The Art and Craft of Room Screens

The range of uses is exceeded only by the design possibilities

Synopsis: Room screens are useful for sectioning off parts of large rooms, and are also a natural choice for screening bright windows or cluttered areas. The simple frame-and-panel format allows a room screen to be filled with striking veneers or solid wood, light-filtering handmade paper, works of art, or anything else that can be adhered to a flat substrate. Jonathan Binzen’s article showcases the work of several screen designers–Craig Vandall Stevens, Joe Tracy, and William Laberge–illustrating such techniques as using precision-cut dividers and gridwork, light construction for sliding screens, and using solid panels. He also details how to choose the correct hinges, whether single acting or double acting.

Room screens stand in a category of their own. They’re not quite furniture, since you don’t actively use them and rarely touch them; and they’re not quite millwork, since they’re freestanding and movable. Their closest cousin is the door, with which they share hinges and a frame-and-panel structure. But you can’t slam a folding screen or close one against cold or noise. Lightweight and a little lonely, they are designed simply to stand there and look pretty. With the right screen, though, that’s enough to transform the whole flow and feeling of a room.

Screens are particularly useful for dividing space in the large, open-plan rooms of contemporary houses. A screen might be used to carve off an area for a home office, to screen off a passageway or an entry and make a sitting area cozier, or to make a meal more tranquil and intimate by hiding the mess in the kitchen.

With its frame-and-panel format, a screen is essentially a frame waiting to be filled— with striking veneers or solid wood; with light-filtering handmade paper; with works of art on cloth, canvas, or hardboard; or with anything else that you can adhere to a flat substrate. The screens that follow provide a sense of the wide range of materials and formats available to the imaginative screen maker.

I’ll also describe the different ways to engineer a screen—single or multi-section, self-standing or with feet—and detail the range of specialist hinges for screens. Building a screen is as straightforward as making a lightweight door, but with lots more ways to display your creativity.

Translucent Screens – Precision-cut dividers provide the artwork

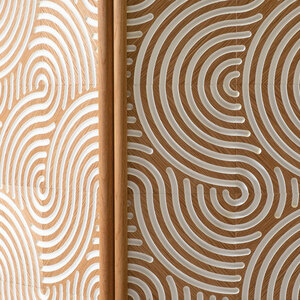

Taking his cue from traditional Japanese shoji screens, Craig Vandall Stevens, a furniture maker in Sunbury, Ohio, uses softwoods such as cedar, cypress, and white pine for his screens. These woods are light both in weight and in color; they also plane beautifully, making the exacting joinery easier to accomplish. To make these curved-gridwork doors, Stevens used one large plank of perfectly clear Eastern white pine, which yielded impeccable uniformity of color and grain throughout the piece.

The gridwork has its own thin frame, to which the interior pieces are joined with half-laps. When the gridwork is fully assembled within its frame, the whole is press-fit into the outer frame. All the joints in the gridwork are half-laps, including those that hold the slender curving vertical members. The curves were created simply by nesting a pair of slender pieces in the same notches at the top and bottom and then separating them at the center rail.

As on most traditional shoji screens, all the parts of the frame and the grid lie in the same plane on the back so that the paper can be applied directly over all of them. For more on making a screen backed with Japanese paper, see Master Class on pp. 96-100.

From Fine Woodworking #191

For the full article, download the PDF below:

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Compass

Stanley Powerlock 16-ft. tape measure

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in