Building a Stool

Compound angled joints on drill press and tablesaw

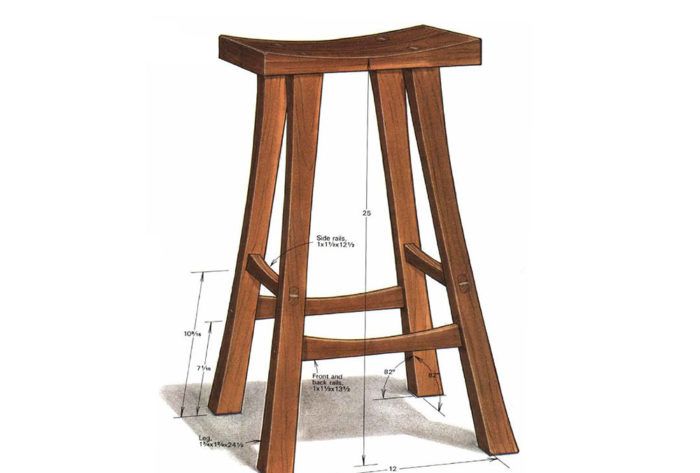

Synopsis: In building this stool, Gary Rogowski he learned that effort, not luck, and planning, not good intentions, are required to build a piece of furniture. In other words, a relaxing weekend of humming and puttering is not enough to concoct a piece with style, grace, and strength. After determining how to solve the stability problem, Rogowski tackled the angled joinery issue. Here, he explains how he did both, how he cut the leg mortises with a drill press, and how he shaped the seat. Side information by Jeremy Singley discusses rung fitting, and a photo gallery of stools accompanies the article.

It was not in the sometimes-a-great-notion category that I decided to build a stool a few years ago. I needed something sturdy to sit on. “How hard could it be to knock out a stool?” I asked myself. My first attempt ended in a three-legged triumph of material over maker. It was astonishingly ugly and so precarious that you could sit on it only with great caution. It did hold a plant very nicely though.

In the process of building my first stool, I learned a basic lesson. Effort, not luck, and planning, not good intentions, are required to successfully build a piece of furniture. This involves a thoughtful approach to design, accurate drawings and careful construction. Gone is the innocent notion that one relaxing weekend of humming and puttering is enough to concoct a piece with style, grace and strength. So, I started over.

Designing a chair or stool is a deceptive task, like setting up a model train. Kind thoughts blessed with the vision of an innocent invariably produce some degree of frustration. It only looks simple. You soon find the job involves more work than you expected. The process is a lot like designing other types of furniture in that it involves solving a series of problems, both aesthetically and structurally. Stools do present unique design difficulties, however. A stool’s parts must strike a delicate balance between looks and weight. Stools look jaunty compared to chairs, are comparatively lighter and easier to move. Yet, looks can’t come at the expense of strength. Thus, a stool is built with the strength of a timberframe house even though its airiness gives the impression it is built of matchsticks.

As if this didn’t present enough of a challenge, recall that, by design, stools are meant to put you high off the floor or close to it. Generally, the former design is more popular because there are more reasons in this world for sitting at workbenches, counters and bars than there are for sitting a few inches off the ground. Thus, stools are generally higher than chairs and narrower in front and side profile. This makes for a weight distribution problem. Chairs are comparatively wider and more stable, so their legs can be perpendicular to or angled from the seat. Stools need all the stability they can get, are more stable and look best if their legs are splayed (i.e. they slope at a compound angle).

From Fine Woodworking #69

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Drafting Tools

Dividers

Comments

You might want to check your measurements. The rails (12.5" and 13.5"?) cant be longer then the distance between the legs at the base of the stool (12"?) as shown.

If you add in the length of the tenons it can.

I love the design but dislike all the jigs and power tools Gary says are necessary. These complicated jigs would be helpful in his production shop to produce multiple stools quickly, but would needlessly complicate the process for a home woodworker who wants to make just a few stools. I would cut all the mortises and tenons by hand - square, not round. I know that either the tenons or the mortises will be angled, but that should not be a problem for someone who has done hand tool work with chisels and a bevel gauge. Those skills are needed for chair making and this is a great project to practice on.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in