A Timber-Frame Dream

Make it affordable by finding a company that recycles old barns

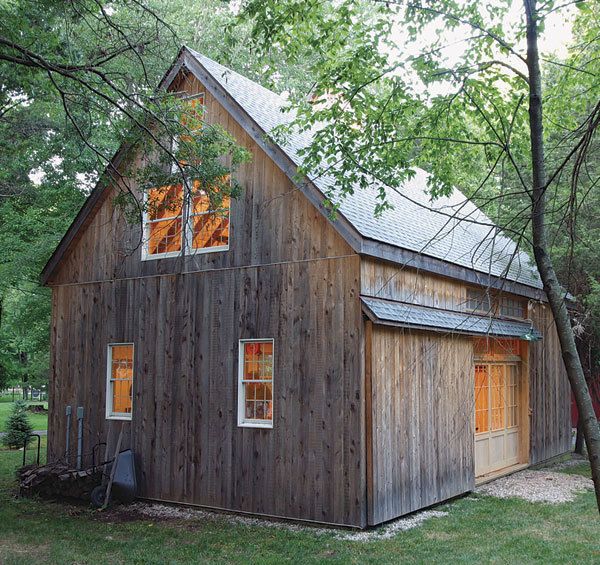

Synopsis: When Eric Foertsch set out to design his dream shop, he decided a timber-frame structure would fit in best with his Connecticut neighborhood. So he designed his 24-ft. by 36-ft. shop to resemble a 19th-century barn, and used timbers from a 100-year-old barn in the construction. Hardwood floors, wainscoting, and finished walls between the exposed post-and-beam structure give the shop the appearance he wanted, while modern insulation helps keep it comfortable. Foertsch takes readers through the process he went through to design his shop, and details some of the challenges he faced that are unique to timber-frame construction.

For 15 years I dreamed of building the perfect shop. After making do with space in cramped, dark garages and basements, I wanted a workspace that was bright and inspiring. When we moved from New York to Connecticut, I had my chance.

Designing my ideal shop building consumed the first few months of 2004. I made lists, read books and magazines, drew on 15 years of experience, and made dozens of layouts on graph paper.

I kept asking myself if the shop building would create a positive, a neutral, or a negative value for the property. In the end, I decided that a building made with conventional framing would be a neutral addition at best, but a properly executed timber-frame structure would be a positive—especially from inside, where it would be obvious that this was no ordinary structure. A timber-frame shop also would fit in with the neighborhood and would be adaptable for other uses.

Hardwood floors, wainscoting, and finished walls between the exposed postand-beam structure give the shop the bright and inspiring appearance I’ve craved. If the next owner doesn’t need a shop, the building will work as office space or as a studio.

In my experience, building a timberframe structure involves about as much time and expense as a conventional stick-frame building. The biggest drawback to timber framing is the extra time needed to get building permits and find a reputable, affordable timber framer. Timber framers don’t use graded lumber, so a building inspector may require a structural engineer to provide a set of plans that include all the necessary load and span calculations.

Setback requirements for local zoning restricted me to a 24-ft. by 36-ft. structure. With its second-floor loft, the building has 1,500 sq. ft. of floor space. That’s large enough to satisfy my main requirement: being able to work with plywood sheets anywhere in the shop. Still, I couldn’t make space for a finishing room or a dedicated place to dry wood.

Before I could proceed, I had to gain the building inspector’s approval. I used Tedd Benson’s book Building the Timber Frame House (Fireside, 1981) to provide tables, charts, and stress calculations for every joint and beam. It helped to over-engineer the design. If you’re not up to dealing with the local building department, be sure that the timber framing contractor you hire can obtain needed permits and variances.

Getting real

Internet research turned up companies that would build a brand-new timber frame, but they were way too expensive—about $45,000 just for materials. That’s three times the cost of conventional stick framing. My best option seemed to be a company that could dismantle, repair, and reassemble a timber frame on my property. Their prices came closest to fitting my budget.

From Fine Woodworking #188

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in