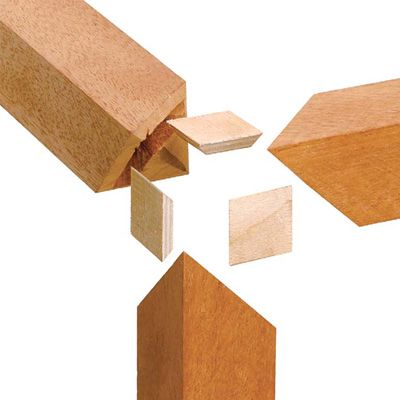

Simplified Three-Way Miter

A modern approach to a traditional Chinese joint creates striking corners on small tables and stands

Synopsis: Although there probably are a dozen or more ways to cut a three-way miter, Richard Gotz uses a method that is straightforward and relies on only a few cuts with power tools. This type of joint, which dates to the Ming dynasty, is often used in light-duty furniture and makes a striking appearance. The author calls it deceptively simple looking, but his explanations help make it seem simple to build, too.

From Fine Woodworking #169

The three-way miter is a deceptively simple-looking joint on the outside. Three equally dimensioned pieces of wood join at a corner with miters showing on three faces. One primary reason for its aesthetic appeal is that only long grain is visible; the end grain is hidden where the pieces join. While simple looking from the outside, when constructed with traditional methods, the three-way miter is anything but simple on the inside.

Complex forms of the joint, which date back to Ming dynasty furniture making, require precision cuts with hand tools. Some methods of constructing the three-way miter utilize hidden dovetails, sliding dovetails, or quadruple tenons. Because of this, the three-way miter is not often used by the amateur craftsperson. But it needn’t be so daunting. Although there probably are a dozen or more ways to cut a three-way miter, I use a method that is straightforward and relies on only a few cuts with power tools.

After attending a few weekend classes with Toshio Odate and Yeung Chan, I was inspired to create a piece of Asian-style furniture that would incorporate some of the design details they suggested. I came upon the three-way miter joint, but I was overwhelmed with the elaborate techniques involved. Just in drawing the traditional method of construction, the joint was a humbling experience; I could only imagine how difficult it would be to cut it with a handsaw and chisel.

I decided to forgo the most elaborate forms of the three-way miter for a modern method. I tried a couple described in books by Chan and Gary Rogowski, but they required several different settings on the tablesaw, with each pass needing readjustment of the miter gauge, fence, or blade height. It was clear that achieving a tight fit with either method was going to require great precision in my setup. Any inaccuracy multiplies with subsequent readjustments and cuts.

To reduce the chance of inaccuracy, I decided it would be necessary to reduce the number of individual cuts. I landed on a method in which all of the mortises are cut with one fence setting on a hollow-chisel mortiser; all of the miters are cut with one setting on the tablesaw; and loose tenons are used to join the pieces. Furthermore, the four rails and four legs that make up the basic table all are produced with the same series of cuts.

The strength of the three-way miter using this method, for the most part, relies on the loose tenons. Because the mitered surfaces of the rails and legs may not provide an adequate bond, be careful how you plan to use this joint. I would recommend it for light-duty use only. Aprons or stretchers will increase the strength, as will larger tenons.

For the full article, download the PDF below.

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Suizan Japanese Pull Saw

Drafting Tools

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in