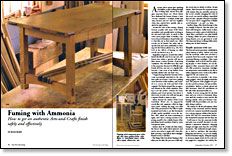

Fuming with Ammonia

How to get an authentic Arts-and-Crafts finish safely and effectively

Synopsis: When many people think of Stickley, Limbert, or Roycroft furniture, fumed white oak is what they see in their mind’s eye. Kevin Rodel explains the history and methods behind ammonia fuming, starting with how to use it safely. Use boards cut from the same tree; otherwise, tannin levels will vary, and so will your result. Then he addresses how to build a fuming chamber and prepare the lumber for a stay inside the chamber. A photo chart compares fumed, unfumed, and tannic acid fumed maple, birch, cherry, and butternut, unfinished and finished with oil. Side information offers a look at how common furniture woods look when fumed and finished in various ways.

Anyone who’s spent time mucking out stables, or just walking through a working barn, knows how pungent ammonia fumes are. Those fumes have darkened the beams of many a barn over the centuries. I wouldn’t doubt that many farmers put two and two together when they noticed how quickly oak acquired an aged patina.

Around the turn of the century, fuming became popular with many of the furnituremakers and manufacturers working in the Arts-and-Crafts style. So much so that when most people think of Stickley, Limbert or Roycroft furniture, fumed white oak is what they see in their mind’s eye. Other woods can be fumed, but white oak responds best and most predictably to fuming (see the bottom photos on p. 48). For a look at the effects of fuming on other woods, see the box on p. 49.

Regardless of species, boards that will be fumed should all come from one tree. Different trees within a species will vary in their tannin content because of growing conditions. This will affect how they react to the ammonia. Because it’s difficult to get boards all from one tree at a regular lumberyard, I buy most of my lumber from specialty dealers who saw their own.

I began fuming furniture because I’d become increasingly interested in the Artsand-Crafts movement. I had been making more furniture in that tradition, and I wanted it to convey the look and feel of the originals. The finish seemed like an important element in the whole equation. Fuming is not the perfect colorant for every situation and wood species, but where it does work, it works very well and can give a superior finish to stains or dyes.

Stains obscure the surface of the wood somewhat. Worse yet, on ring-porous woods like oak, pigments collect in large open pores, making the rings very dark and overly pronounced. The effect is quite unnatural and looks to me like thousands of dark specks sprinkled across the surface. Also, stains are time-consuming to apply, and I have a strong aversion to exposing myself to the volatile fumes of the petroleum-based products found in most commercial stains.

Aniline dyes do a better job than stains, but they’re also rather labor-intensive and can be very tricky to apply well. Dyes also fade over time, especially in direct sunlight. Fumed wood is colorfast.

From Fine Woodworking #126

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Double Sided Tape

Tite-Mark Marking Gauge

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in