The Day They Built His Box

A woodworker's life remembered through the story of his handmade cherry coffin

Early in our marriage my husband informed me, while I rummaged through a pile of lumber, to be especially careful of the cherry boards. They were for his coffin, he said. We were working out in our woodshop, located near the shoreline of Chautauqua Lake, New York; both of us working on separate projects but working together, as we always did. It was in our large and well-equipped woodshop filled with saws, planers, and a long, hand-built steam box. The walls and much of the floor covered with handmade jigs for rustic furniture construction.

But his coffin? Well, OK. My husband had strong ideas and could build just about anything. He bought the wide, clear, air-dried cherry boards from an Amish man he knew and kept them up on a rack in the back corner of the shop. He liked to visit them; pat the boards and promise them they would be given a good home. I was warned never to cut off even a little bit for a project of my own. My husband knew me well with such cautioning.

A box for many purposes

My husband, Charlie Greene, was a long-time carpenter. He would recall the “old days” when men reported to work wearing white bib overalls and shined shoes. He worked with men who built all their own tools, as a part of their training and education. A mostly self-taught man, he could build roof trusses as easily as he put together custom-made rocking chairs. He was very good with a hammer.

We discussed the actual building of his coffin after finding an ad in Mother Earth News. An Episcopal minister in California (where else?) offered sets of plans for constructing such an object; he even offered two distinct styles. Alternatively, he would sell the finished product or he could arrange for your ashes to be sprinkled at sea, should that be your desire.

In addition to plans for the box, which we ordered, he included suggestions for alternate uses while the casket sat in your home (or garage — there are wives who aren’t having “that thing” in the house). Those included a toy box, a bookcase, or my personal favorite, a wine rack. Included were detailed plans for adding these features. (I never got the wine rack. Darn.)

“It’s time to build the box”

One day Charlie, then about 75, though still out in our shop and working on one of the many hickory rocking chairs we were well known for, slowly laid down his hammer. “I think it’s time to get that box built,” he said. His face was pale and I suspected he was having angina.

One day Charlie, then about 75, though still out in our shop and working on one of the many hickory rocking chairs we were well known for, slowly laid down his hammer. “I think it’s time to get that box built,” he said. His face was pale and I suspected he was having angina.

“OK,” I agreed, “let’s stop what we’re building and start on it right now.” If he thought the time had come, then the time had come. Charlie had had at least two major heart attacks and was working in the shop, swinging a hammer and running a commercial-sized planer, while on oxygen. The fact that he was even out in the shop was a shock to many people.

But he surprised me. “I don’t think I can,” he continued. “I’ve gotten too weak. What are we going to do?”

Since this was a long-standing plan of his, I knew not to brush off his concerns. “Let’s have a family party and let them help you,” I told him. “I’m sure they would. Six or eight people. You can get it done in a day.”

He ran to the phone and called his three daughters. I remember it being March of that year; the farmers weren’t farming yet, and those that were carpenters were still off from the seasonal work. So it was a good time to get everyone together. His family was from a long line of blue-collar workers.

“We’re having a party on Saturday,” he told each of his girls. “But you’re not invited.” Not rude, just focused, that was my husband. “This is just guys. We’re gonna build my box.” He had told them this many times over the years, and I am sure they had taken that news as another of Dad’s plans — plans that would never reach completion. At least that was their hope.

“Dad, you can’t do that,” was the general tone of the phone calls. “I mean, can anyone just build a coffin?”

“Can I do this?” he asked me, getting off the phone after three nearly identical conversations, a worried look on his face. “Can I really build my box?”

“It’s perfectly legal, and yes, you can do it.” I told him. I had, on my own, visited the funeral home we planned to use and asked that very question, assuring them it would be a sturdy container, worthy of the carpenter who assembled it. Their only stipulation to me was to be sure the ‘bottom didn’t fall out.’ I assured them the bottom would not fall out of anything my husband built.

Building day arrives

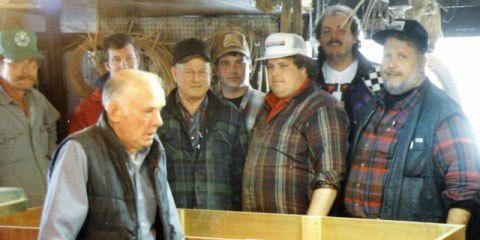

Saturday came. Men started arriving in well-used pickups until the yard was filled: a brother-in-law and his son, two grandsons, two sons-in-law, and a close friend who was thrilled to be included. My role — and I was given clear instructions — was to provide food and drink. I was not allowed to step into the shop unless on that mission. No women, the rule for the day.

