Biscuit Basics

Speedy and versatile, the biscuit-joinery system can handle all the joints in plywood casework.

Synopsis: Rabbet and dado joints are tried-and-true, but once the author discovered the benefits of biscuit joinery, he was hooked. Tony O’Malley explains how to use a biscuit joiner to attach face frames, build drawers and case pieces, and join miters. Also find tips on shopping for a biscuit joiner and on locating and aligning biscuits with professional results.

When I started my first job in woodworking in 1984, the biscuit joiner, also called a plate joiner, was just arriving on the shop scene. The company where I learned the trade still was using rabbet and dado joints to assemble plywood case goods. It’s a tried-andtrue system but one we abandoned forever after discovering the manifold benefits of biscuit joinery.

First, by using biscuit joints instead of rabbets and dadoes, every joint is a butt joint, which makes calculating dimensions from a measured drawing much less painful and error-prone—no more adding and subtracting to account for dadoes and rabbets. Second, biscuit joinery allows you to move a stack of freshly cut parts directly from the tablesaw to the workbench, where all of the joinery work can be done (maybe not a big deal in a one-person shop, but a definite advantage in a shop where coworkers are waiting to use the saw). Third, there’s no need for dado blades and the finicky process of getting the fit just right. Fourth, biscuit joinery eliminates the frustrating task of sliding large workpieces across the saw to cut joinery. Sure, you can avoid these last two problems by cutting rabbets and dadoes with a router and T-square guide, but biscuiting is much faster. Fifth, assembling a case with rabbets and dadoes, no matter how finely fit, always requires some extra effort to get the case clamped up squarely—the joints just seem to lean a little bit on their own. A biscuitjoined case, in contrast, almost always clamps up squarely right from the getgo (assuming your crosscuts are square, of course).

But the biscuit joiner’s usefulness goes far beyond joining carcases. From strengthening miters to joining panels, from assembling face frames to attaching them to cabinets, this versatile tool can be a major player in your shop’s lineup. As a colleague recently observed, the biscuit joiner may be the most significant tool development for the small-shop woodworker since the invention of the router.

I should point out that dovetails and mortise-and-tenon joinery remain the best approaches for solid-wood furniture construction. But the biscuit joiner can handle all of the joints in a basic plywood cabinet—from the case to the shelves or dividers to the face frame, the base molding, and even a drawer—with the exception of the door, which requires traditional joinery for additional strength.

What to look for in a biscuit joiner

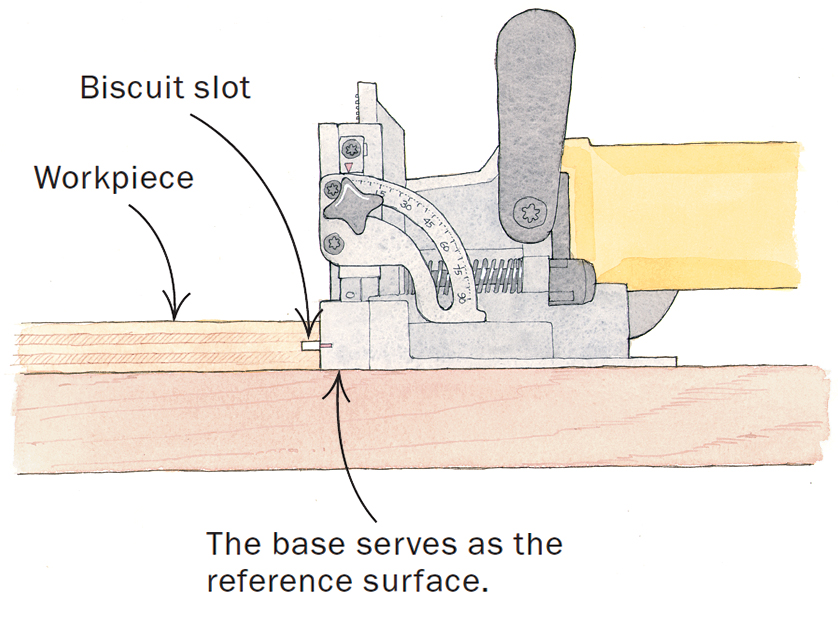

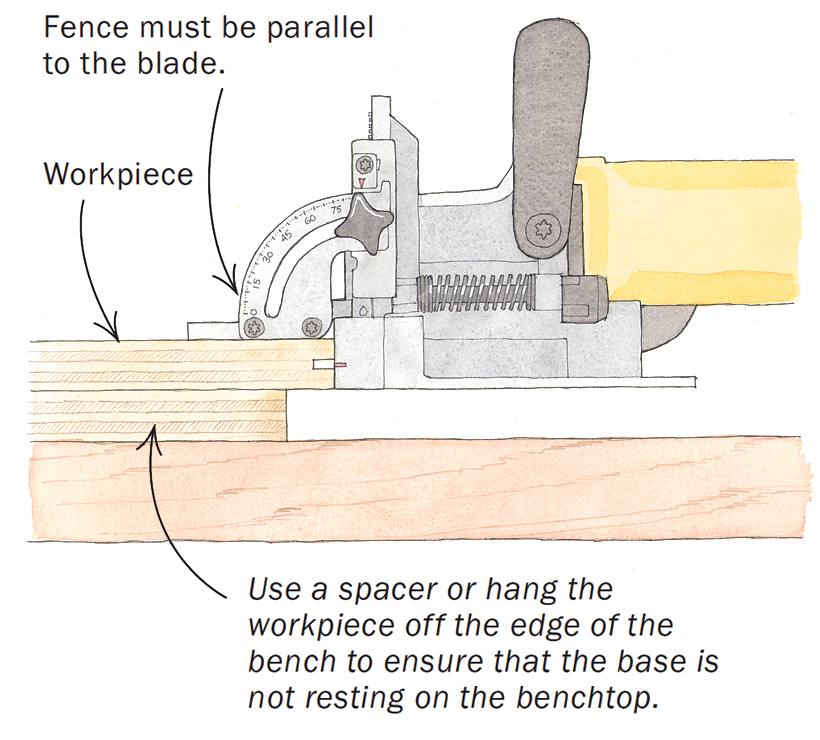

Most of the time, the base of the machine can be used as the reference surface for making a cut. In most machines this positions the slot in the center of 3⁄4-in.-thick stock. However, a fence mounted onto the face of the tool provides more versatility in positioning the slot. So it is very important that the machine cut a slot parallel to both its base and its fence; otherwise, joints won’t line up properly.

Not all machines are created equal, and it’s worth the time and effort to check that a new machine is accurate, and return it if it’s not.

Joining cases and boxes

When joining parts to form a case or drawer box, the first step is to mark the slot locations on all of the parts. Often, this can be done simply by aligning the two pieces as desired and then drawing a small tick mark across the mating edges. However, for casework, where there are several of the same type of piece—sides and shelves, for example—it helps to develop a system

From Fine Woodworking #165

From Fine Woodworking #165

For the full article, download the PDF below.

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Pfiel Chip Carving Knife

Makita SP6000J1 Track Saw

Leigh Super 18 Jig

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in