Judy McKie jokingly says that when too many of her pieces are seen too close together, they suggest a menagerie. In the back of her mind, she has a vision of the spacious room each piece will someday occupy. In reality, as far as she knows, people eat breakfast at her breakfast tables and the hall tables gather clutter; daily life becomes part of the designs. In spite of this, or maybe because of it, the furniture is cherished even more.

In her own apartment, with its small, high-ceilinged rooms, McKie’s furniture is crowded by living and use. Her kitchen cabinet has a carved pattern on its splashboard, but it’s completely obscured by canisters and kitchen gear. You can’t get far enough away from her kitchen table to appreciate its carved apron, and the “inlaid” round table in her son’s room is covered with books, papers and fishing tackle. Nothing could better prove that this furniture is functional, fashioned by someone who needed furniture. A legless, boxy chest, made some years ago by McKie’s father in his garage, stands in the hall-absolutely utilitarian, yet it has personality, a pleasing and tolerant character. McKie recalls that when she was a child, her family spent some time winterizing a vacation cabin. Ducking the chore of hanging insulation, 13-year-old Judy spent days sawing out decorative splats for a railing around the sleeping loft.

When she began making furniture 15 years ago, McKie, like many self-taught woodworkers, often did things the hard way. If she had an idea, she had to discover a way to implement it. It seems to me that this is one of her strengths—she could never accept a job as being “right” simply because she had done it the right way. Instead, each piece had to pass on its own merits.

One evening, after maybe seven years of making birch plywood furniture, McKie made an expansive list of everything she could think of that would change the way wood looked. Carving, painting and staining were obvious, but she didn’t exclude the outrageous—crushing, piercing, burning. Once, she loaned her kitchen table to a chain-smoking friend and it came back spotted with cigarette burns. The intense black centers, with their hazy outlines, went on her list of techniques, and later became the SPOtS on the leopard couch.

Her designs remind some people of pre-Columbian art, others of Egyptian work. Animal imagery has always had a powerful, totemic impact on furniture-makers. One observer calls her work a generalized “equatorial art, ” another thinks she touches things that might have haunted a Shaker’s subconscious. The designs are, despite reminding everyone of something else, uniquely her own. Her creatures, instead of representing society’s domination over nature, are a reaching out to nature, a participation in a wild riot of life.

Sometimes her goals are very basic: in her bedroom, squeezed between radiator and doorway, stands one of the homeliest pieces of furniture I’ve ever seen—pine, brown, about a foot wide and seven long, featureless except for a saber-sawn curve between the feet on the side. I asked what sort of proportions she’d been thinking about. “Proportions? It has the proportions that give me the biggest laundry hamper between the radiator and the door, that’s all … no proportions. ” In contrast, against one kitchen wall, there’s an unashamedly elegant dog table, with nothing on it but a pair of brass candlesticks and a fruitbowl. In a home where. even the windowsills are crowded, it’s something of an enigma. “Well, that’s what that kind of table is for, ” McKie says, “that’s its function. It belongs to the whole line of fancy hall tables and sideboards, display pieces. You can’t eat at it, you can’t use it to keep a lot of things on, but there’s always been a tradition for pieces like this. You might not guess it, but I think of my work as classical furniture. This is a classical hall table.”

McKie’s workspace is part of a warehouse-like building that’s a full city-block deep, broken up into good-sized individual areas with a communal lumber pile and centrally located heavy machinery. There’s a spray room, a room for storing finished pieces, and a general air of work being done. The place is more commercial than arty, with piles of kitchen cabinets growing in one spot, architectural components in another.

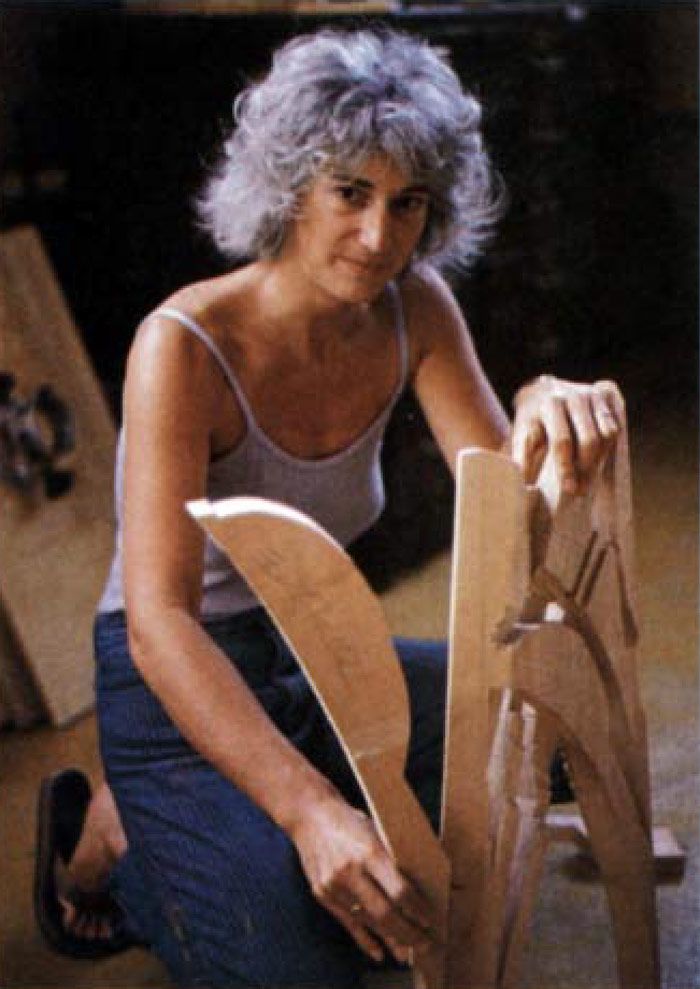

In the shop, McKie works steadily and hard. In the month before her show at Elements, she is finishing up four major pieces at once: lacquering, painting, carving, deciding on fabrics and installing hardware all at the same time. Yet every tool is where it should be, there’s no litter of scraps on the floor. When she goes to mix paint, McKie scoops up the solvent, dry colors, stirstick and mixing cup all in one trip, and her mixing cup turns out to be big enough for the job. To show me an old template, she goes straight to a dark corner and pulls it out. All its parts are labeled, and prudently taped together. In everything, she’s thrifty with effort—she’s been at this for a long time.

Making a living from her work has been, so far, very hard. Entering the big-money art world, becoming an art star, has never been McKie’s intention. She wants to make things that affect her the same way as certain things she’s seen and remembered: objects made with thought and love, showing the concentration and involvement of the maker, utilitarian things that go beyond mere utility, sculptural things that will last in the mind. Yet she still must make a living. If she is to clear $ 10 per hour for her work, the marquetry fish chest will have to sell, including the gallery’S share, for maybe $ 14,000. That allows nothing for all the time spent on all those pieces, stillborn, that haunt the corners of her shop. She has spent a year of her life, and exhausted a $25 ,000 grant, making seven pieces of furniture.

The show at Elements was a success, and will stake her for another year. But McKie is concerned that a gallery’s markup will put her work beyond the reach of the clients who have so far been her main support-her friends, people who love her work as furniture rather than as an investment. Yet, with a good gallery behind her, doing its job, she would never again have to bargain for a fair price, never have to scale down an idea to fit a budget. She always comes out on the short end in such transactions, because the furniture she makes is as much hers forever as it is the person’s who buys it. Whatever the piece, and whatever the price, Judy McKie digs down deep and makes it work.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in