Synopsis: This excerpt from George Nakashima’s book The Soul of a Tree illustrates and discusses Nakashima’s relationship to his material and how his furniture evolves in the subjective organic sense. He’s concerned with the active process of bringing objects into being, not for the sake of what they become at the end of it all, but for the sake of the work itself. As he writes, every tree, every part of each tree, has only one perfect use. His creative vision conjures opportunities lost in ages past and how to realize the potential of great timber before you today.

From Fine Woodworking #32

When trees mature, it is fair and moral that they are cut for man’s use, as they would soon decay and return to the earth. Trees have a yearning to live again, perhaps to provide the beauty, strength and utility to serve man, even to become an object of great artistic worth.

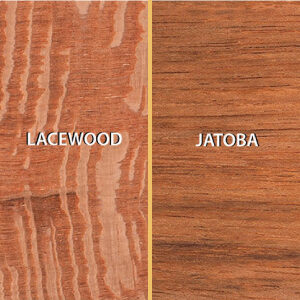

Each tree, every part of each tree, has only one perfect use. The long, taut grains of the true cypress, so well adapted to the making of elegant thin grilles, the joyous dance of the figuring in certain species, the richness of graining where two large branches reach out—these can all be released and fulfilled in a worthy object for man’s use.

How to acquire logs and what to do with them calls for creative skill. There is so much that is wasted and unrealized. Consider the great timbers, some ten feet in diameter, piled across slopes and gulleys to make railroad beds in the early days of this country. Or the magnificent zebrawood log, from which boards fully four feet wide and eight feet long could be cut, but which instead is cut into pieces 3/8-in. thick, six inches wide! What a waste of a majestic opportunity! This is the psychology of match-stick manufacture. And the tragedy of once-in-a-lifetime timbers cut into veneers so thin the light can shine through. What a waste, simply for money!

Logs from all over the world make their way to my storehouse. Some are of great value, some quite inexpensive but with interesting possibilities. There is need always to select and to search, even to look underground where the most fantastic grains can often be found.

Each species of tree has its own characteristics. Extremely long fibers and resistance to rot are characteristics of the cedar, the cypress, and, in a way, the spruces and hemlocks, the firs, and the other evergreen trees. These characteristics are important where tautness and resistance to weather are necessary. The woods from these trees often have beautiful, very straight graining and are useful in architecture for grilles like the starburst asa-no-ha, and even musical instruments. One of the finest perhaps is the Japanese cypress, and not far behind are the Port Orford cedar and the Alaska cedar, neither of which is a true cedar at all, but a cypress.

The European walnut, whether from Kashmir, the area around the Caspian Sea, southern Russia, northern Iran or eastern Turkey, or from western Europe, is among the finest of furniture woods, and one I use with frequency. American walnut, a different species, is also greatly admired, especially by Europeans at this time.

Cherry and other fruitwoods produce material of great quality. Black persimmon, often considered the finest of Japanese woods, is now extremely rare.

All woods have graining—patterns created by the trunk fibers. However, the grain of many woods, pine and maple for instance, is regular and comparatively uninteresting, while that of walnut, cherry and other fruitwoods is intricate and exciting.

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Ridgid R4331 Planer

AnchorSeal Log and Lumber End-Grain Sealer

DeWalt 735X Planer

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in