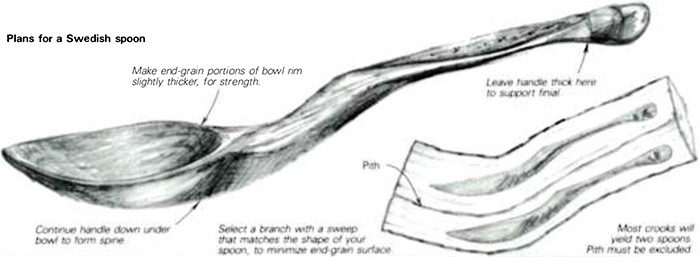

Winter nights are long in Sweden. When farmers go into the forest to cut the year’s firewood, they make a point of also collecting bent limbs and crotches, blanks from which to whittle spoons in the evening months. In rural Sweden many men still wear knives, not as weapons but as ready tools, and it is part of the ritual of conversation to punctuate a sentence with a shaving from a stick. In some parts of the world whittlers carve figures or ornaments, and there are always some who juSt make chips. In Sweden spoons are traditional, and still popular. The centuries have yielded a deep understanding of hand-tool techniques, as well as of the form of the wooden spoon — together they evidence a refined simplicity.

A week-long workshop I attended last summer focused on these hand-tool techniques. The place was Country Workshops in Marshall, N.C. , and the teacher was Wille Sundqvist, a wiry, 57-year-old Swede whose relationship to craft is long and thorough. As a boy he learned to carve by watching his father and grandfather, both of them farmers and winter woodworkers. When he was six years old, he discovered the first principle of knife work while squabbling with his brother. His brother grabbed the knife’s handle and he gripped the blade, and when they pulled, he learned indelibly how knives slice. At 20 Sundqvist hurt his back in a forest accident, and so had to find a career other than farming. He went to woodworking school, where he apprenticed with the illustrious furniture designer Carl Malmsten. Later he taught woodworking at Malmsten’s school, and in various elementary and preschool programs, then for ten years he taught others to be woodworking teachers. Since 1969 Sundqvist has been consultant to the Handcraft Society in the province of Vasterbotten, researching traditional handcrafts and helping the disabled and the elderly become productive craft workers.

Click on “View PDF” to download the full article:

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in