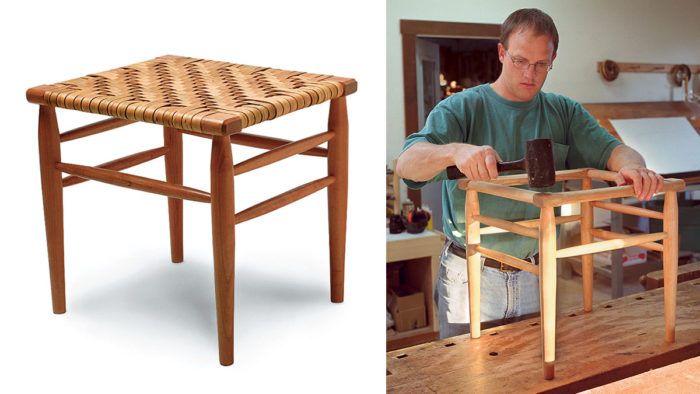

A Post-and-Rung Stool with Round Joints Built to Last

Learn a nontraditional approach to stool building that simplifies round-tenon joinery without sacrificing strength.

Synopsis: Here’s an exercise to perfect your round joinery skills. The author uses his experience of having built more than 1,500 chairs to guide you through every step: choosing the right materials, the differences between traditional and hybrid joints, making the seat frame, drying the rungs and legs properly and turning them, and cutting good tenons. He details how to drill the legs and assemble the undercarriage and attach the seat frame. There’s also information on how to weave a bark seat.

I suspect that for many readers the idea of building a simple stool seems rather mundane. But when taken as an exercise in perfecting your round joinery, there is more challenge here than meets the eye. Even after building 1,500 chairs, making a perfect round joint keeps me on my toes.

And there are lots of other reasons to get into stool making. Apart from providing compact, inexpensive seating, stools can serve as steady footrests and portable desks. Also, they can be adapted to serve as benches or bar stools or even as end tables or coffee tables. Finally, if you’ve never made a chair, a stool is a great first step. All of the joints in this stool are at 90°.

While there are lots of ways to construct a stool, I prefer the post-and-rung frame. It’s very lightweight, which is important because the stool will be moved around. Also, the round rungs can withstand a lot of racking and twisting without damaging the joint. And the parts, including the tenons, can be turned fairly quickly, and the mortises are simply drilled.

Round joints built to last

Round joints are often seen as a cheap, inferior way to join wood parts. After all, this is the joint in ladderback chairs that has kept many repair shops busy and many chair owners frustrated. But there are very old chairs with round joints that have held up for generations of use. My mother-inlaw has a fine example of a post-and-rung chair that’s more than 200 years old. The joints are in great shape, and there is no evidence of repairs. So, how can we make our chairs do that? There are at least two ways, and I have used them both.

The traditional method—The old locking joint is the most interesting. There are three requirements for success. First, the rung should be made of a very tough wood, such as oak or hickory, and the leg should be a slightly more elastic wood, such as maple. Second, the tenon is left slightly oversized, and a small notch is cut into it. Finally, the leg needs to have a high moisture content at the time of assembly— between 15% and 20%—with the rung dried to 4% or less. As the leg dries and shrinks, the mortise deforms to the shape of the notched tenon, locking the joint. Glue is not necessary and may even weaken the joint by filling the locking notch.

From Fine Woodworking #150

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Festool DF 500 Q-Set Domino Joiner

Suizan Japanese Pull Saw

AnchorSeal Log and Lumber End-Grain Sealer

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in