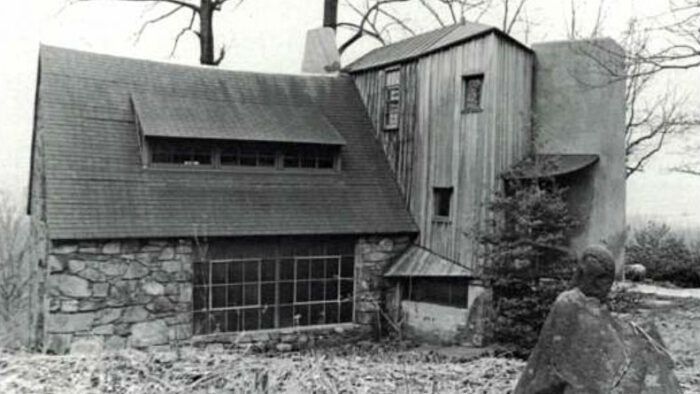

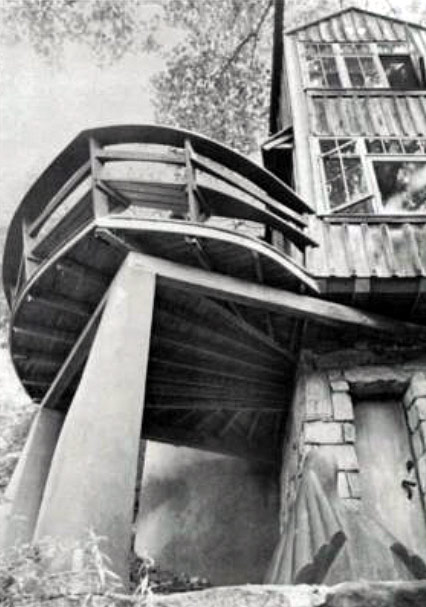

On a wooded Pennsylvania hillside during the 1920s, Wharton Esherick began creating furniture that challenged the symmetry and straight lines dominating the traditional woodworking of the times. Many of his designs were inspired by the forms he saw in living things, especially in the trees surrounding his studio. His friend, the late Philadelphia architect Louis Kahn, once said, “Trees were the very life of Wharton. I never knew a man so involved with trees. He had a love affair with them; a sense of oneness with the wood itself…”

Esherick’s application of organic design to furniture making has since become the trend in contemporary woodworking, but few of today’ s craftsmen realize that Esherick was creating “modern” furniture over a generation ago, or that his work helped to free them from the restrictions of previous styles. Most of Esherick’s influence is hidden, subconsciously passed from teachers who knew him and visited his studio to their students. Today, pieces that are reminiscent of Esherick’s style frequently appear, though their designers may not even know about Esherick’s work.

Many teachers and craftsmen working today do, however, acknowledge Esherick’s influence. Arthur (Espenet) Carpenter of Bolinas, Calif., a craftsman noted for his graceful organic style, has said, “Esherick’s sculptural treatment of wood, independence of working and the timing of his life make him the 20th-century progenitor of the present furniture craft. ” But Esherick’s influence was not merely stylistic it was also an invitation to younger craftsmen to join him in creating pieces of furniture that were also works of art. The versatile craftsman and teacher Wendell Castle of Scottsville, N.Y., revealed what he had learned from Esherick’s work: “Esherick taught me that the making of furniture could be a form of sculpture; Esherick caused me to come to appreciate inherent tree characteristics in the utilization of wood; and finally he demonstrated the importance of the entire sculptural environment.”

Esherick himself believed teachers inhibit the growth of developing artists and he urged students to develop their own style. He dismissed offers to teach by saying, “I make, I don’t teach.” However, he did open his studio to students and loved to discuss his work with them. Today, his pieces are now in the permanent collections of several major museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, and the Addison Gallery of American Art in Andover, Mass.

From Fine Woodworking #19

From Fine Woodworking #19

To view the entire article, please click the View PDF button below:

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in