Poetry on Wood

Indian craftsman uses ancient pierced-stone carving patterns on wood and furniture

Mohammad Matloob is an award-winning furniture maker in East Delhi who is helping to keep the ancient jaali carving tradition alive. In Hindi, jaali means gauze, sieve, or any piece with holes to allow air or water to pass. Intricate jaali ka kaam, or very fine trellises, have their origins in Mughal architecture and are featured in buildings like the Taj Mahal. The lacy elements were ideal for windows and screens because they shaded sun but allowed air to flow.

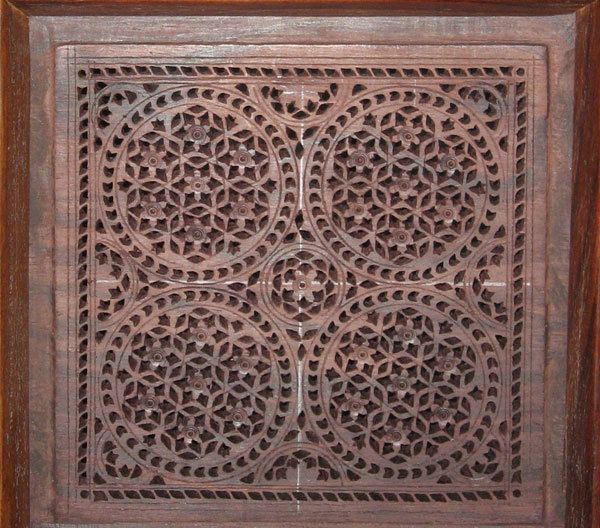

Artisans transferred the ornate patterns from stone to other materials, such as ivory and wood. Matloob applies the ancient art to boxes, benches, and other wooden forms, such as the screen shown below.

Ebony partition screen. 28 panels make up this screen. Its intricate jaali use a traditional six-floret pattern.

Matloob was virtually born in to the jaali craft and trained in it since childhood under two Ustads, or masters. One, his uncle Abdul Rehman Khan, won the National Award for Master Craftsmen from the Indian government in 1978. Matloob began working on his own in 1980 and received his own National Award for Master Craftsmen in 2005. Now in his forties, Matloob works with his brother and trains students under an Indian government initiative. He sells his work through art galleries, craft shops, embassies, and fairs.

Handmade tools, much handwork

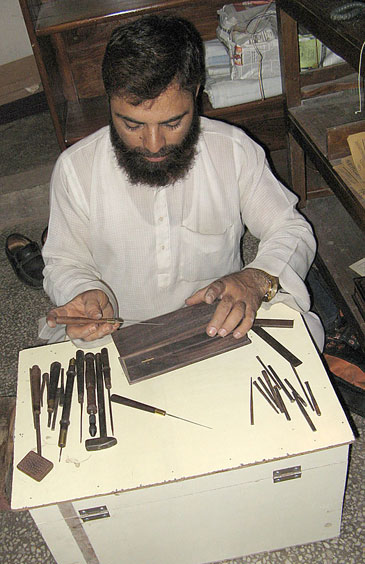

Jaali artisans create their patterns with chisels, files, mallets, and other hand tools. They generally use store-bought blades, but make most tools themselves. Matloob crafted one of his tools from the metal rib of an umbrella, for example.

Tools of the trade. A range of Maltloob’s handmade tools.

Power tools and machines, only recently introduced to the craft, are still rare. “During my uncle’s time, fewer machines were used,” Matloob says. “Today we have incorporated them to increase the speed of work.” He has learned to use an electric drill, but only for tiny holes. Otherwise, he bores holes with a burmi kamanak, a tool made only for jaali.

Matloob works at a small portable bench called a tiya. It can be placed on a larger bench, but Matloob says he can’t work when standing, or sitting in a chair. He has to spread his work on the floor.

Workbench/tool box. Maloob works while seated in front of a tiya.

Patterns as poetry

The preferred woods for fine jaali are sandalwood, rosewood, and ebony. Matloob buys wood that’s the equivalent of 8/4 stock. For his furniture, he cuts the wood to size with a pull saw, then hand-planes the surfaces. He makes the jaali panels from thinner stock.

Traditional craftsmen thought of the jaali as poetry on stone or wood. As Matloob says, “we write the pattern.” To do that, the artisan draws squares on the wood to block out the design he’s envisioned. In his work, Matloob works out the design and its points with an indigenous system of calculation, similar to metric measurements. The terminology is part of Indian woodworker lingo, fathomable only with difficulty to an outsider.

Detail work. White etchings, left, form the basis for the intricate patterns.

Once the artisan has written the pattern, he drills starter holes for the carving. He then uses his various hand tools to shape the holes to create the patterns. It’s more like working a graph pattern on wood. Jaali work is so detailed that a screen could easily take two people two to three months to make.

Many ancient jaali patterns have been lost over time, while others survive. Matloob uses six or seven patterns passed down to him from his teachers. He also created his own pattern. using it in a piece combined with inlay that won a UNESCO seal of excellence award in 2006.

Incorporating panels into furniture

Jaali artisans use a type of frame-and-panel joinery called chool to incorporate jaali panels into pieces like those shown here. The panels rest in grooves called jheeli, held in place by handmade pegs that don’t show on the outside.

Old-fashioned teak settee. One jaali panel graces the back of this traditional settee.

To finish his pieces, Matloob sands them by hand three to four times, then applies a wax polish. For jaali panels that are strictly decorative, Matloob leaves the wood its natural color. When he incorporates jaali into furniture, he uses an indigenous polish containing a pigment.

Balasubramaniam is a freelance writer based in New Delhi, India.

Photos: Chitra Balasubramaniam

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Suizan Japanese Pull Saw

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in