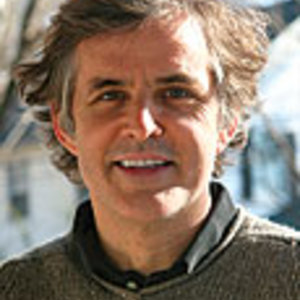

Talking Shop with Brian Boggs

The celebrated chair maker talks about the history and future of his collectible ladderback chair

Brian Boggs has roots in Kentucky that predate the Revolution, and so do his chairs, which are descended directly from Appalachian post-and-rung greenwood chairs. He was studying French and philosophy at Berea College in Kentucky when he dropped out to become a woodworker. Today, embracing the Appalachian tradition but infusing it with new energy, Boggs creates some of the best chairs made. Crafted from hand-picked veneer-grade logs, with hand-harvested hickory bark for the seats, his ladderbacks are an extremely rare combination of strength, style, exemplary craftsmanship, light weight, and real comfort.

|

See a complete list of articles and videos from Brian Boggs. |

I spoke with Boggs in Berea at his shop, at his house, and on a nearby stream while we fished for bluegill.

Jonathan Binzen: Did you have particular experiences when you were young that drew you into woodworking?

Brian Boggs: I didn’t really have any experiences growing up that were related to woodworking-other than whittling on a stick with a knife, and that wasn’t very inspiring. I took one shop class in junior high school, but I absolutely hated it.

JB: What did interest you in those days?

BB: Art. I got interested in second grade and stayed with it. After high school all I wanted was to be a painter. There was no Plan B. I bought a one-way ticket to France and stayed there on my own for most of a year traveling and working. Everybody I met and everything I saw was amazing; I had a real eye-opening adventure.

When I came home I tried to paint that experience. But I couldn’t do it. I couldn’t come close to making what I was feeling happen on canvas. I had never attempted to paint totally from what was inside, and I got completely frustrated and finally just gave up. I realized that art was a place for a more vivid imagination than mine. It was very hard to let that go.

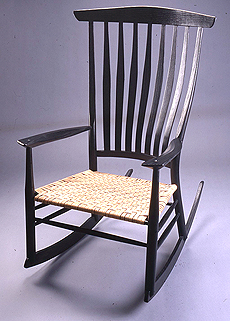

Trademark chair. It took many years for Boggs to settle on his classic ladderback chair design, which descended directly from Appalachian post-and-rung greenwood chairs. See it in The Gallery.

JB: So what led you toward chairmaking?

BB: Eventually I started opening up to other ideas, and at that point I ran across some Fine Woodworking magazines. They gave me my first glimpse into the potential of furniture as something expressive or something artful. I had never looked at it that way.

Then I took James Krenov’s books out of the Lexington library and they got me excited about everything related to woodworking. I could feel gears were turning–suddenly I knew I had to do this, this is where I’m going to go.

JB: But at that point you still hadn’t done any woodworking?

BB: I hadn’t even met a woodworker. My exposure was just through books and magazines. But it seemed to me that what had attracted me to art could find a really good home in woodworking the way Krenov looked at it. The one obstacle was money. I didn’t have any and I figured setting up a shop was going to cost $10,000.

Then I saw John Alexander’s book on greenwood chairmaking: Make a Chair from a Tree. Even though the picture on the cover–of a simple post-and-rung chair–was not at all like anything Krenov was talking about, I saw the two together. Everything Krenov was saying in his book seemed like a possibility within this other craft of chairmaking. Even today, though you might not see any obvious Krenovian influence in my chairs, it’s definitely there.

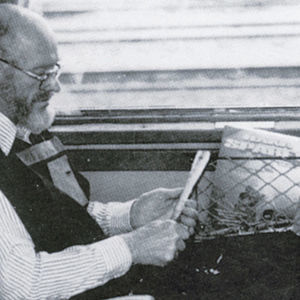

The workhorse. The spokeshave is one of Boggs’s favorite tools for shaping chair parts. He has even designed his own spokeshave distributed by Lie-Nielsen Toolworks.

JB: What appealed to you about Alexander’s book?

BB: His whole method seemed very approachable. Every step from the raw log to the finished chair was accomplished with hand tools. I liked the fact that it was physical, it was art, it involved wood and tool making–and it was cheap.

JB: What do you remember about making your first chair?

BB: I had decided to make a chair like John Alexander did. My wife and I were driving along and I saw a log on the side of the road, five feet long and perfectly straight. I thought it was oak. The landowner said I could have it, so I put it in the trunk of the car and drove home. I split it out and made a chair out of it. Turns out it was sassafras, and the chair didn’t hold up that well because it was too soft. But it was great wood to learn on–easy to work, easy to split, quick to dry.

On that chair and several afterwards I made mortises with a sharpened screwdriver. I literally didn’t have money for a chisel. We were that broke. I didn’t have a grinder, so I filed the screwdriver sharp–I was going to get to be a woodworker no matter what.

At home with machines. Boggs rehabbed this vintage bandsaw and uses it with templates to quickly rough out the profiles of chair parts.

JB: How well did the screwdriver work?

BB: It made a hole. And it didn’t take that long. You hit it with a hammer and it’d go into the wood, but it wasn’t real clean. I would use a block-plane blade to pare the sides of the mortise. It sounds pretty Neanderthal, but it’s really not such a bad thing. Once you understand how a chisel works, you can make one out of just about anything–the end of a file, or whatever. But I admit it’s nice to have a good chisel.

JB: What other tools did you have at that point?

