Sanding in Stages

Breaking up the job eliminates drudgery, yields better results

Synopsis: No matter how much time and care go into the making of a piece, its overall beauty is partly determined by how well it has been sanded. No finish can cover up a mediocre sanding job. If you divide the labor into stages, he advises, it’s easier to endure. In this article, Gary Straub explains how sandpaper is made now and how to choose the best kind for your projeck, and how to sand and get better results without monotony, using machines or hand tools. Straub’s method is to plane all lumber before sanding. He also addresses smoothing the finish with mineral spirits, a rottenstone, and felt.

Everything from sharp stones to sharkskin has been used to smooth wood. Today there’s a seemingly endless array of sanding tools, aids and abrasives available, all designed to make our work faster, easier and better. If we look back at the methods used to smooth wood, we should appreciate the ease with which we can produce results far superior to those of our predecessors. Even so, most woodworkers still dread sanding.

That’s too bad because sanding is one of the most important aspects of producing a fine piece. No matter how much time and care go into the making of a piece, its overall beauty is in large measure determined by how well it’s been sanded. Although some finish representatives will tell you differently, no finish can cover up a mediocre sanding job.

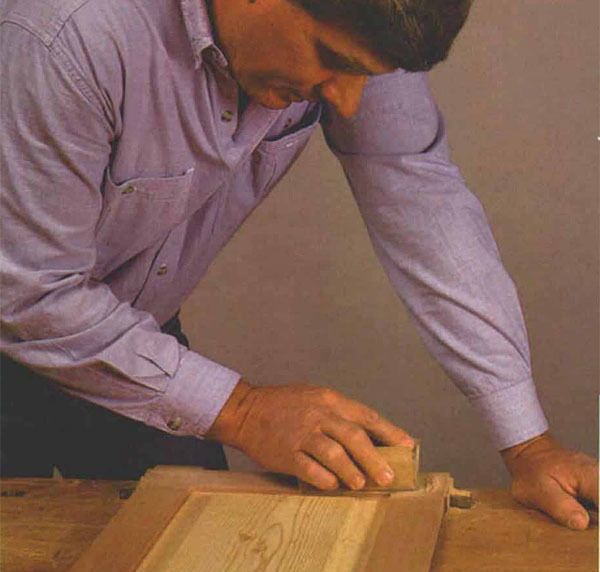

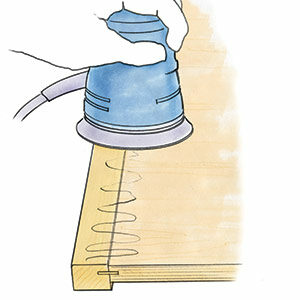

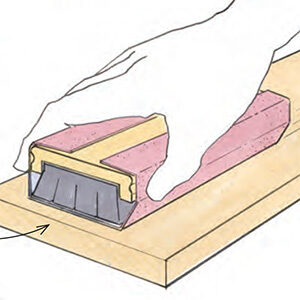

Sanding doesn’t have to be sheer drudgery, however, if you break the job down into its various stages and integrate the smoothing process with the construction of a piece of furniture. Before I’ve even ripped a board to width or crosscut it to length, I’ve beltsanded it to 100-grit. I remove all flaws with this preliminary sanding so that the only reason for further sanding is to remove the scratches created by the previous coarser grit. By the time I glue-up, everything’s been sanded to 150-grit, which makes post-assembly sanding a breeze.

The result of this division of labor is a better sanding job, less tedium and a finer finished piece. The sanding system I’ve developed over the past twenty years of furniture making takes advantage of a wide range of abrasive materials. But before I explain my techniques, let’s look at what’s available today.

The materials

Sandpaper was invented when someone figured out how to glue screened panicles of glass or sand onto a paper backing. Today, of course, true sandpaper and glasspaper are practically unavailable. They have been replaced by papers that use much harder and sharper minerals, both natural and synthetic. New abrasive materials, more sophisticated screening methods and superior papers and glues have transformed the ways we smooth wood. Not long ago, abrasives came in grits from 12 to 600; now they go into the thousands (see the photo on the facing page). As if that weren’t enough, we also have steel wool, abrasive cloths, pads, powders, liquids and pastes. Knowing what to use has become a challenge.

From Fine Woodworking #99

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Festool Rotex FEQ-Plus Random Orbital Sander

Preppin' Weapon

Double Sided Tape

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in