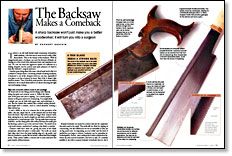

The Backsaw Makes a Comeback

A sharp backsaw won't just make you a better woodworker; it will turn you into a surgeon

Synopsis: With its swaged metal spine, a backsaw can carry the thinnest of blades, allowing it to slice wood with minimum waste and maximum control, writes Zachary Gaulkin. Best of all, it doesn’t take much to master. Success is not so much about skill as it is about choosing the right saw and keeping it sharp. Depending on your wallet and the level of perfection you hope to achieve, backsaws can be somewhat interchangeable as far as ripping and crosscutting goes. Gaulkin describes how Japanese saws work and why it’s smart to leave sharpening your backsaw to a professional. Then several woodworkers weigh in on their favorite backsaws and how they measure a saw’s worth.

From Fine Woodworking #129

There is an old truth buried under mountains of machine-made sawdust—the best way to sever wood is with a thin, sharp blade. This is the beauty of the backsaw. With its swaged metal spine, a backsaw can carry the thinnest of blades, allowing it to slice wood with minimum waste and maximum control. No one can deny the aggressive speed of a tablesaw or a sliding chopsaw, but for joinery (and quiet pleasure) it’s hard to beat the backsaw’s surgical precision.

Another great thing about this most critical hand tool is that it is a whole lot cheaper than a screaming armada of cutting machines. A backsaw is one of the cheapest tools you can buy, especially if you plan to do lots of joinery by hand. Best of all, it doesn’t take much to master. True, it involves some practice, but success with a backsaw is not so much about skill as it is about choosing the right saw and keeping it sharp.

All wood saws do two things and two things only: they rip along the grain and crosscut across it. Follow the direction of the grain and you’re ripping. Cut a board perpendicular to the grain and you’re crosscutting. You might think a simple saw can do both with equal ease, and sometimes it can. But the ripsaw that seemed like a scalpel cutting dovetail pins might leave a crosscut, such as a tenon shoulder, looking a little chewed up.

A saw’s ability to rip or to crosscut lies in the geometry of its teeth—the size, shape and set, or the amount they are bent away from the blade. Rip teeth usually are bigger than crosscut teeth, their cutting faces are nearly straight up and down and flat across, and they have a small amount of set. The big teeth shave away material fast, and the deep gullets (the valleys between the teeth) give the shavings a place to go so the saw won’t bind. The small set on a rip tooth creates a narrow kerf, making it less likely to wander.

Crosscut teeth have more set, giving the body of the blade (sometimes called the plate) a wider path. The teeth are raked back (they don’t have the steep leading edge of a rip tooth), and they are beveled to a point like an incisor, rather than filed straight across. These points enable a crosscut saw to score and sever the grain cleanly, without tearout.

For the full article, download the PDF below.

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Tite-Mark Marking Gauge

Veritas Precision Square

Stanley Powerlock 16-ft. tape measure

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in