Making an End Table

The beauty of this Arts-and-Crafts design is in the detailsAbout 10 years ago, I began to tire of my job as a corporate pilot. The work was challenging and enjoyable, but the time away from home put a strain on my family. The job was becoming more technical, too. Temperamentally, I’ve always been more of a craftsman than a technician.

After considerable soul-searching, I decided to become a furnituremaker. I wanted a solid foundation of basic skills, so I went to England where I trained with Chris Faulkner. He emphasized developing hand-tool skills and building simple, comfortable furniture that asked to be used–a basic tenet of the British Arts-and-Crafts movement. My preferences to this day are for this kind of furniture and for the use of hand tools whenever their use will make a difference.

About two years ago, I designed and built this end table. Although it’s an original design, many details come from other pieces of furniture in the British Arts-and-Crafts tradition. The joinery is mortise-and-tenon and dovetail throughout.

The construction of the table can be divided into five main steps: stock preparation and panel glue-up; making the front and rear leg assemblies; connecting these two assemblies (including making the shelf and its frame); making and fitting the drawer; and making and attaching the top.

Stock selection, preparation and layout

I milled all the stock for this table to within 1/16 in. of final thickness and width. I also glued up the tabletop, the shelf and the drawer bottom right away to give them time to move a bit before planing them to final thickness. This helps ensure they’ll stay flat in the finished piece. With these three panels in clamps, I dimensioned the rest of the parts to a hair over final thickness. I finish-planed them by hand just before marking out any joinery.

Making the front and rear assemblies

Keeping track of the legs is easier when they’re numbered on top, clockwise from the front left. This system helps prevent layout errors. Layout began with the legs. I numbered them clockwise around the perimeter, beginning with the left front as I faced the piece, writing the numbers on the tops of the legs. This system tells me where each leg goes, which end of a leg is up and which face is which.

Keeping track of the legs is easier when they’re numbered on top, clockwise from the front left. This system helps prevent layout errors. Layout began with the legs. I numbered them clockwise around the perimeter, beginning with the left front as I faced the piece, writing the numbers on the tops of the legs. This system tells me where each leg goes, which end of a leg is up and which face is which.

Dovetailing the top rail into the front legs

The dovetails that connect the top rail to the front legs taper slightly top to bottom. I used the narrower bottom of the dovetail to lay out the sockets in the legs. The slight taper ensures a snug fit. Don’t make the dovetails too large, or you’ll weaken the legs.

After I marked, cut and chopped out the sockets, I tested the fit of these dovetails. By using clamping pads and hand screws across the joint, I eliminated the possibility of splitting the leg. The dovetail should fit snugly but not tightly. Pare the socket, if necessary, until you have a good fit.

Scribing the socket from the bottom of the slightly tapered dovetail ensures a good fit in the leg.

Scribing the socket from the bottom of the slightly tapered dovetail ensures a good fit in the leg.  A hand screw prevents a leg from splitting if the top-rail dovetail is too big. The fit should be snug but not tight.

A hand screw prevents a leg from splitting if the top-rail dovetail is too big. The fit should be snug but not tight.

Tapering and mortising the legs

I tapered the two inside faces of each leg, beginning 4-1/2 in. down from the top. I removed most of the waste on the jointer and finished the job with a handplane. The tapers must be flat. To avoid planing over a penciled reference line at the top of the taper, I drew hash marks across it. With each stroke of the plane, the lines got shorter. That let me know how close I was getting.

I cut the mortises for this table on a hollow-chisel mortiser. It’s quick, and it keeps all the mortises consistent. I made sure all mortises that could be cut with one setting were done at the same time, even if I didn’t need the components right away.

Tenoning the aprons and drawer rail

I tenoned the sides, back and lower drawer rail on the tablesaw, using a double-blade tenoning setup. It takes a little time to get the cut right, but once a test piece fits, tenoning takes just a few minutes. After I cut the tenon cheeks on the tablesaw, I bandsawed just shy of the tenon shoulders and then pared to the line.

One wide apron tenon would have meant a very long mortise, weakening the leg. Instead, I divided the wide tenon into two small tenons separated by a stub tenon. That left plenty of glue-surface area without a big hole in the leg.

