented the posts. Since the braced frame integrated with the chimney mass could support a second story, interior walls were never load-bearing, and in fact were structurally unnecessary. To divide chambers, and to provide a finished surface in both rooms, early house-wrights used wide boards joined at the edges and fastened to floor and ceiling beams. These walls were from 1 in. to 1 % in. thick, the same dimension as the boards.

The conventional to tongue-and-groove joint with the addition of a decorative bead was sometimes used to join such wainscot, but a beveled edge set into a groove on the adjoining panel appears to have been most common. For constant thickness and to make a wall with both surfaces in the same plane, the boards were beveled on both sides, resulting in a decorative feature visible on both sides of the wall. Featheredged paneling is another name for such a wall treatment.

Panels joined by a simple tongue and groove had the undesirable habit of showing shrinkage as the two butted edges pulled apart. Feather-edged panels, having no distinct dividing line when viewed face-on, belied movement with the seasons, an important reason to use this type of joint. The beveled-edge joint was also used to construct interior and exterior plank doors. Wide boards were joined in the aforementioned manner and held together by clinch- nailed battens. Exterior doors were made of double-layered boards, the inside layer being horizontal and clinch-nailed through the vertical exterior layer. Original doors of this type are quite rare, time and weather having taken their toll.

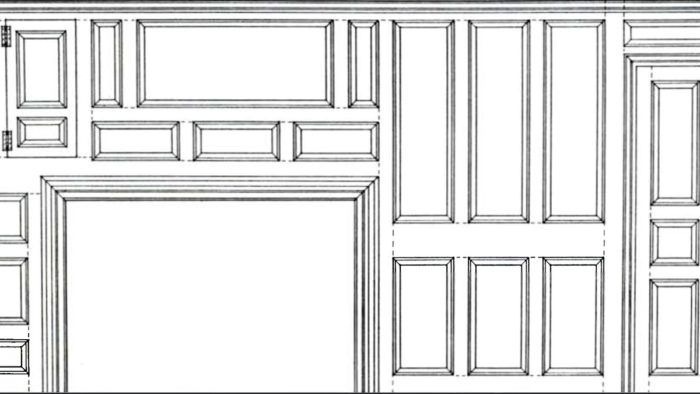

In work dating from late in the 17th century we see many more raised-panel doors. A framework of mortised-and-tenoned rails and stiles formed the structure that housed the panels, which were beveled like the feather-edged boards. A groove was plowed into the framework ‘s interior edges, into which the panels were fitted. On feather-edged boards a bevel was planed only upon edges running with the grain, whereas for raised panels, a bevel was also cut across the grain on the top and bottom edges. Many of the earliest doors had two wide panels, one above the other divided by a center rail. Later, four panels, two above two, became most common. The grain of the door panels always ran vertically, and the outside stiles, or vertical frame members, extended the full length of the door. Panels were never fastened, and were allowed to expand and contract freely yet invisibly.

On one side of a door, the inside edges of the rails and stiles were often given a decorative molding, mitered at the intersecting corners and forming a frame surrounding the raised panels. This treatment became the rule for most doors, despite the complications it caused in the making of the joints. Some doors were molded on both sides, but these are as scarce as they would have been difficult to make.

From Fine Woodworking #18

From Fine Woodworking #18

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in