Synopsis: To build with mahogany is to share a woodworking experience with the skilled 18th- and 19th-century cabinetmakers who made some of the world’s most cherished furniture, writes Jon Arno. True mahoganies are in short supply, and Arno explains the challenges faced by the tree and those interested in using it. He shares information on the species, its historical perspective, its characteristics, and how to work with it. Side information covers mahogany look-alikes.

To build with mahogany is to share a woodworking experience with the skilled 18th- and 19th-century cabinetmakers who created some of the world’s most cherished furniture. Unfortunately, fewer woodworkers are able to savor that experience today, because the true mahoganies, what the old cabinetmakers called Cuban and Honduras mahoganies, are in short supply. The trees, often growing more than 100 ft. high and as much as 40 ft. around, are found in ever smaller and more remote groves. Most of the original stands have disappeared; those that remain have been heavily logged. Usually only a few mahogany trees, two or three per acre, constitute a “stand,” which makes logging inefficient and expensive. Harvesting is haphazard and often badly managed, with little thought given to ensuring adequate supplies for the future. Attempts to cultivate mahogany haven’t been very successful: The tree is slow growing, requiring 60 years to reach economically viable size, and many immature trees are destroyed by larvae of the widespread pyralid moth and ambrosia beetle. Also, the best of the highly figured lumber is often marked for use as veneer in production furniture shops or for interior decorative work, further depleting the supply. So mahogany, if you can find it, is expensive. For the real thing, cost can range between $5 and $10 per bd. ft. for clear, but plain-figured stock.

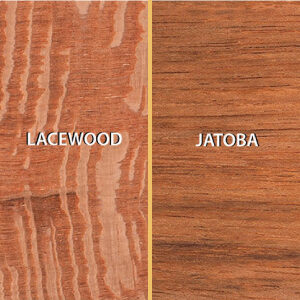

The true mahoganies come from several species in the genus Swietenia, but two species predominate: Swietenia mahagoni, the West Indies or island species, often called Cuban mahogany; and Swietenia macrophylla, the mainland species, found from east central Mexico to Bolivia, commonly called Honduras mahogany. With less true mahogany available, you’re likely to find lumberyards stocked with substitutes, such as African mahogany (khaya) or even totally unrelated timbers, such as lauan, the so-called “Philippine mahogany” or Australian “Red” mahogany, which is actually a Eucalyptus. Some of the substitutes, such as khaya, sapele and andiroba, are members of the mahogany family, which includes about 50 genera and nearly 1,000 species, and are fine cabinetwoods in their own right.

The differences between the substitutes and the real stuff aren’t always obvious, even to a practiced eye. It isn’t until you begin working with the woods that the real differences become apparant. True mahogany is easily worked and shaped. Its exquisitely Figured grain, hidden beneath the surface of roughsawn lumber, seems to come alive with a soft luster when planed.

From Fine Woodworking #76

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

AnchorSeal Log and Lumber End-Grain Sealer

Ridgid R4331 Planer

DeWalt 735X Planer

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in