Saturday came. Men started arriving in well-used pickups until the yard was filled: a brother-in-law and his son, two grandsons, two sons-in-law, and a close friend who was thrilled to be included. My role — and I was given clear instructions — was to provide food and drink. I was not allowed to step into the shop unless on that mission. No women, the rule for the day.

They carefully brought the cherry boards out of the dusty corner where they were stored and began to sketch out plans, laughing and kidding as they worked. It was a day for telling jokes and taking pictures. Someone started up the jointer and planer and smoothed the boards, taking off the roughness of long storage. Then they were brought to the tablesaw, where the boards were cut to size. I remember later, looking at photographs of the day, wondering why someone didn’t lose a finger, as every time they made a cut, at least six hands were on the board, posing for pictures.

Along the way, the running joke of the day was this: “Come on Grandpa, let’s get you in it to try it out. We gotta make sure it’s the right size.”

His reply: “Let me go get one of my guns and we’ll see who tries it out for size.”

They finished the beautiful cherry wood casket in one day, adding interior braces that came in handy later when I added shelves. But time got away from them so to make the lid, they simply used three narrow boards instead of the split top they had planned. It sat in splendor on a pair of sawhorses covered with an old, worn nine-patch quilt. I rubbed it with several coats of a hand-applied varnish and even thought to add wood plugs to cover the screw holes. This box would be a testament to a life well lived.

They finished the beautiful cherry wood casket in one day, adding interior braces that came in handy later when I added shelves. But time got away from them so to make the lid, they simply used three narrow boards instead of the split top they had planned. It sat in splendor on a pair of sawhorses covered with an old, worn nine-patch quilt. I rubbed it with several coats of a hand-applied varnish and even thought to add wood plugs to cover the screw holes. This box would be a testament to a life well lived.

Then I called the local lumberyard, looking for hardware to attach the side rails. Though we weren’t planning to carry it, we still wanted it to look like a traditional coffin.

“I’m looking for casket hardware. What do you have?” I asked.

“You know, lady, we don’t get a big call for stuff like that. I’m not real sure where you might find any.” I’m sure they thought I was joking.

“What about brass stair-rail brackets turned upside down? Would that work? We could bolt them on,” I suggested. They seemed to agree that would be the best plan, so we added rails made from cherry 2x2s, rounded on the edges. With the addition of two small quilts, one to lie on and one to cover his legs, the box was done. The quilts, made of a blue cotton to look like worn men’s work shirts, were my contribution to the day.

One day it finds its use

Several years went by. The box sat on the sawhorses in the shop, getting dusty but visited often by my husband. He would proudly show it to surprised clients and tell them how it came to be built. Some weren’t too thrilled with the thought or the plans.

Then came the day it was needed. I called the funeral home and told them to expect delivery. Where did they want it; what door? Then I called his grandson, who called his uncle, our brother-in-law. The two stopped what they were doing, drove down, and loaded the box onto a proper carpenter’s truck ladder rack for the trip to town. I firmly instructed the funeral home as to our plans.

“You are NOT to burn the box. We will be picking it up, after.” We selected a country song and had it on tape, “The Carpenter” by John Conlee, a really wonderful selection, considering the circumstances. We decorated the room at the funeral home with one of Charlie’s hickory rockers and photos of them building the box. We had a family gathering to celebrate his life.

Following the funeral, I again called the grandson and asked him to bring the box back home.

“Where do you want it, Grandma?” he asked, struggling to fit the heavy container through the shop door.

“Right back on those sawhorses,” I told him. “I’ve got a set of brass casters that I intend to put on the bottom, then stand it up and put shelves inside.” And that’s what I did. The same Amish man who sold him the lumber made me cherry shelves that fit perfectly inside.

The box held beautiful timeworn quilts for another several years. Most people who came into our woodshop-turned-studio never realized, unless it was mentioned, the origins of the beautiful cherry cupboard. And the minister in California missed another possible use for one of his creations.

Ruth Greene is a fiber artist. She and her late husband Charlie built heirloom hickory rockers in the Amish style for more than 10 years.

Top photo (pictured left to right): Ron Vondell, brother-in-law; Ken Moore, friend; Charlie Greene; Paul Mest, son-in-law; Ray Vondell, nephew; Ed Mye, grandson; Ted Ellis, grandson-in-law; George McCall, son-in-law. Photos courtesy Ruth Greene.

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Suizan Japanese Pull Saw

Comments

Very touching!

Thank you for sharing.

What a great story and legacy of something handcrafted with love.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in