Chamfering and gluing up

Check diagonals to make sure assemblies are glued up square. Clamps and a spacer at the bottom of the legs prevent the clamping pressure at the top from causing the legs to toe in or out. Stopped chamfers are routed on the legs and aprons of this table, each terminating in a carved lamb’s tongue. I stopped routing just shy of the area to be carved and then carved the tongue and the little shoulder in three steps. (see the Carving a lamb’s tongue section below)

Check diagonals to make sure assemblies are glued up square. Clamps and a spacer at the bottom of the legs prevent the clamping pressure at the top from causing the legs to toe in or out. Stopped chamfers are routed on the legs and aprons of this table, each terminating in a carved lamb’s tongue. I stopped routing just shy of the area to be carved and then carved the tongue and the little shoulder in three steps. (see the Carving a lamb’s tongue section below)

Gluing up the table base is a two-step process. First I connected the front legs with the top and bottom drawer rails and the back legs with the back apron. To prevent the legs from toeing in or out because of clamping pressure, I inserted spacers between the legs at their feet and clamped both the top and bottom. Then I check for square, measuring diagonally from corner to corner. It ensures that the assembly is square and that the legs are properly spaced.  Step 1: Pare to marked baseline. Strive for a fair, even curve, and cut down toward the chamfer.

Step 1: Pare to marked baseline. Strive for a fair, even curve, and cut down toward the chamfer.  Step 2: Tap a stop for the shoulder at the baseline. Avoid cutting too deeply; just a light tap is needed.

Step 2: Tap a stop for the shoulder at the baseline. Avoid cutting too deeply; just a light tap is needed.  Step 3: Pare into stop to create a shoulder. You have to cut toward the shoulder, so take light cuts and watch which way the grain is running. If you must pare against the grain, make sure your chisel is freshly honed.

Step 3: Pare into stop to create a shoulder. You have to cut toward the shoulder, so take light cuts and watch which way the grain is running. If you must pare against the grain, make sure your chisel is freshly honed.

Connecting the front and rear assemblies

To hold the legs in position while I measured for the drawer runners and kickers and, later, to get the spacing on shelf-support rails correct, I made a simple frame of hardboard and wooden corner blocks. The frame ensures the assembly is square and the legs are properly spaced. After I marked the shoulder-to-shoulder lengths for the runners and kickers, I cut and fit the stub tenons that join these pieces to the front and rear assemblies. The back ends of the runners and kickers must be notched to fit around the inside corners of the legs.

A simple frame keeps the legs spaced accurately and the base of the table square. A 1/4-in.-thick piece of hardboard and some scrap blocks make up this handy frame. With the legs properly spaced, the author can mark the shoulders of the shelf-frame rail against the tapered legs as well as take precise measurements for runner and kicker lengths.

Runners, kickers and dust panel

I cut the 1/4-in. grooves for the dust panel in the drawer runners next. I also cut grooves for the splines with which I connected the drawer runners and kickers to the sides of the table. There are 10 grooves in all–one each on the inside and outside edges of the drawer runners, one on the outside edge of each of the kickers and two in each side for the splines.

Then I dry-clamped the table and made sure the tops of the kickers were flush with the top edges of the sides, the tops of the runners flush with the top of the drawer rail and the bottoms of the runners flush with the bottom edges of the sides. Then I cut the dust panel to size, test-fit it and set it aside until glue-up.

Building the shelf frame and shelf

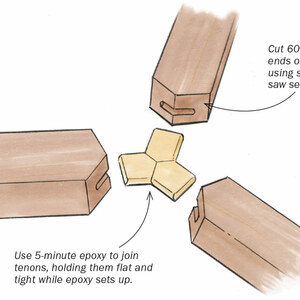

The shelf on this table is a floating panel captured by a frame made of four rails. The two rails that run front to back are tenoned into the legs; the other two are joined to the first pair with through-wedged tenons.

I put the dry-assembled table into the hardboard frame and clamped the legs to the blocks. Then I clamped the pair of rails that will be tenoned into the legs against the inside surfaces of the legs and marked the shoulder of each tenon. I also marked the rails for orientation so that the shoulders can be mated correctly with the legs.

Tenons were cut and fit next. With the rails dry-clamped into the legs, I measured for the two remaining rails to be joined to the first pair. I laid out and cut the through-mortises in the first set of rails, chopping halfway in from each side to prevent tearout. I cut the tenons on the second set of rails, assembled the frame and marked the through-tenons with a pencil line for wedge orientation. So they don’t split the rails, the wedges must be perpendicular to the grain of the mortised rail.

I flared the sides of the through-mortises (not the tops and bottoms) so the outside of the mortise is about 1/16 in. wider than the inside. This taper, which goes about three-quarters of the way into the mortise, lets the wedges splay the tenon, locking the rail into the mortise like a dovetail.

Next I marked the location of the wedge kerfs in each tenon, scribing a line from both sides of the tenon with a marking gauge for uniformity. I cut the kerfs at a slight angle. Wedges must fill both the kerf and the gap in the widened mortise, so they need to be just over 1/16 in. thick at their widest.

An interlocking tongue and groove connects the shelf to the rails that support it. Using a 1/4-in. slot cutter in my table-mounted router, I cut the groove in the rails, working out the fit on test pieces first. The slots are 1/4 in. deep. I stopped the grooves in the rails 1/8 in. or so short of the mortises on the side rails and short of the tenon shoulders on the front and back rails. I notched the shelf to fit at the corners.

