Building a Tinware Cupboard

Flush panels modify a Shaker design

Synopsis: Christian Becksvoort’s Shaker tinware cupboard breaks all the rules of proportion. Because of its size, it’s useful all over the house, but it doesn’t adhere to the 1.6 to 1 design rule. This one has five movable shelves, and the top and sides are rabbeted to receive the back and are dovetailed together. He explains how he built the carcase, face frame, and frames and panels, with a detailed project plan showing all its parts. A side article explains how he hangs flush cabinet doors, and he adds to that with information on door bumpers, knobs, and spinners.

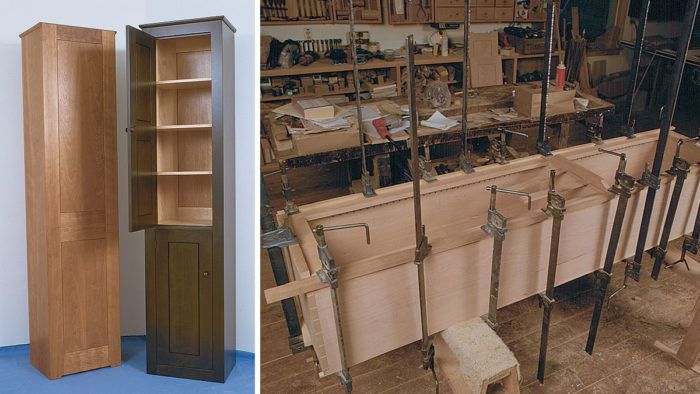

This Shaker tinware cupboard is a fascinating piece because it breaks all rules of proportion. The golden rectangle, a proportional principle used since ancient Greek civilizations, maintains that a height-to-width ratio of 1.6-to-l is most harmonious, and other proportions create conflict. Yet this cupboard’s size is what makes it one of the most versatile pieces I build. It is equally suitable in a hallway, bedroom, bath, kitchen or living room—anywhere space is at a premium-to store crystal, linens, clothes, camera equipment, papers, books, canned goods or even stereo components. My adaptation of the tinware cupboard is based on a Shaker original I saw at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., in 1973. Built in New Lebanon, N.Y., the dark red painted pine piece was probably used in a kitchen or pantry.

The first few cupboards I built were faithful reproductions, scaled from a photo. Since then I have made a few minor changes, such as lighter stock and movable shelves. I usually make the carcase from in.-thick edge glued cherry and use in.-thick stock for the face frame and doors. The top and sides are rabbeted to receive the back and are dovetailed together, while the fixed middle shelf and the bottom are dadoed into the sides. The bottom is also screwed to the sides through glue blocks. Visually and structurally, the most important changes were to replace both the slab back and raised-panel doors with frames and flat-flush panels, as shown here, which give the piece a distinctive look while accommodating the natural expansion and contraction of the solid-wood doors and back panels. The face frame and flat-flush back panel are mortised and tenoned, and then glued to the carcase, resulting in an extremely rigid piece. Because five of the shelves are adjustable, rather than fixed as in the original, the cabinet is adaptable to a variety of storage requirements. And, instead of exterior spinners and a lock, I use interior spinners operated by the doorknobs.

While I usually prefer an oil finish on natural cherry pieces, I was intrigued by John McAlevey’s article on ebonizing wood, a process that chemically dyes the stock, yet lets the grain show through. The Shakers often ebonized their chair frames, and so I thought why not an entire case? I experimented with one of my cupboards, making the carcase out of birch and leaving the interior natural to contrast with the dark ebonized exterior. When the doors are opened, the light, bright interior is a bit of a surprise, as you can see here.

From Fine Woodworking #83

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Sketchup Class

Stanley Powerlock 16-ft. tape measure

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in