Last summer, amid the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina, I attended a week-long chairmaking workshop that changed my ideas about working wood. Ten of us had come because we were interested in learning to make chairs in an old way. We put aside our electric tools and surfacing machines, and we kicked the habit of using mill-sawn, kiln-dried wood. We retreated from the cabinetmaker’s craft, with its jointing and smoothing planes and sandpaper. Instead, we adopted the tools of the country joiner, who rives the wood and shaves it into sticks and panels.

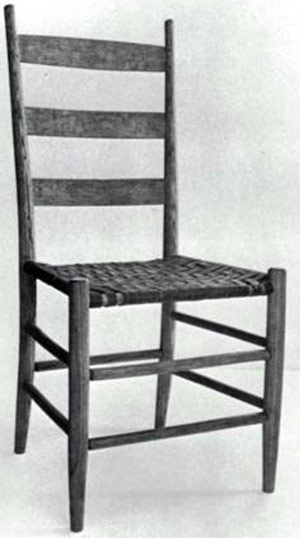

The joiner’s craft has been practiced for centuries in peasant communities, where everyone, for at least part of the year, produces food, shelter, clothing, utensils, and furniture. Originally a homely craft, it evolved into a specialized profession, which in parts of this country is being revived as part of the modern-day homesteader’s diversified livelihood. The country joiner does not employ a sawmill, but goes directly to the local tree and, treating wood like the bundle of fibers that it is, pries it apart with wedges, gluts and froes. He shapes this riven wood with drawknives and spokeshaves, retaining the continuity of the fibers that a rip saw would sever. Riven wood is stronger than sawn wood, easy to work while green, and more resistant to the deterioration of age and weather. Its grain and figure can be felt, not just seen as in planed and sanded wood. Its texture is rich and varied. And when you rive and shave wood, there is no dusty air to breathe. Green woodworking relies upon simple tools, cheap materials and direct processes. The result can be as useful, beautiful and inspiring to make as the chair pictured here.

Our classroom was an old tobacco barn on Drew and Louise Langsner’s 100-acre homestead in Marshall, N.C. To get there, you drive along increasingly rural roads, till the last half-mile or so of the Langsner’s driveway, which is best walked. “When you come to Country Workshops,” remarked Langsner as his truck bounced us up to within reach of the farm, “you come to the country.” Each summer, the Langsners sponsor as many as five week-long workshops in country crafts, alternating their workshop responsibilities with their farm chores. We helped a little with those chores, ate three bountiful meals a day of farm produce, and slept in our own tents. We worked long days and into the night, not exploring our individual bents, but practicing craft in the age-old sense. We did not design, for instance, but copied a traditional design. And though we initialed the parts we made, we didn’t take the identification too seriously—on the first day we shaved more than a hundred rungs and threw them into a communal pile. In this way we concentrated on acquiring skills and minimized prideful fussing, making extra parts when we were finished with our own, and sharing them readily.

From Fine Woodworking #33

From Fine Woodworking #33

To view the entire article, please click the View PDF button below:

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in