I measured the space between the rails of the shelf frame and added 1/2 in. in each direction to get the shelf dimensions. I cut the tongue on all four edges on the router table.

Gluing up the shelf-frame assembly

Before gluing up the shelf frame, I routed hollows in clamp pads to fit over the through-tenons on two of the shelf rails. Then I began gluing up the shelf assembly. I applied glue sparingly in the mortises and on the tenons so I wouldn’t accidentally glue the shelf in place. I pulled the joints tight with clamps and then removed the clamps temporarily so I could insert the wedges.

After tapping the lightly glue-coated wedges into the kerfs in the tenons, I reclamped the frame. I checked diagonals and adjusted the clamps until the assembly was square. Once the glue was dry, I sawed off the protruding tenons and wedges and planed them flush.

Overall glue-up

With the shelf frame glued up, the entire table was ready to be assembled. I began the large front-to-back glue-up by dry-clamping the front and back leg assemblies, sides, runners, kickers (with splines), dust panel and shelf assembly. I made adjustments and then glued up.

I made and fit the drawer guides next. I glued the guides to both the sides and the runners and screwed them to the sides with deeply countersunk brass screws.

I did a thorough cleanup of the table in preparation for drawer fitting. I removed remaining glue, ironed out dents and sanded the entire piece with 120-grit sandpaper on a block. I gently pared sharp corners, taking care not to lose overall crispness.

The drawer

I particularly enjoy making and fitting drawers. A well-made drawer that whispers in and out gives me great satisfaction. I use the traditional British system of drawermaking, which produces what my teachers called a piston fit. The process is painstaking (see FWW #73, pp. 48-51 for a description of this method), but the results are well-worth the effort. That, however, is a story for another day.

Making and attaching the top

After I thicknessed and cut the top to size, I placed it face down on my bench. I set the glued-up base upside down on the top and oriented it so it would have a 1-in. overhang all around. I marked the positions of the outside corners and connected them with a pencil line around the perimeter. This line is one edge of the bevel on the underside of the top. Then I used a marking gauge to strike a line 7/16 in. from the top surface on all four edges. Connecting the two lines at the edges created the bevel angle. I roughed out the bevel on the tablesaw and cleaned it up with a plane. The bevels should appear to grow out of the tops of the legs.

Making and attaching the coved lip

Rabbeted clamping block helps provide pressure in two planes. The author clamps down the cove strip with six C-clamps and into the rabbet with six bar clamps. A spring clamp on each end closes any visible gaps at the ends. The cove at the back of the top is a strip set into a rabbet at the back. I cut the cove from the same board I used for the top so that grain and color would match closely. I ripped the cove strip on the tablesaw and handplaned it to fit the rabbet. I shaped the strip on the router table, leaving the point at which it intersects the top slightly proud. To provide even clamping pressure, I used a rabbeted caul, clamping both down and in.

Rabbeted clamping block helps provide pressure in two planes. The author clamps down the cove strip with six C-clamps and into the rabbet with six bar clamps. A spring clamp on each end closes any visible gaps at the ends. The cove at the back of the top is a strip set into a rabbet at the back. I cut the cove from the same board I used for the top so that grain and color would match closely. I ripped the cove strip on the tablesaw and handplaned it to fit the rabbet. I shaped the strip on the router table, leaving the point at which it intersects the top slightly proud. To provide even clamping pressure, I used a rabbeted caul, clamping both down and in.

When the glue was dry, I planed the back and the ends of the cove flush with the top. To form a smooth transition between top and cove in front, I used a curved scraper, followed by sandpaper on a block shaped to fit the cove. I frequently checked the transition with my hand and sanded a wider swath toward the end. It’s easy to go too far and have a nasty dip in front of the cove.

I drew the ends of the cove with a French curve and then shaped the ends with a coping saw, chisel and sandpaper. The curve should blend into the tabletop seamlessly.

Finishing up with oil

After finish-sanding, I applied several coats of raw linseed oil diluted with mineral spirits in a 50/50 mix, a few more coats of straight linseed oil and, finally, two to three coats of tung oil to harden the surface. I let the oil dry thoroughly between coats. After the last coat of oil was dry, I rubbed the surface down with a Scotch-Brite pad and gave the table a few coats of paste wax. The drawer was the exception: Aside from the face of the drawer front, all other surfaces were finished with wax alone.

Attaching the top

I screwed the top to the top-drawer rail from beneath to fix its position at the front. That way, the mating of the bevel with the front rail will be correct and any seasonal movement of the top will be at the back. I attached the top to the base with buttons on the sides and in the rear.

Photos: Vincent Laurence; drawings: Bob La Pointe

From Fine Woodworking #120, pp. 48-53

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in