Culture Clash

Two master wood turners produce very different 'Oriental' bowls

PORTLAND, OR.–I recently spent most of one morning shuttling between two similar yet totally different demonstrations at the American Association of Woodturners Symposium here.

The convention, which picks a new host city each year, always has dozens of well-known turners teaching their special techniques. This year, the turners included two master craftsmen from Japan. They were here to explain techniques of traditional urushi lacquer finishing.

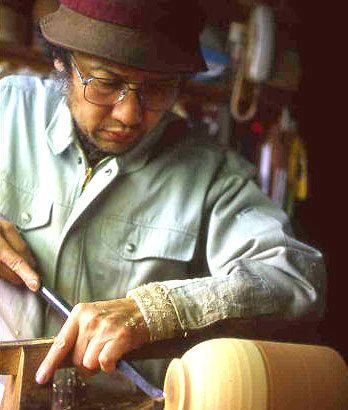

As it happens, Yasuhiro Satake was demonstrating urushi at the same time that Jimmy Clewes, a master turner from Britain, was showing his audience how to make one of his signature pieces, an “Oriental lidded box.” I couldn’t resist moving from one demo to the other to draw comparisons. (Above, master turner Yasuhiro Satake completes a bowl for urushi lacquer using a tool he made himself.)

Gear shifts

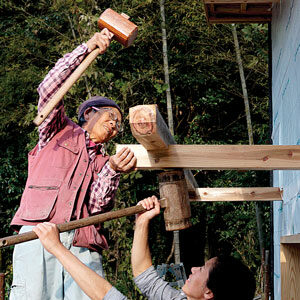

The two Japanese craftsman set up a Japanese lathe to accommodate their demonstration. About all it has in common with a Western lathe is a motor and a drive belt. The bed is a simple wood table pushed up against the headstock. The toolrest is a rude-looking wood trestle that rests on the table. The speed control consists of two foot pedals, which operate levers that push drive belts on or off of pulleys. The operator can stop or reverse the lathe’s direction almost instantly. The top speed is 600 rpm.

The chuck consists of a thick block of wood attached to the drive spindle and dotted with a half-dozen nail points. The workpiece is tapped onto the nails, which hold it fast. It’s efficient and ergonomic. Satake pulls up a stool and sits to work. His tools are ones he forged himself, typically a shaft of carbon steel and a hook-shaped cutting tip made of high-speed steel and brazed to the shaft. A bucket of waterstones sits at the ready when one of the oddly shaped cutters needs sharpening.

Meanwhile, Clewes stands at a Oneway 1640, a Canadian lathe that’s widely regarded as one of the best makes. It’s made from thick slabs of sheet metal, with a hefty steel tool rest and a large scroll chuck. Top speed, 2,600 rpm.

His tools are the Western gouges, skews, scrapers, and parting tools. He keeps all well-sharpened on a bench grinder.

Real Japanese vs. Oriental inspiration

The Urushi process

Urushi bowls are rough-turned from green wood, dried for almost four months, then finished.

It takes Satake only a few seconds to clean up the outside of the bowl and to incise it with one of several traditional textures. A hacksaw blade, ground thin and grooved at the end, makes the grooves.

Like other Japanese turners, Satake balances the tool on the rest so that it touches the work from below. He also reverses the lathe’s direction frequently, the better to reach certain parts of the piece. Urushi finishes up with a very sharp piece of hacksaw blade, using it like a cabinet scraper to make the wood perfectly smooth. It gets no sanding.

Back at the OneWay

Clewes begins his demonstration by winding a 10-in. by 4-in. length of maple onto a screw chuck, then cranking the lathe up to its top speed. The wood moves and sounds like an aircraft propeller. You can see only the smallest part in the center of the piece. The rest is a big loud blur.

Unfazed by the sound, Clewes takes a fingernail gouge and deftly curves the face of the maple, giving it a shallow arch shape. The ends of the arch become what Clewes calls “wings” that support the middle of the piece. He turns a small hemispherical bowl in the middle and, once it’s smoothed, covers the bowl in gold leaf.

After that, Clewes remounts the piece and turns the wings thinner. He then chucks on a smaller maple blank and makes a nearly identical shape that becomes the box lid.

Final products

In the end, Satake and Clewes produce beautiful, distinctive pieces.

The finished urushi bowl, with walls a uniform 1/8-in. thick, is unmistakably Japanese in its shape, its proportions, and its textures. It epitomizes traditional Japanese craft. Afterward, Satake tells me through an interpreter that he enjoys a challenge and will occasionally make a tool that differs from the traditional cutting shapes. And one of the translators tells me that Satake has a reputation as something of a rebel because he insists on making one-of-a-kind art turnings in addition to traditional shapes.

Satake holds an edikove, a small platter used in the Japanese Tea Ceremony. The piece is only 1/32 in. thick. Photo David Heim.

After his demonstration, Clewes tells me that he draws inspiration for his bowl from the flared shape of samurai helmets and the distinctive eaves on roofs in Japan. However, the bowl has only a fleeting connection with the Orient. It’s more a good example of cutting-edge Western turning. It requires considerable skill and a steady hand to turn a rectangular piece of wood. And the finished bowl keeps its rectanglar shape, so it isn’t immediately apparent that it’s been turned.

-David Heim is an associate editor of Fine Woodworking.

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Compass

Sketchup Class

Drafting Tools

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in