Making the Rule Joint

With hand tools, the process is as important as the product

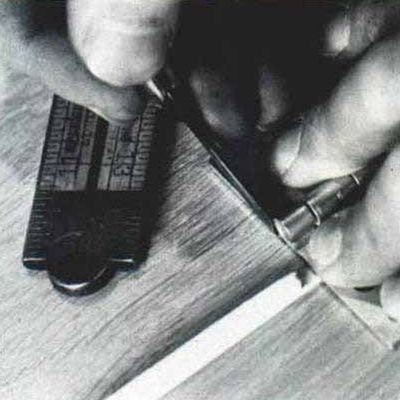

Synopsis: Alasdair G.B. Wallace shares his detailed philosophy of the virtues of working with hand tools over the expedience of machines, and then he explains how he made a Jacobean double-drop-leaf table using rule joints between the tabletop and the leaves. It’s an aesthetic and strong joint — downward pressure on the open leaf is transmitted to the central tabletop, effectively tightening the joint rather than relying on the hinge and screws. He explains each step in making the table, and photos illustrate as he performs the tasks.

While inspecting repairs being made to the roof of his village church, the vicar was puzzled to see that an old woodcarver was putting the finishing touches to an elaborately carved angel’s face. To the question of why such beauty should be located where nobody would ever see it, the craftsman replied that both he and God knew it was there. I recently was reminded of this story when a customer requested that I sign a butternut chest I had made. It occurred to me that whatever task we undertake, the finished product is in itself the quintessence of the craftman’s signature.

In this age of mass production, personal signature has become the exception rather than the rule. The development and improvement of the tools of mass production have lessened the need for skills. Haste has become our byword, convenience our creed. The product has become more important than the process, and in the transition, something of inestimable value has been lost.

Unlike steel or plastic, no two pieces of wood are identical. Species, age, moisture content, cut, grain configuration, knot placement all contribute to the character of each piece and demand individual treatment. The proliferation of plywoods, chipboard and cheap veneers and the abhorrence of faults, knots and unusual grain pattern by those involved in mass production have almost obscured the diversity and beauty of this warm, venerable and versatile medium.

At Rendcomb College in England, my passion for manual processes stemmed from necessity. There were no power tools. A visionary headmaster, when questioned by a student about purchasing a table saw for the workshop, replied that ripping by hand was good for the soul. I still remember many hours of pumping a treadle lathe and hand-planing 3/4-in. oak for 1/4-in. panels. The sense of pride and accomplishment in the finished product was directly related to the time and effort expended in completing the task.

I continue in the manual tradition today because for me the process continues to be of greater importance than the product. Today’s machinist will argue that leaving no traces of the saw, planer and shaper attests to his mastery of the tools and the care with which they were programmed. This is true. But machines, whether television or router, destroy the sensations of wonder, joy and accomplishment. The table saw’s wail, the sander’s whine, the router’s scream deny a subtler, finer music and remove the woodworker from the personality of his medium. To submit to the machine denies the sensuous process so essential to the woodshop, and the work shows no trace of the craftsman, his tools, his labor. Wood is not homogeneous. Why then use a machine that by its very nature seeks to create a uniform product? Beauty lies in diversity, not uniformity. Hear the varying song of the plane as it skims oak, walnut or pine, the crunch of the chisel’s edge cutting to the dovetail’s line. Savor the perfumes of the crosscut in cherry, maple and elm.

From Fine Woodworking #18

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Stanley Powerlock 16-ft. tape measure

Bessey K-Body Parallel-Jaw Clamp

Veritas Standard Wheel Marking Gauge

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in