James Krenov is as much a philosopher as he is a furnituremaker. People are drawn to his nine-month intensive course at the College of the Redwoods in Fort Bragg, Cal., the way that students of Zen are drawn to a renowned master: They come for a chance to have personal contact with the teacher. Krenov doesn’t promise to teach anyone how to make a living as a craftsman, as some woodworking programs have recently begun to do. Instead, he teaches how to make an object that is right in and of itself-one that looks right, feels right and works right. But it is not so much the object that is the lesson, but the making of the object. A reverence for the craft of woodworking will most surely be his greatest legacy. Judging from the furniture of about a dozen of his former students that was featured in a show celebrating Krenov’s 10th anniversary at the College of the Redwoods, the message is getting across. It will be through these students that Krenov will realize his ambition, as expressed in his third book, The Impractical Cabinetmaker, of bringing wider attention to a “quieter, richer expression” in the craft of woodworking.

The anniversary show, held at the Pritam and Eames Gallery in East Hampton, N.Y., last summer and aptly named James Krenov and Friends, was a reunion of sorts. Although Krenov has kept in touch with many of his former pupils, he was seeing some of their current work for the first time. Gallery owners BeBe and Warren Johnson also surprised Krenov by bringing in some of his older pieces to stand side by side with his current work.

Among Krenov’s recent work were several cabinets on stands, such as those on the left and right in the phot above in the left photo below. He has treated this particular furniture form dozens of times, and he confesses to feeling no embarrassment about returning to a design and working through it again. The maple wall-hung cabinet in the center of the photo above is another example of a recent variation on a familiar theme. But when the cabinet door is opened, a pleasant surprise is revealed: an uncharacteristic green painted interior.

|

|

| Photo left: Krenov built the teak and oak cabinet in 1989. He had intended to have a bridge of some kind spanning across the top of the cabinet, but when he couldn’t make it work visually, he decided it wasn’t meant to be and left it off.

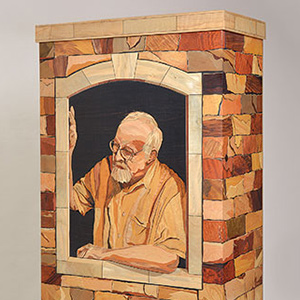

Photo right: The dogwood blossoms that decorate Jivko Radenkov’s cabinet seem to be blowing gently in the wind; a falling petal drifts slowly across the face of the elm-veneered door. As a student at the College of the Redwoods in 1983, Radenkov was hesitant to approach Krenov with the idea of using marquetry on one of his pieces, but he met no resistance and has gone on to refine this facet of his work. |

As rewarding as it was for me to see Krenov’s furniture firsthand after admiring it in books and magazines for many years, the other work in the show made the largest impression on me. While all the furniture bore certain Krenovian traits, such as careful selection of wood for grain and color or the telltale traces of having been finished using a scraper or handplane instead of sandpaper, most of the pieces were clearly the personal expressions of individual craftspeople. One of the best examples of this individuality was the elm-veneered cabinet, shown in the right photo above, by Cleveland, Ohio, furnituremaker Jivko Radenkov. One would never expect a Krenov-inspired piece to be decorated with marquetry, but Hadenkov has made it work by executing the marquetry with perfect precision and showing admirable restraint in the overall composition. William Walker, of Seattle, Wash., has also taken Krenov’s influence and applied it to a decidedly non-Krenovian purpose. Krenov has always shied away from building chairs, but Walker’s chairs were flawlessly executed and passed my sit-down test with flying colors. One of my favorite pieces at the show was the wall-hung jewelry cabinet shown in the three photos below by David Finck, of Reader, W.V. Finck’s asymmetrical treatment of the frame-and-panel door made me wonder why I ‘d never thought of that, and the inchworm door pull, which was made from pearwood and left unglued so that it swivels between its two mounting brackets, is as inviting and tactile as it is functional.

|

|

| The asymmetrical door on West Virginia furnituremaker David Finck’s jewelry cabinet is an eye-catcher. The door opens to reveal a stack of narrow drawers with bird’s-eye maple grain running continuously across their fronts. The pearwood door pull, above right, is as beautiful and tactile as it is functional. |

The afternoon that I visited the gallery, Krenov gave an informal slide presentation. One of the slides was of a clock that he had made many years ago that only had a second hand and an hour hand, but no minute hand. This was the perfect clock for a person reacting to a world in too much of a hurry, too obsessed with time. Krenov pointed out another interesting feature of this clock: The second hand tended to race downhill from the 12 to the 6 and then struggle slowly up the other side. However, he assured us that the clock was still right on time six months later. I always suspected that time was on Krenov’s side, and I’ll bet that the work of Krenov and his friends will still be right on 6 months or 60 years from now.

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Stanley Powerlock 16-ft. tape measure

Compass

Dividers

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in