Synopsis: John Hines took a class from Wayne Barton on chip carving, or kerbschnitzen, which describes a style of carving that uses a short-bladed knife to cut intricate designs. The key, Barton says, is learning to hold the knife in an unvarying, cocked-wrist position, ensuring a consistent 65-degree cutting angle and clean cuts. All the tools needed are two Swiss-style knives, and a pencil, compass, metric ruler, and eraser. Photos and detailed drawings show how to cut pyramids, rosettes, and other forms. Hines says it may be the only technique in the woodworker’s repertoire that a machine can’t duplicate. Barton writes a secondary article on how to sharpen chip-carving knives.

It never occurred to me that I could become seriously interested in chip carving—a skill I always associated with primitive folk objects covered with rows of incised squares and triangles repeated in boring symmetry. Then I saw Wayne Barton’s work. It was so crisp and lively that it seemed to leap off the table as I walked by his exhibit at a woodworkers’ show in San Francisco two years ago.

Like beautiful music, the elements of his carvings flow smoothly without breaks from one segment to the next, often creating stunning curvilinear forms. Even though the pattern of each carving is generally geometrical and symmetrical, the cuts— because they are so perfectly executed—have the boldness of a Picasso stroke. And, like all true artistry, his work gives the impression of effortlessness.

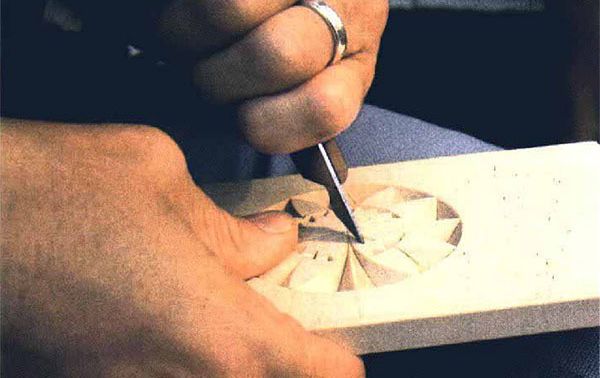

Surprisingly, Barton uses only one short-bladed knife to cut nearly all of his intricate designs, most of which are incised on the lids and sides of jewelry boxes. The designs are based on series of pyramids, triangles, many of them elongated, and gracefully flowing sweeps. Each facet of the design is created by making two or more converging knife cuts into the wood and popping out a chip. No matter how intricate the design, Barton cuts each wall of the facets with a single stroke. No trial cuts. No clean-up cuts. Just one bold incision to sever the wood fibers cleanly from one end of the facet to the other.

Barton, a professional carver who learned his art in Switzerland, says that the key to mastering chip carving, which he calls kerbschnitzen (Swiss for engraving carving), is learning how to hold the knife in an unvarying, cocked-wrist position. This ensures a consistent 65° cutting angle and clean cuts. Then all you have to do is practice until you learn how to make the shallow cuts (seldom more than -in. deep) meet at precisely the same point at the bottom of each facet.

From Fine Woodworking #55

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in