Building a Shaker Wall Clock

Choose your movement first, then build the clock around it

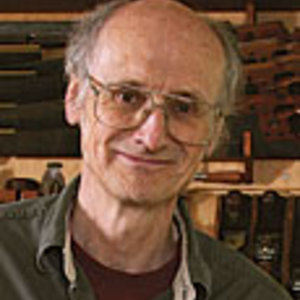

Synopsis: Contributing editor Christian Becksvoort demonstrates the construction of a Shaker-style clock in this article with detailed project plans. Using an original clock for inspiration, Becksvoort demonstrates universal techniques for clockmaking while building a classic piece from cherry. He offers several options for construction so you can choose how closely you will follow the original. Among the tips he shares to perfect your clock are making the case to fit the clock parts, not the other way around, and fitting the door. Side information discusses clock movements, custom dials, and dial painting.

Isaac Newton Youngs, a Shaker brother who lived in the Mount Lebanon, New York community, built only 14 of these clocks, yet they still stand out as a hallmark of Shaker style. Some clocks were built with a glass door below, and a few were made with glass set into the side panels. My favorite is housed in the Hancock, Mass. dwelling house and looks closer to the one I build. But you couldn’t say that mine is an exact reproduction of the 1840 versions. Furniture reproduction is a slippery phrase. joinery techniques, tooling and finishes must match the original.

I have no qualms with historical accuracy, except when it comes to techniques that may have worked in the past but are not suitable today. Wood movement is one of those areas. The Shakers did not have to deal with forced hot-air heat. We do. Shaker clock makers built their cases to fit their mechanisms. We must build our cases to fit mechanisms that are commercially available today. To me, that seems perfectly aligned with Shaker ideals.

For starters, the original clock was constructed predominantly of white pine. I chose cherry for its color, hardness and grain. Because cherry moves more than white pine does, I had to make a few dimensional adjustments to allow for wood movement of the back panel. Second, I decided to use a top-of-the-line mechanical movement, which required a small amount of additional interior space. Consequently, my overall case is a little deeper, and the back is a bit thinner. So much for historical accuracy.

The construction of both the original and my version is as simple as the spare design. I will offer several options—in construction techniques, dimensional changes and types of mechanisms—to suit the type of clock you want to build. Accurate dimensions for the original clocks (the glass door, not the panel-door version) can be found in John Kassay’s The Book of Shaker Furniture (University of Massachusetts Press, 1980) or (for the clock with glass panels in the sides) in Enjer Handberg’s Shaker Furniture and Woodenware (Berkshire Traveller Press, 1991). The version I built appears in my book, The Shaker Legacy (The Taunton Press, 1998)

From Fine Woodworking #157

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in