Where Furniture Meets the Floor

These four traditional bases change the look and style of the same chest

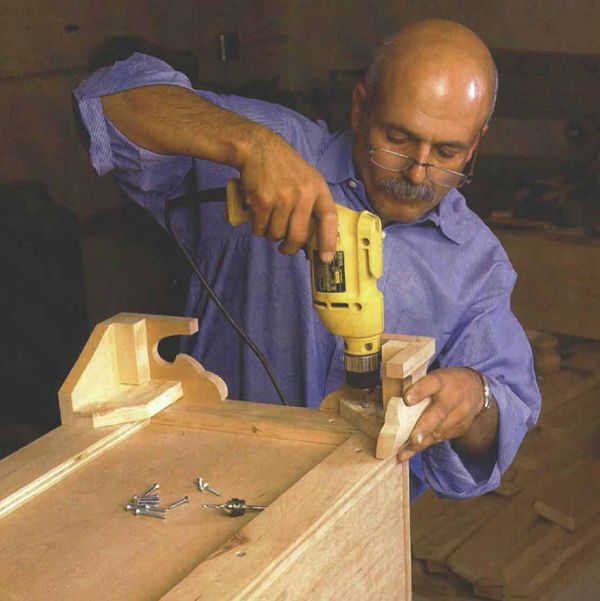

Synopsis: Careful base selection is critical to a successful piece. In this article, Mario Rodriguez builds a simple chest and alternatingly adorns it with bun feet, saber feet, sled feet, and with ogee bracket feet, and he shows how easy they are to make. He explains why you need a base at all, shares the history and evolution of each type, and gets right down to showing how to make them. Bun feet are produced on the lathe and have a tenon at the top. He includes a template to cut a saber foot, which is done on a bandsaw. Sled bases are two parallel feet joined by a beam; the foot’s shape and finish must be crisp. There are a few ways to make ogee molding, and Rodriguez shares how he does it with an angled fence on the tablesaw. Photos and side demonstration details guide you through the construction processes.

During the 1980s, when I operated a shop in Brooklyn, we received a steady stream of plain-Jane chests that had been picked up by interior decorators on their trips to the countryside or abroad. I was instructed to give these chests the “Cinderella treatment”—to revitalize them by changing the hardware, possibly adding stringing to the drawer fronts, or maybe making a new top.

By far the most dramatic change took place when I replaced a base. With a new base, a piece would assume a new personality. If I added just the right bracket feet, say, a mundane Victorian behemoth could be transformed into an elegant Chippendale-style treasure. The careful selection of the base proved, time and again, to be critical to the success of the completed piece. And I’ve found just the same thing to be true in designing my own pieces or adapting period designs.

To demonstrate the impact that different attached bases can have on a basic chest and to show how approachable most are to make, I’ve built a single, unadorned chest of drawers and fitted it with four different bases: with bun feet, with saber feet, with sled feet and with ogee bracket feet. All four of these bases are drawn from historical examples, but as you’ll see, they can easily be adapted to modern designs as well.

Why you need a base

A chest is essentially a box on a base. The box is where the action is—the drawers, the doors, the shelving. So the base, resting right on the floor, might seem likely to fall beneath our notice. But its impact is strong. First, it literally lifts the cabinet off the floor. The air it puts beneath the piece gives the cabinet definition and makes even an armoire appear lighter. Plunked right on the floor without a base, a large cabinet looks stunted and incomplete; it begins to seem immovable, like a part of the building. A Newport secretary minus its bracket feet would be about as impressive as the Statue of Liberty standing knee-deep in New York harbor.

The proper base should not only elevate the case but also enhance the other features of it. Instead of concentrating all of the detailing on the case and treating the base as an afterthought, I work out the details of the base along with the case.

My choice of a base is influenced by the size and weight of the piece. For instance, I wouldn’t place a massive, multidrawer chest on dainty saber feet. Structurally, the feet might not support the great weight of the piece and its contents.

From Fine Woodworking #135

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Bessey K-Body Parallel-Jaw Clamp

Bessey EKH Trigger Clamps

Festool DF 500 Q-Set Domino Joiner

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in