Starting Out: Build and Fit a Basic Drawer

The fourth in a series of articles to help beginning woodworkers get going with the craft

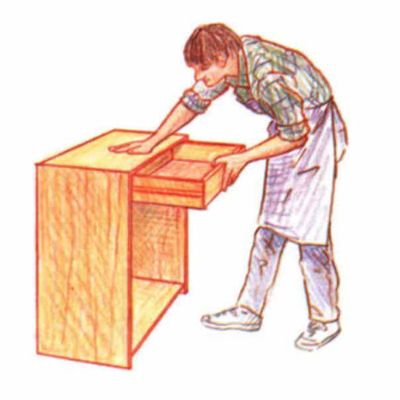

Synopsis: In this, the fourth of a series of articles on starting out, author Roger Holmes discusses how to build and fit a basic drawer. He says that making drawers can be fun, as long as you don’t let your ambition outstrip your ability. The drawer joinery he shows here will allow you to get the hang of making a drawer square and fitting it to a cabinet before you stir dovetails into the mix. He talks about stock preparation, squaring up, grooving the insides of the faces, dadoing the sides, and making locking joints at the front corners. The runners for the drawers are best made of a hard wood, he says, and he explains how to fit the drawer to the carcase. Lots of illustrations complement his explanations.

I have always been fond of cabinets filled with row upon row of little drawers, each cleanly dovetailed and snugly fitted in its opening. Drawers seem full of promise and mystery. When they’re closed, that is; an open drawer usually reveals much more junk than treasure. But there is pleasure in sliding open a well-made and well-fitted drawer, even if it’s filled with shoelaces and paper clips.

Making drawers can be fun, too, if you don’t let your ambition outstrip your ability. I’ll never forget the sight of my first attempt, a little drawer barely three inches deep, buried beneath a network of pipe clamps attached in a vain attempt to pull its ill-fitting dovetails tight and its corners square. The drawer joinery shown here is more modest, but perfectly adequate. Using it will allow you to get the hang of making a drawer square and fitting it to a cabinet before you stir dovetails into the mix. And if you need lots of drawers, these are quick to make. Drawers are also well suited for mass production—if you’re making more than one, do the same operation on all the pieces at the same time.

The fit of a drawer in a cabinet can be as important as the construction of the drawer itself. I always make the carcase first and then the drawers to fit it. The ideal is a snug fit, with drawer sides and carcase sides sliding against each other like the walls of a piston and its cylinder (well, as much like a piston and cylinder as your patience and the material allow). But the drawer will work even if it is looser, so fitting a drawer really well is a challenge more than a necessity—a distinction worth remembering after you’ve fiddled around for an unsuccessful hour trying to do it. I use the method described below when I’m trying for that ideal fit; for a less refined and much quicker method, see the box on p. 62.

The drawer joinery—locking tongue-and groove at the front corners, dadoes for the back and sides—is a variation on the carcase joinery described in the last “Starting Out” article. I’ve hung the drawer on runners housed in its sides, which is less traditional than resting the drawer on a frame (a rail under the drawer front, runners under the sides). Frames can stiffen a carcase, and I use at least one or two in tall stacks of wide drawers. Side-hanging the drawers saves time (no frames to make) as well as the space taken up by the frames, which can be as much as 3 in. on a four-drawer cabinet. The method below, however, can be used to fit either type of drawer.

From Fine Woodworking #51

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Grout float

Stanley Powerlock 16-ft. tape measure

Starrett 12-in. combination square

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in