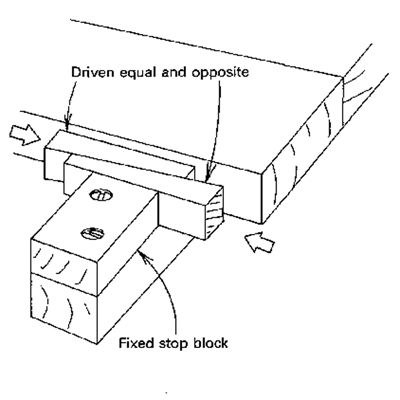

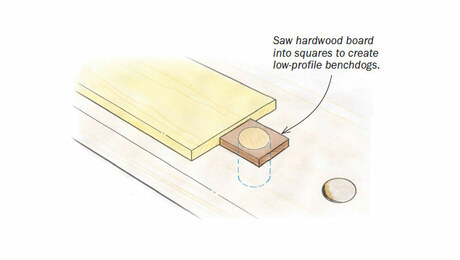

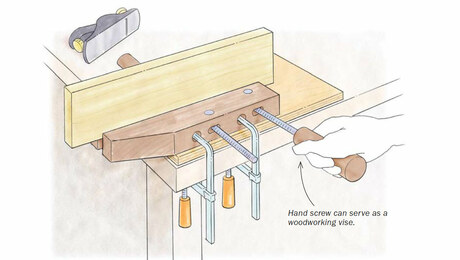

Synopsis: Percy W. Blandford learned how to apply wedge-clamping techniques to all his woodworking, a cheaper and sometimes simpler solution than using metal clamps. Here, he explains the principle behind wedge clamping and the most useful wedge-clamping methods he has employed. He says optimum wedge angle is hard to calculate, but in general, a wedge that rises about 1 in. in 6 in. makes a good choice. He addresses single vs. folding wedges, wedges as bar clamps, and other clamping situations. Illustrations show six ways to use wedges in clamping applications, and side information explains how integral wedges enhance joinery and ease assembly.

Like many woodworkers, I have found myself needing more clamps than I owned. Because of that, I began to use wedges as clamps, much like medieval artisans and builders who didn’t have any alternatives. Thanks to my early boat building experience, I learned how useful clamping with wedges can be and have since been able to apply wedge-clamping techniques to all my woodworking. And of course, cutting wedges from scrapwood is cheaper, and in some cases simpler, than using expensive metal clamps. In this article, I will discuss the most useful wedge clamping methods I have employed, but first, I’ll explain some basic wedge principles.

Wedge actions and properties

Whether you realize it or not, every time you drive in a screw or thread a nut onto a bolt, you are using wedge action. The threads of a screw or bolt can be considered a wedge of considerable length wrapped around a cylinder. If the thread is unwound, you get a long wedge with a very shallow slope (angle). Because of this, screws and bolts rely on many revolutions to advance themselves. But due to its shorter length, a plain wedge requires a steep angle to advance an object appreciably.

Optimum wedge angle is hard to calculate. A steep-angle wedge produces more movement, but requires more driving force. Plus, steep-angled wedges are more likely to slip than shallow-angled ones. Most of us rely on experience to choose a wedge’s angle, but for most clamping operations, a wedge that rises about 1 in. in 6 in. makes a good choice. Cabinetmakers might compare this with the average dovetail pitch of 1 in 7.

A wedge’s surface is also an important consideration. On the one hand, a wedge with a saw-cut surface has friction to resist slipping, which is good for clamping applications, but it is not as easy to drive as a wedge with a planed surface. On the other hand, a wedge that is meant to be removed periodically, such as those that are used in knockdown joinery (see the sidebar on p. 65), should have a smooth surface. And for a very slippery surface, naturally oily woods, like teak or lignum vitae, can be used to make self-lubricating wedges.

From Fine Woodworking #93

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

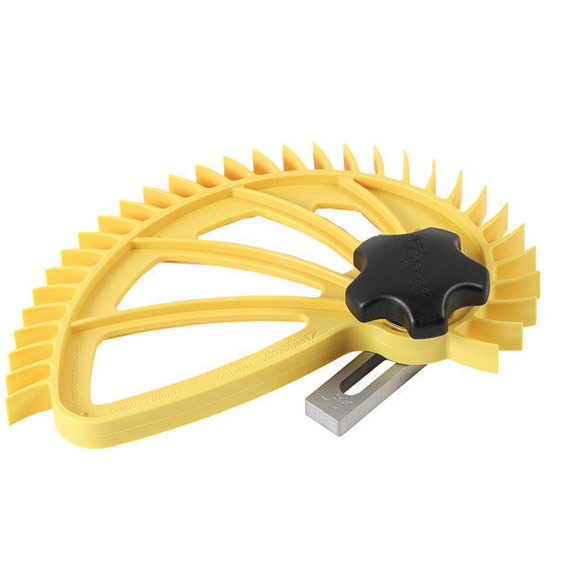

Hedgehog featherboards

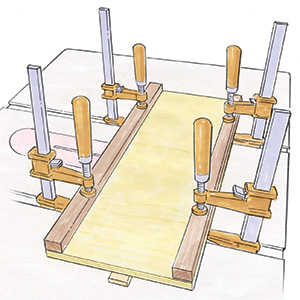

Bessey K-Body Parallel-Jaw Clamp

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in