In Search of Period Furniture Makers

What they do about what the 'old guys' did

About a year ago we received a letter from a reader, Grover n W. Floyd II of Knoxville, Tenn., telling about the cabinetmaker with whom he had been studying, whom he believed to be “among the nation’s finest.” The letter included a newspaper clipping about Robert G. Emmett, 77 , quoting him as having promised himself, “If I ever got to touch a piece of Goddard furniture, I never would wash my hands. But now I have seen the back of a genuine Goddard piece and its drawers. And I wash my hands. My construction is better.”

It wasn’t long before I had arranged a trip to Knoxville to meet Emmett and to see his furniture. The visit turned out to be the start of an odyssey — to the back rooms of museums, to historic sites and to the shops of reproduction cabinetmakers, all to gain a perspective on what Emmett was to show me. Here he was declaring his furniture construction to be better than that of 18th-century master craftsmen, to be “second to none in the world.”

I met Floyd first, a 29-year-old Scotsman who works out of a 500-sq. ft. shop, modestly equipped with the basic machines, all kept in faultless tune. When I arrived he was at the table saw, stacking and slicing arrowhead inlay banding in. thick, practicing a technique he had learned from Emmett. He showed me a number of simple blanket chests, identical in design but of different sizes — experiments in proportion. Floyd is a professional cabinetmaker who earns his living restoring and building traditional furniture. But since he met Emmett, he’s considered himself a student. He brought me to meet the teacher.

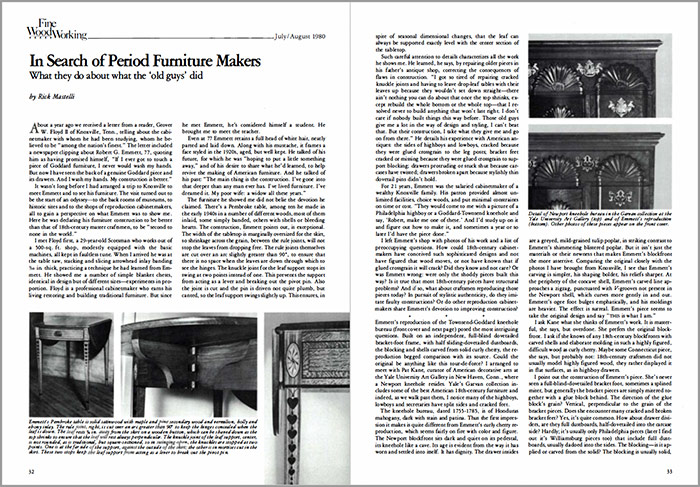

Even at 77 Emmett retains a full head of white hair, neatly parted and laid down. Along with his mustache, it frames a face styled in the 1920s, aged, but well kept. He talked of his future, for which he was “hoping to put a little something away,” and of his desire to share what he’d learned, to help revive the making of American furniture. And he talked of his past: “The main thing is the construction. I’ve gone into that deeper than any man ever has. I’ve lived furniture. I’ve dreamed it. My poor wife: a widow all these years.”

The furniture he showed me did not belie the devotion he claimed. There’s a Pembroke table, among ten he made in the early 1940s in a number of different woods, most of them inlaid, some simply banded, others with shells or bleeding hearts. The construction, Emmett points out, is exceptional. The width of the tabletop is marginally oversized for the skirt, so shrinkage across the grain, between the rule joints, will not stop the leaves from dropping free. The rule joints themselves are cut over an arc slightly greater than 90°, to ensure that there is no space when the leaves are down through which to see the hinges. The knuckle joint for the leaf support stops its swing at two points instead of one. This prevents the support from acting as a lever and breaking out the pivot pin. Also the joint is cut and the pin is driven not quite plumb, but canted, so the leaf support swings slightly up. This ensures, in spite of seasonal dimensional changes, that the leaf can always be supported exactly level with the center section of the tabletop.

From Fine Woodworking #23

From Fine Woodworking #23

To view the entire article, please click the View PDF button below:

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in