Synopsis: At best, veneer produces superb results; done badly, it’s a mess. In this article, the first in a series, Ian J. Kirby explains what veneer is and talks about varieties of substrates and how to prepare them for veneer. He suggests using fiberboard or particleboard as a substrate to prevent moisture-related movement, and he warns against using plywood. He explains how to cover all substrate surfaces, including how to deal with edges, and which types of glue you should use. A side article talks about different ways to slice veneers and which side is best to use.

Veneering can lead to furniture designs that just aren’t possible with solid wood. Lots of furniture has the shape it does because of wood’s hygroscopic nature—you have to allow wood to expand and contract. Once you master veneering, however, you don’t have that restriction. You can turn particleboard and fiberboard into dimensionally stable panels that are as attractive as any piece of solid wood, opening up a whole new world of design possibilities.

A veneer is simply a thin layer of wood, which can be glued on top of another material. At its best, veneering produces superb results. Done badly, it’s a mess. You must plan every step before you begin. Unlike other woodworking, you don’t start with a large plank and carve it down; you begin with a small piece and build it up to the size you want.

Veneering allows you to use woods that would be too expensive (rosewood or ebony) or just too unstable (burls or crotches) to be worked in solid form. Veneers have been available for centuries, of course, but what has now brought veneer into the small-shop woodworker’s province is the advent of man-made substrates, the material onto which the veneer is glued. Particleboard and medium-density fiberboard have changed the whole nature of veneering.

In this article, the first in a series on veneering, I’ll discuss veneers, substrates and how to prepare them for veneering. Future articles will deal with the application of veneers, and with design considerations when using veneered boards.

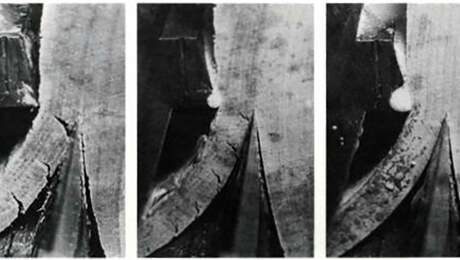

Until the turn of this century, woodworkers had to make their own solid-wood substrates for veneering, and that was a real problem. If you veneer solid wood, laying the grain of the veneer at right angles to the grain of the solid wood, the veneer will come under tremendous stress as the substrate shrinks and expands, and can crack or delaminate. Even if you orient the grain of both materials in the same direction, you’ll just have ordinary wood with a different wood glued onto it—with all of solid wood’s moisture-related problems.

The traditional solution was to make large panels out of many small panels within frames, the assumption being that each little panel would shrink and expand less than one large panel would. It seems to have solved the problem in many cases, yet it shouldn’t. Lots of little bits of wood will expand and contract collectively as much as one big piece of wood.

Today you can sidestep all of these problems by using particleboard or fiberboard as the substrate. These materials are so stable that seasonal movement is negligible. Probably the best substrate is medium-density fiberboard (MDF). It is made by breaking down wood into its fibrous form, then pressing the fibers back together again with an adhesive.

From Fine Woodworking #46

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Bahco 6-Inch Card Scraper

Whiteside 9500 Solid Brass Router Inlay Router Bit Set

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in