BB: It’s a short list. Along with the screwdriver, I had a brace and bit, a hatchet, a really crappy little block plane. I bought a froe and made a maul for it. I picked up a drawknife for three bucks at a flea market. I couldn’t afford a spokeshave, but my grandfather mailed me a check for twelve dollars so I could buy one. And I built a shaving horse out of fencing planks from my dad’s farm. It was an awful horse. Absolutely awful. It was a $50 shop.

JB: You’ve always had a strong interest in tools, not just furniture.

BB: Reading Krenov’s books, I was as turned on by his talk about making handplanes as I was by anything else. Soon after I got my first spokeshave I started trying to make it work like a Krenov plane. At first I worked at making a good spokeshave out of a bad one. Eventually, I designed and made my own spokeshaves. There’s no lack of creativity in that kind of work.

Engineering the process. Boggs has produced a form for bending each thick chair leg that is steam-bent into a difficult double-curve. Much of his process relies on innovative jigs and fixtures.

JB: For someone who was weaned on a pure hand-tool method, you have quite a well-equipped and jigged-up shop these days.

BB: For a long time I did everything by hand, and I developed a pretty rigid philosophy about the superiority of greenwood joinery and hand techniques. But I gradually became more open minded.

JB: What led you to start introducing machines?

BB: For one thing, ladderback chairmaking requires a whole lot of spokeshaving, some of it pretty heavy, and my back started to feel it. I realized I needed a better balance of activities in my work.

I also realized I didn’t want to work alone anymore. And once I’d had a few employees that didn’t work out, I began to see that you have to have power tools and good jig systems in order for an employee’s work to be profitable–for them and for you.

And about eight years ago, when I found myself avoiding some design directions because of the difficulty of doing certain joinery by hand, I started routing my mortises.

Built to work. Boggs has devised several machines and jigs to speed up the custom process, like this one for drilling precise mortises in chair posts.

JB: I noticed that you sign and number all your chairs.

BB: I do. I used to think it would be arrogant to sign my chairs. Part of me wanted to be an anonymous chairmaker living out in the country. I thought a handmade chair should be worth something because it’s a good chair, not because somebody made it who’s trying to get a name for himself. But I came to think that signing the chairs could be meaningful to the person who bought them. I think the things you surround yourself with have a real impact on you. And when you have things that are made by people you know, or people you’ve met, there’s a connection there that’s almost like a connection of soul.

I still like the idea of the anonymous craftsman, and I like the fact that my chairs are derived from of an old local craft. A lot of the techniques I use are different, but I feel I’m carrying through the spirit of that old tradition.

JB: How does the design of your ladderback chair relate to traditional Appalachian chairs?

BB: The ladderbacks I make now are essentially an Appalachian chair molded to fit your body. And modified with a splay in the legs for stability. I made Windsor chairs at one point and liked the splay in their legs for mechanical and aesthetic reasons, so I imported that to my ladderbacks. The seat frame I use is an adaptation from country Chippendale chairs with rush seats.

Bent for comfort. Backsplats dry in a rack that forces them into anatomical alignment.

JB: When did you design your ladderback?

BB: The design evolved from day to day and year to year for a long time, but about 10 years ago it reached a point where I was satisfied with it, and I’ve been making it pretty much the same way since.

I thought through every aspect of the chair and made sure every detail was justified on the basis of aesthetics, structure, and comfort. Even down to the finish. The spokeshave finish is efficient, but also adds a kind of comfort. When your fingers run across all the tiny facets of a shaved surface it feels good in a way that a sanded surface doesn’t.

The splay in the back legs below the seat makes the chair more stable, since it’s not going to tip over; it makes it stronger because of the angle; and makes it look more balanced.

Even the little slat pins serve several purposes. They help lock the slats in place, but they’re also one of the first visual details that people pick up on. They’re carved to a little pyramid, and that’s partly for looks, but it also keeps the corner of the pin from catching on your clothes.

JB: Your chairs have one foot in the past and one in the present. Where does that put you in terms of the contemporary studio furniture scene?

BB: I don’t know if what I do is studio furniture or not, but I like to think of this as a chair shop rather than a studio. I am producing my ladderbacks from a design I stopped working on 10 years ago. The studio furniture maker for the most part does not want to be stuck in this position. But to me this isn’t stuck at all. This is freeing.

Reproducing the same design over and over develops skills. And unless you get into production work and have a chance to study the process it’s impossible to get truly fluid in the work. Some people make a living building three pieces a year, and they do fantastic work. But I’d rather be the guy making a houseful of chairs for somebody.

His other signature piece. Boggs’s deep-dish rocking chairs are a natural extension of his side chair design.

JB: With the ladderback design worked out, where do you put your creative energy?

BB: I work on other designs. And I pay more attention to making the whole process from log to gallery more fluid. At one level, designing a chair is about aesthetics and ergonomics, but at another level it’s about what kind of situation the chair is going to create as it goes through the shop-it also needs to be beautiful there. It takes a lot of logistical creativity to make the construction process flow in an efficient and enjoyable way. I find that challenge quite rewarding.

JB: Is your work as satisfying as it was in the early days?

BB: Tooling up certainly hasn’t taken the romance away. I have more design options than ever before and I’m still learning as much every day as I did in the beginning. Satisfying is just too light a word. I’m as starry-eyed as ever. It feels like there’s almost no part of me that isn’t stimulated by doing this.

Jonathan Binzen is a freelance writer and former editor of Fine Woodworking.

Photos:Jeff Carr

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in