Synopsis: Toshio Odate describes his early training as an apprentice in Japan and the painful, but lasting, lessons he learned there. Then he describes Japanese blades, how they are made and reconditioned, and how to sharpen them with waterstones. He explains how to maintain the flat back and prepare the plane. Photos show his technique of sharpening while on the floor, among other techniques.

Although most woodworking apprentices begin training at the age of 13 or 14 years, I was 16 when my parents decided I should apprentice to a tategu-shi, the craftsman who makes doors, shoji (screens) and room-dividing panels. My starting master was my stepfather, which was unusual. It was common to be sent to apprentice with another craftsman for at least the first two to three years for spiritual as well as technical training. My stepfather was very strict and believed a father could not teach his own son. The first day he said to me, “From this day on we are total strangers. I will treat you like a common apprentice, maybe harder. You should call me master, not father.” He did as he said.

A tategu-shi apprenticeship lasts five years. Two additional years, the first and last, are done as a service to the master, extending the relationship to seven years. The first year is spent working in the household and studio doing errands and assisting the master’s wife. At this time you are beginning to learn the manners and attitudes of a craftsman through observation. The seventh year is spent working as a craftsman without salary to show appreciation to your master.

An experience in my third year that is still important to me helps to illustrate the relationship a craftsman has with his tools. I had saved a little pocket money given to me by my master and other craftsmen for doing errands. But as my daily needs were taken care of by the master, there was little reason to have or spend money. On the first and fifteenth day of the month we would take a half day off, but only after the master’s tools and my tools were taken care of and the shop was cleaned. I was finally free around two o’clock. You can imagine just how precious those hours were to me. One afternoon I took the train to a store that was well known for its fine tools. There I purchased a plane that had been made by a famous blacksmith. At the time I did not know his name or the fine quality of his tools. All I knew was that the plane was expensive. On the train I was so overjoyed I unwrapped the plane and held and looked at it all the way home. I knew I couldn’t show the plane to anyone because people would laugh at me — I was still a novice. I couldn’t even keep it in my toolbox for fear someone would see it. I enjoyed the plane every evening while in my room. After the lights were turned out, I kept the plane by my bedside.

One day it was raining, and everyone was fixing tools. I don’t remember why—it wasn’t a day off—but my plane was now in my toolbox. I was pretending to fix my tools but was really looking at my plane. All of a sudden my master was standing behind me. It was too late. He asked, and I had to tell him I had bought it. He took the plane and showed it to the other craftsmen. They, too, thought it was a wonderful tool but teased me because I still did not know how to appreciate its greatness. They took the blade out of the block and examined it carefully. They talked about it for a long time, then gave it back to my master. My master came to me holding the plane in his hand and told me simply that the plane was too good for me. He took it away, and I never saw it again. I had expected that to happen.

Tools are made to be used, and great tools have to be used by great craftsmen. The plane was not for me and should not have been mine only to keep in a cabinet. I should have had greater respect for the tool and the craftsman who made it. It was a very painful and expensive lesson, but I learned.

Sharpening Japanese blades

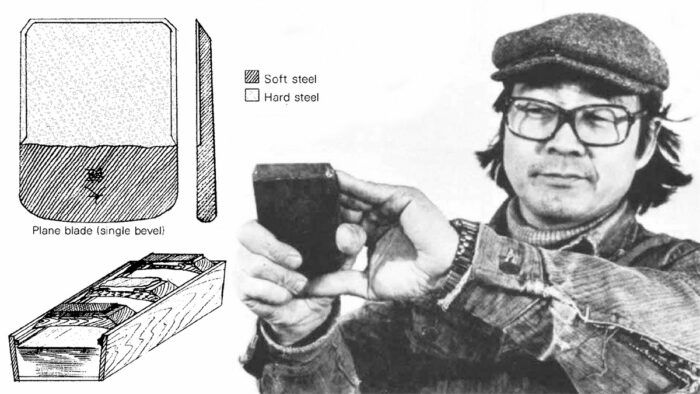

Most Japanese woodworking tool blades are made by laminating steel. High-quality Western blades also used to be made this way. The edge of the blade is thin and extremely hard and is supported by a thick, soft steel. The center of the back of the blade is hollowed-out to facilitate keeping the back completely flat. Most blades are beveled on one side, except for ax-like tools, which are beveled on both sides with hard steel laminated in the center. Plane blades, chisels and knives are made in the same manner, and the methods for sharpening them are similar. Once you have learned the techniques of sharpening plane blades, which are the most complicated, you will be able to sharpen any flat blade.

A new plane is usually ready to use, but most Japanese craftsmen will recondition it to suit their own preference. The optimal bevel angle depends on the quality of the blade and on the kind of work you are doing. Until you know otherwise, it is best to maintain the original bevel angle of the blade. If the edge of the blade is not finished when purchased or is badly chipped, a grinder can be used to start the sharpening process. When I worked in Japan I did not have a grinder and always used a coarse stone, as was the custom. Mechanical tools were generally not used. Today a wide variety of machines and tools is available to make dressing or redressing a blade faster and more accurate, but sharpening itself, honing the final edge, has to be done by hand.

There are oilstones and there are waterstones; in Japan we used only waterstones. Many Japanese craftsmen prefer natural stone, but it is difficult to find large stones that have an even consistency. Today, manufactured stones are readily available at an affordable price. Three stones (coarse, medium and fine) are needed. When sharpening (and not redressing) a blade, only the medium and finishing stones are used.

When using a waterstone, water must be added constantly, or the pores of the stone will clog. Keeping the surface of the stone clean gives a faster grind. Japanese craftsmen keep a bucket of water next to the stone, or they have a sink-like wooden box beneath the stone.

In sharpening, be sure to wipe the blade before changing to a finer grade stone to keep from transferring coarse particles. Before changing stones you should allow the stone you’re on to dry during the last few strokes. This results in a smooth transition to the next stone. As the stone dries, the pores of the stone clog slightly, thus acting as an intermediate grit.

How the blade is held during sharpening is important. The plane blade is held in the palm of the right hand with the index finger extended. Place the first two or three fingers (depending upon the size of the blade) of your left hand in the space created by the right thumb and index finger. Your fingers will maintain pressure on the blade so as to steady the bevel. The left thumb, placed under the blade, will provide support for the back.

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Olfa Knife

Honing Compound

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in