The Frame and Panel

Ancient system still offers infinite possibilities

Synopsis: Few systems in the range of woodworking have more variation and broader application than the frame and panel. It’s a basic unit of structure, and it can be varied almost without limit. In this article, Ian J. Kirby explains its movement and tells you how to overcome the panel’s tendency to distort. He examines differences between raising and fielding, inlaying and carving panels, options for designing the frame and for the panel, how to cut the bevel, and how to minimize errors.

From Fine Woodworking #23

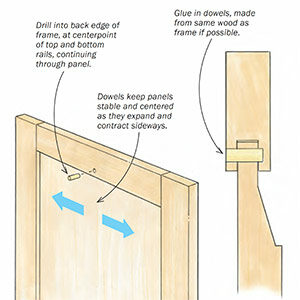

Scarcely another system in the whole range of woodworking has more variation and broader application than the frame and panel. In the frame-and-panel system, pieces of solid wood are joined together into a structure whose overall dimensions do not change. The frame is usually rectangular, mortised and tenoned together, with a groove cut into its inside edge. The panel fits into this groove: tightly on its ends since wood does not move much in length, but with room to spare on the sides because wood moves most in width (figure 1). Wood is not uniform and as it moves in response to changing moisture conditions, it cups, twists, springs and bows. Trapping the panel in the groove inhibits this misbehavior.

Historically, the basic technique that made possible the frame and panel is the mortise-and-tenon joint, on which I have already written extensively. The frame and panel is a basic unit of structure. It can be used singly (a cabinet door) or in combination (to make walls, entry doors, cabinets). The several elements of a single frame and panel may be varied almost without limit, and its aesthetic possibilities are infinite. The little choices made during its manufacture are aesthetic choices, and we can begin to see the interdependence of design and technique. Neither the frame-and-panel system nor its joinery can be thought of as an end in itself. Neither has any importance except in application, toward the end of making a whole thing out of wood.

To overcome the panel’s tendency to distort, we make it as thin as the job will allow, while we make the frame relatively thick. By doing this we haven’t significantly altered the amount by which the panel will shrink and expand, but we have rendered it weaker so that the frame has a better chance of holding it flat. Panels can be made as thin as 3/16 in. but such panels were uncommon before the 19th century because woodworking tools were not readily capable of such refinement. The thickness of the panel was dealt with in a number of ways, the most usual being to raise and field it.

Generally raising and fielding are thought to be the same thing—the process of cutting a shoulder and a bevel on the edges of the panel and thereby elevating the field—that is, the central surface of the panel. I’d like to distinguish between these two terms. Fielding refers to any method of delineating the field of the panel from the frame; raising means cutting a vertical shoulder around the field, which may or may not be accompanied by a bevel.

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Starrett 12-in. combination square

Festool DF 500 Q-Set Domino Joiner

Bessey EKH Trigger Clamps

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in