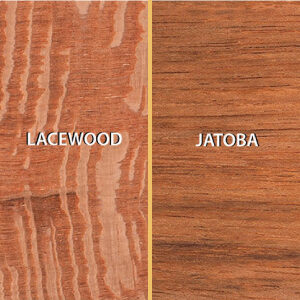

Synopsis: Woodworker and wood technologist Jon Arno says wood identification is becoming increasingly difficult in today’s complex and global lumber trade. The identity of even common domestic species is easily lost between stump and lumberyard. Density, color, texture, figure, and even smell, help to identify wood, but mistakes are inevitable because almost every wood has a look-alike. He recommends a few reference books, a $10 hand lens, and a well-honed pocketknife. Under magnification, anatomical structure will reveal the wood’s unique signature. He explains how to use these tools and shows, using photographs, woods’ different cellular structure, distinguishing hardwoods from softwoods, and then the most important cabinetwoods.

Wood identification is becoming increasingly difficult in today’s complex and global lumber trade. Foreign species are especially troublesome, but with the popularity of terms such as “white woods,” “spruce-pine-fir (S-P-F)” and “mixed hardwoods,” the identity of even common domestic species is easily lost between stump and lumberyard.

Most woodworkers can identify a variety of woods by eye or by a combination of features, such as density, color, figure and even smell. But mistakes are inevitable, because almost every wood has a look-alike. However, the woodworker who really wants to identify domestic and exotic cabinetwoods can do so most of the time. For less than $100, you can purchase the needed reference books (see references, p. 79). The only other requirements are a $10 hand lens and a well-honed pocketknife. Although many woods are deceptively similar in outward appearance, under magnification, each species’ anatomical structure, especially on the endgrain, will reveal the wood’s unique signature or “fingerprint.”

This system is not foolproof: Sometimes microscopic examination of individual cells, chemical analysis, ultraviolet tests and years of training are needed to identify a species. In some cases, not even the most advanced technology can prevail. For example, several species are sold as “white oak,” and science, as of yet, has no foolproof way of distinguishing these by examining the wood alone. Nonetheless, it’s surprising how far a woodworker can get with just a hand lens and some reference material.

Any lens with a reasonably broad field of view and at least 10x power will do. I prefer a jeweler’s loupe with a wide-angle 10x lens at one end and a higher-power 15x lens at the other. The 10x lens will bring into focus the full width of at least one annual growth increment (the wood between two annual rings), which allows for a quick appraisal of the pore patterns. The 15x lens can then be used to study finer details.

It’s necessary to have an absolutely smooth-cut surface on the endgrain of the sample or the features will be blurred. The cut should span at least one annual growth increment. For cutting, some specialists rely on disposable blades, such as scalpels or heavy-duty razor blades, but a well-honed pocketknife will suffice.

The following tips will help: Once the surface is cut, touch it to your tongue or otherwise dampen it. This brings up the contrast and makes details easier to spot. Next, position the sample so it receives maximum light. Now, bring the hand lens up as close to the eye as possible so the field of view will be as wide as the lens can provide. Finally, move either the sample or your head until the scene is brought into focus.

From Fine Woodworking #73

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Ridgid R4331 Planer

DeWalt 735X Planer

AnchorSeal Log and Lumber End-Grain Sealer

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in