Synopsis: Wash Adams, Doug Polette, and John Leeke discuss repairing and making your own bandsaw blades. They say you don’t need welding equipment, either, just a propane torch and silver solder. Making your own from bulk rolls allows you to choose from a variety of widths and teeth, some of which aren’t generally available in made-up blades. The authors explain why blades break and where to find your parts to fix blades, and how to avoid making the metal too brittle. Side information by Robert Meadow covers making a bandsaw-blade sharpening jig, and an article by Rich Preiss discusses Japanese bandsaws.

From Fine Woodworking #40

You don’t need welding equipment to braze narrow bandsaw blades. A propane torch can generate enough heat, and silver solder is strong enough for a good joint. Any small shop can deal with the nuisance of a broken blade by repairing it on the spot. And if bandsawing is a daily operation in your shop, you can save money by buying blades in bulk rolls. This also lets you choose from a variety of widths and teeth, some of which aren’t generally available in made-up blades. One commercial supplier, DoAll, sells a skip-tooth, -in. blade in 100-ft. rolls. Cut and soldered, each blade ends up costing about $3, and the entire process takes little longer than sharpening and honing a dull tool.

Bandsaw blades break for a variety of reasons. Sometimes a sharp, new blade will snap when you trap it by trying to saw too tight a curve, or when you skew the work. You can repair this type of break successfully, but fixing other kinds of breaks may be a waste of time. A dull blade, for instance, will break if it’s pushed too hard, but repairing, it won’t be worthwhile unless you can sharpen it too. Older blades, even ones that are still sharp, sometimes break because they’ve gotten brittle through work-hardening, having been flexed over the saw’s wheels a few rimes too many. These blades aren’t worth fixing either, because it’s likely that they’ll soon break in another spot.

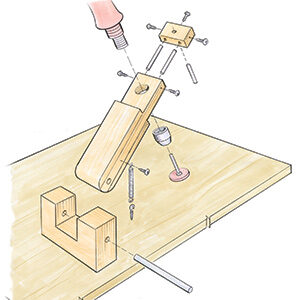

You can probably buy silver solder and a compatible flux at the local hardware store, but be sure that it’s about 45% silver with a melting point near 1100°F, or it will bead up on the blade without flowing. You’ll need to make a holding jig from angle iron or scrap metal to position the ends of the blade while you solder it. The jig can be tucked away when you’re not using it, then clamped in your bench vise when you need it.

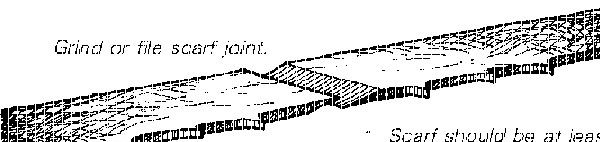

Soldering metal is akin to gluing wood: success depends more on the fit of the parts than on the strength of the bonding material. Attempting to bridge an open joint with solder won’t work. For this reason, the scarf joint should be a perfect fit and carefully aligned. First heat the blade ends red with the torch, then cool them slowly to soften the steel. The surfaces of the scarf should be at least three times as long as the blade is thick.

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Shop Fox W1826

Stanley Powerlock 16-ft. tape measure

Honing Compound

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in