Quick and Clean Bookcases

Lumberyard pine with biscuits make a sturdy bookcase

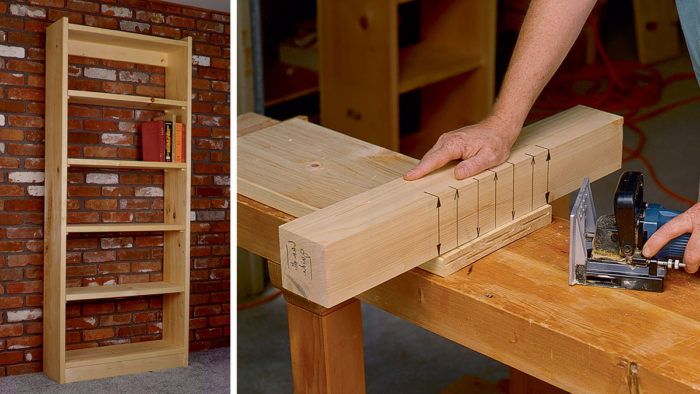

Synopsis: Much of what John Kelsey builds falls in the useful and sturdy category, though he also does make fine hardwood furniture. Here, he shares a design and technique for building bookcases that is economical of materials and time. He uses 5/4 #2 white pine for strength and availability, but advises you choose what’s plentiful in your area. He explains how to make the frameless, backless case with two cross-braces that prevent racking. He talks about sizing and crosscutting the parts, handplaning the boards, joining the parts with biscuits, and making support pegs. Side information offers help in selecting usable #2 pine.

Sure, I like to show off my finest pieces of hardwood furniture, but they’re only some of what I build. Much of the output from my home workshop is what I’d call useful and sturdy rather than highly refined or fancy.

Bookcases, for example. In a lifetime of woodworking, publishing and book collecting, I’ve had to house yards and yards of books. I’ve evolved a design and a technique that’s right for the task and also right for my tools and for my own style of working.

The last points, appropriateness to my shop and how I like to work, are perhaps the most important. I don’t have a big investment in machinery, and I don’t have to earn a living woodworking. I do it because making things with my hands helps me stay sane.

Basic bookcases

When your books are breeding uncontrollably, what defines an appropriate design solution? A bookcase performs an essentially utilitarian task, so these units should be economical of materials and time. The shelves have to be as deep as the books and adjustable in height, or else they waste space and the books will gather dust; shelves can’t sag under the considerable weight of art books, LP records or magazines; the case should be reasonably sized and not too big—you don’t often move them, but when you do, they have to thread through doorways, up stairs and down hallways. Finally, wood surfaces should be worked to a quality that can be painted, varnished or left unfinished.

The way I approach utility problems like this is not through function but through material. The question is, what’s the best local deal you can find? When I lived in Ohio, 4/4 poplar offered the most wood for the buck. Farther north in New England, it might be maple or birch. But around here in Connecticut, it’s 5/4 #2 western white pine from the local lumberyard. This wood has all the right characteristics: it’s sturdy, it’s cheap, it’s already planed and it’s available. Books are heavy, so the wood’s thickness is important. The approach I’m describing here does not work with 4/4 #2 pine, which is just not stiff enough.

The basic bookshelf design I’ve evolved, as shown in the drawing 011 p. 65 and the photo at right, is a face frame-less, back-less case with two cross braces to resist racking. The case sides extend beyond the top and bottom shelves, which join to the sides with plate-joinery biscuits. Adjustable shelves held by hand-whittled pegs make the case more versatile and also lend it a touch of crafty charm.

From Fine Woodworking #98

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Sketchup Class

Olfa Knife

Marking knife: Hock Double-Bevel Violin Knife, 3/4 in.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in