A Short History of Shelves and Bookcases

While a case suggests a closed object, bookcases are now very commonly open fronted, and as such are often really no more than a simple series of shelves designed to hold books. Thus, curiously, the bookcase has come full circle from its earliest form as a simple shelf, most commonly integrated in the wall in the manner of early aumbries, where a medieval scribe kept the book or codex he was writing, through its development as one of the largest pieces of furniture ever made, typified by the often enormous cabinets of architectural proportions used from the 17th century to recent times and which may be thought of as the direct ancestors of the modern entertainment center.

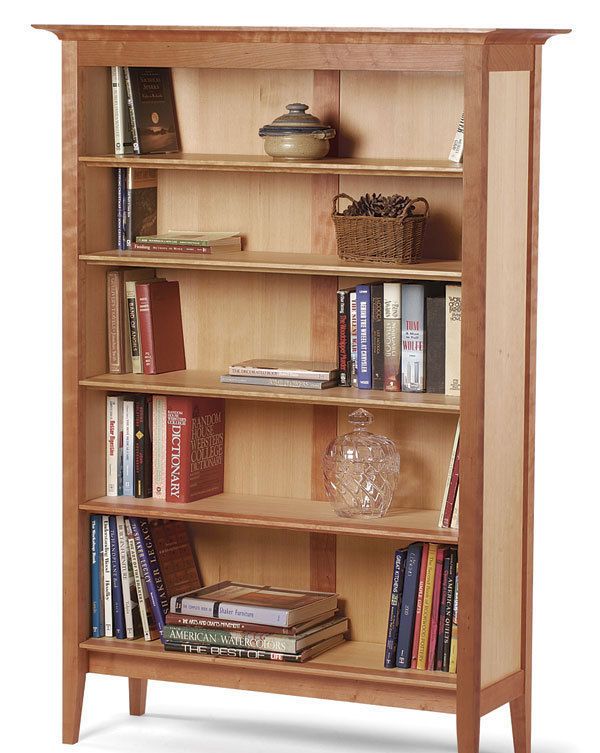

The chief difference between the medieval version and the modern bookcase is that the contemporary type is usually freestanding. Two uprights supporting two or more horizontal shelves, the whole kept rigid by a fixed back, constitutes the simplest contemporary form. Given the great variation of book sizes, shelves are often made adjustable, supported on pins or pegs inserted into appropriately spaced holes made in the insides of the uprights. Providing the shelf supports are sufficiently strong, the chief consideration of the successful bookcase builder is to use material rigid enough or of sufficiently thick dimension to resist sagging. A pine shelf, for example, needs to be made from 5/4 material if it is going to be much longer than 3 ft.

Even after the invention of the printing press, books continued to be among the most precious and treasured household possessions, and as a result bookcases, as books became more common, and as libraries increased in size, were invariably furnished with doors — becoming, in fact, cases — usually glazed so that bindings could be protected but admired. An exception was the large built-in university bookcases, the ancestors of today’s public library bookshelves. These, however, were commonly pierced for the chains which secured the books. Another distinction resulted from the fact that books were commonly shelved with their spines to the back of the case, in order to display the ornate clasps that secured the covers.

Large formal bookcases, may be made in a variety of styles, ranging from two- or three-part breakfronts, to tall cabinets with an enclosed base containing drawers or small cupboards, to smaller glass-fronted cabinets, such as the stackable horizontal form known as “lawyer’s bookcase.” For reasons of stability, given the weight of large numbers of books, bookcases designed for substantial quantities are typically made with wider, deeper, or heavier bases than the upper cases. Similarly, rather than relying on pins or pegs for shelf supports, shelves are often housed in rabbets or serrated cleats. Vertical divisions or supports also become necessary where the books are larger than normal, both to protect the books from each other as well as to provide support for superincumbent shelves.

While many bookcases are designed as built-in units, many are freestanding, and may be designed double-sided, or even as round or four-sided units, intended for mid-room placement.

Graham Blackburn is a furniture maker, author, and illustrator, and publisher of Blackburn Books (www.blackburnbooks.com) in Bearsville, N.Y.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in