Boring Big Holes

When to use Forstners, Multispurs, spades, hole saws and wing cutters

Synopsis: When Robert M. Vaughan faced a job that involved drilling 18,000 holes, he investigated drill-bit methods to see what would serve him best. (This article deems anything larger than 5/8-in. dia. as a big hole.) If you are faced with a similar job, ask yourself a few questions before spending money: how often will you need to drill the holes, what precision of cut is required, and how quickly will you need to get the job done. The article details each type of bit and recommends bits for different jobs: For precision holes, choose a Forstner or Multispur bit. For fast drilling, go with a spade bit. Hole saws are good for installing locksets, and wing cutters and circle cutters are adjustable. The article also explains the difference between cheap bits and pricey ones, and details how the 3D-Bit works.

From Fine Woodworking #129

Many years back, I had a commission to build lockset displays. The job called for 18,000 holes with smooth bores and crisp edges in blocks of 1-3/4-in.-thick oak. At a flat rate of 9 cents a hole, I couldn’t afford to let the wrong drill bits slow me down.

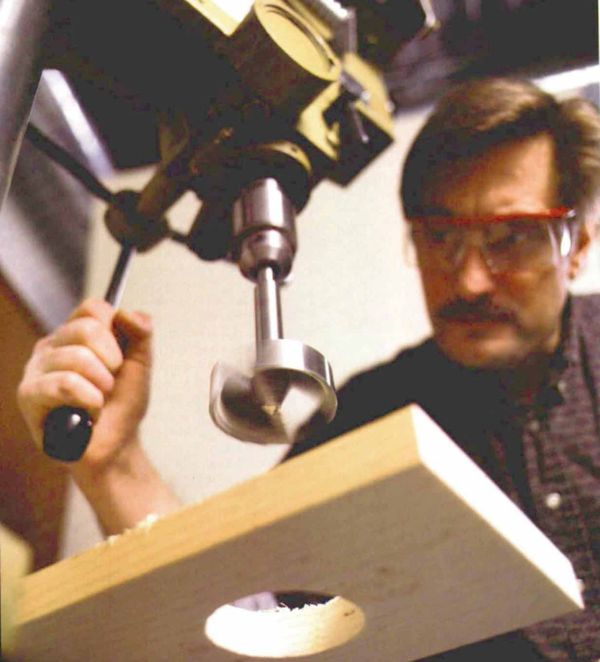

Before beginning, I experimented with a variety of methods. I settled on Multispur bits chucked in a drill press. They produced precise, tearout-free holes and allowed me to work fast enough that I finished the job in a little over a week. Depending on the project, other large-hole boring tools might be worth considering. The most common tools include Forstner bits, spur bits, spade bits, hole saws and wing cutters.

Furniture, craft projects, architectural work, and home repairs often call for boring large holes. Large in my book is anything more than 5/8 in. dia., bigger than most commonly available twist drill bits. Big holes demand special bits, and the variety on the market includes everything from inexpensive high-carbon-steel spade bits to costly Forstners.

Before spending a wad of cash on a set of bits, consider how often you need to drill large holes, the precision of cut required and how quickly you need to get the job done.

Like life forms, tools evolve over time, only much faster. Forstners were developed more than 100 years ago for use in hand braces. They were an improvement over the other bits of the time, such as brace bits, because Forstners could drill overlapping and flat-bottomed holes. Forstners cut on two fronts: A sharp outer rim continuously scores the wood, and a pair of horizontal cutting wedges removes most of the waste inside the hole and shaves the bottom flat.

If brace bits were life forms, they’d be the fish of boring tools. Forstners are the amphibians. The 20th century saw yet another major evolution: Forstners emerged from the swamp with teeth along their rims. Although it would seem that this would give the bit a bigger bite, something more significant happened. Like mammals, these sawtooth Forstners were more efficient at heat regulation. Getting rid of the solid rim meant less metal-to-wood contact, which creates heat-producing friction. With the advent of power tools, a cooler-running bit was needed. Smooth-rimmed Forstners, especially those 1 in. and greater in diameter, tend to scorch wood when used in an electric drill.

For the full article, download the PDF below.

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Starrett 12-in. combination square

Stanley Powerlock 16-ft. tape measure

Festool DF 500 Q-Set Domino Joiner

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in