Synopsis: Large tables are wonderful for crowds of feasting relatives, but when they go home, you’re stuck with a conference table for 20, notes Jeremiah de Rham. Expanding tables are the answer, and he explains how extension slides work and how to build a table that uses them. Two beams are sandwiched together so they can slide past each other, held face to face by a coupling system. He uses wooden bearing blocks screwed to the beams as a load-bearing mechanism to support the weight of the table. He discusses design options, and ways to counteract sag. Then he explains how to make them. Side information by Monroe Robinson talks about dovetail slides, and Curtis Erpelding talks about another variation: nesting sliding frames. Extensive drawings and photographs of types of extension tables complete the article.

Large tables are wonderful for crowds of ravenous, feasting relatives. But as soon as they go home, you’re stuck with a conference table for twenty—and who wants to live with that every day? Besides, where do you put such a big table? Expanding tables are the answer to filling the room and feeding the folks three times a year; adding and subtracting table leaves can transform the table into any required size. The backbone of such a useful table is a pair of table-extension slides.

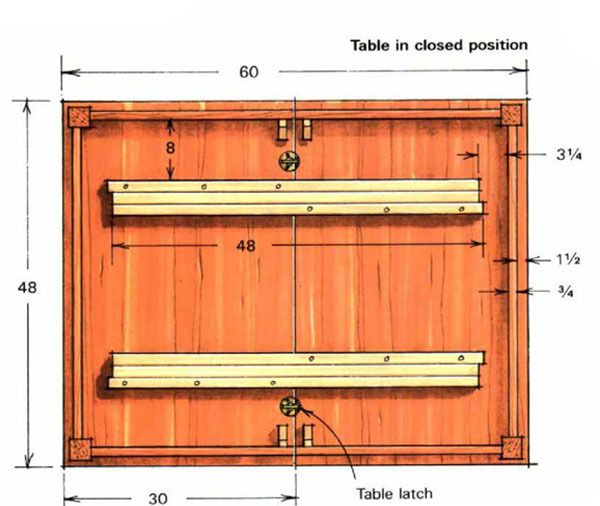

Figure 1 shows the basic way any slide system operates. A single slide consists of two or more beams, sandwiched together so they can slide past each other, and held face-to-face by a coupling system. My coupling system—wooden bearing blocks screwed to the beams—works as a load-bearing mechanism that supports the weight of the table. A slide needs a small amount of play in the coupling system to work smoothly, but this play also creates some sag when the table is extended. The more beams per slide, the more pronounced the sag—especially when the table is in its fully open position. On a smaller table with just two beams per slide, sag is negligible, but a larger table with many beams can sag noticeably. There are three main ways to counteract sag and keep a big table flat: increase beam overlap, crown the slides or add a fifth leg. The table’s design determines which approach to take.

Many four-legged tables are large by design—6 ft. to 8 ft. long when closed—and may not require many additional leaves. This was the case with one table I built. Closed, it measured 7 ft. 6 in. in length. The client required only two leaves, each 10 in. wide. With the table long to begin with and requiring a minimal number of leaves, the slide design was of the simplest variety: two beams per slide stretching the length of the table.

The length of the beams determines how far the table opens. Slides with two 7-ft. beams open a table 6 ft. 4 in.—allowing for an 8-in; beam overlap at the center, which I consider to be the least you can get away with. Shorter beams of 3 ft., centered under the table’s midpoint, will open a table 2 ft. 4 in. (again, with an 8-in. beam overlap).

From Fine Woodworking #65

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Estwing Dead-Blow Mallet

Stanley Powerlock 16-ft. tape measure

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in