Synopsis: You don’t have to be a botanist to distinguish oak from ash, though many antique dealers miss the distinctions between them. Jon Arno explains their different grain patterns, acid properties, working characteristics, price, and availability. Along the way, he provides the genus and species information and tells you where each grows best.

At a recent antiques show, I found a dozen or so turnof-the-century commodes labeled “oak.” The general public and a lot of antiques dealers seem happy enough to identify every light-colored, open-grained wood as oak at a glance. The oak label serves as a convenience for pricing and dating such pieces, but it isn’t always accurate. Two of the commodes at the show were of mixed wood construction (predominantly elm); the three nicest were unquestionably ash.

Most people may not have much reason to care. Ash and oak are both open-grained woods, with similarly attractive and somewhat racy figures. Furniture made from either wood has a look of solid quality. Yet I think ash outclasses oak in several important ways, at least from a cabinetmaker’s viewpoint—the two woods have decidedly different characteristics. For starters, oak is a member of the beech family, Fagaceae, which includes the oaks, the beeches and the chestnuts. Ash belongs to the olive family, Oleaceae, and is related to lilac and forsythia.

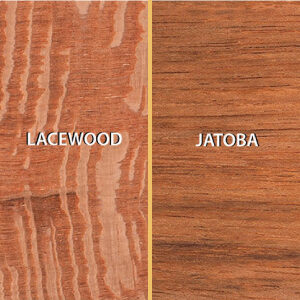

You don’t have to be a botanist to quickly separate oak from ash. Oak has prominent rays that are easily visible on the flatsawn surface, where they appear as bold lines called ray flecks. In some species of white oak, these flecks may be more than in. wide and well over 1 in. long, while in the red oaks they are generally smaller and darker. In fact, the rays are such a dominant feature in white oak that it’s often specially quartersawn to expose them as broad bands or ribbons. These are extremely hard and dense, and in stained wood you could call their appearance either fantastic or outrageous, depending on your taste. I personally don’t like the effect, but if you do, score one point for oak, because no matter how you cut ash, it will not produce this pattern. Like all woods, ash has rays, but they are almost undetectable with the naked eye. As a cabinetmaker, I view this as one of ash’s great virtues, because flatsawn and radially sawn boards can be used in the same piece with no surprises when the stain goes on.

Oak contains tannic acid. If you expose the wood to strong ammonia vapor, a chemical reaction will turn it dark brown. This staining process is known as fuming, and it won’t work on ash. Personally, I use ammonia only on windows, but if fuming sounds like a good idea to you, score another point for oak.

Oak’s acid content is a mixed blessing at best. A friend of mine once left a green piece of oak on his tablesaw overnight, and by morning it had permanently etched its shape as a black rust mark, which is still there after four years.

From Fine Woodworking #51

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

AnchorSeal Log and Lumber End-Grain Sealer

DeWalt 735X Planer

Ridgid R4331 Planer

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in