The Marquetry Artists of Essaouira

Some of the world's finest marquetry is created by hand in cubbyholes on the ramparts of a seaside town in Morocco.

Essaouira is Morocco’s most likeable seaside town, with a colorful dock of working fishermen, fresh sardine grills, whitewashed and blue-shuttered houses, and feathery Norfolk pines. Dark, narrow rooms beneath the town’s medieval ramparts originally stored ammunition. Later, they housed donkeys and goats. Now, the cubbyholes are home to the finest marquetry artists in the world.

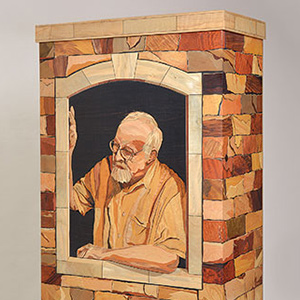

Known as the Skala de la Ville, or woodworkers souk, the area houses workshops that are piled high and stuffed solid with intricate inlaid wooden items. There isn’t even enough room for a chair. If the piece is any larger than the cramped space, the artist takes it into the street to set it on sawhorses. The sunny street is fair game for any artist needing to stretch out. It also draws customers and admirers.

Cramped quarters. One of the many workshops in the woodworkers souk in Essaouira.

The artists’ specialty wood is from the Thuya tree, a highly prized wood with a delicious perfume and found only in this part of Morocco. Thuya is a very dense mahogany-like hardwood. The most prized part of the tree is the gnarl, a rare, excrescence streaked and speckled with brown and pink, saved for the finest work. Thuya is endangered. The woodworkers use plantation-grown timber and face prison if they’re caught harvesting the 150- to 250-year-old trees illegally.

The artists at work Most pieces are inlaid with ebony, walnut, and citrus wood. The artists also use mother of pearl, threads of silver, copper and aluminum, and slivers of camel bone. Islamic artists do not use any representational figures in their art, except for trees, vines and flowers. Moroccan marquetry artists rely heavily on geometric schemes to create their amazing patterns.

Most pieces are inlaid with ebony, walnut, and citrus wood. The artists also use mother of pearl, threads of silver, copper and aluminum, and slivers of camel bone. Islamic artists do not use any representational figures in their art, except for trees, vines and flowers. Moroccan marquetry artists rely heavily on geometric schemes to create their amazing patterns.

I visited a family of woodworkers–two brothers and a son–who took turns working in the dark cubbyhole and out in the street. The father was aggressively planing a large wooden panel by hand. Inside the shop, we watched his brother work on a serving tray.

He cut a channel for inlay, smoothed its sides, then selected a tiny piece of contrasting wood from a plastic cup to fit the cavity. He filed the tiny edges, dotted the cavity with white glue, placed the contrasting wood over the channel, then whacked it with his mallet until it was flush. In the course of a week, he can create four to five such trays from start to finish.

He cut a channel for inlay, smoothed its sides, then selected a tiny piece of contrasting wood from a plastic cup to fit the cavity. He filed the tiny edges, dotted the cavity with white glue, placed the contrasting wood over the channel, then whacked it with his mallet until it was flush. In the course of a week, he can create four to five such trays from start to finish.

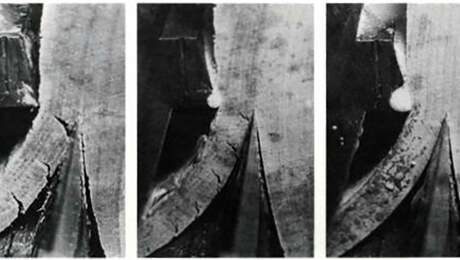

The few hand tools that the woodworker showed us were all handmade. They appeared to be hand-crafted from scrap metal; then sharpened into chisels and gouges (see photo).

The few hand tools that the woodworker showed us were all handmade. They appeared to be hand-crafted from scrap metal; then sharpened into chisels and gouges (see photo).

An apprentice marquetry woodworker begins his education in the craft when he is about fifteen years old. The training continues until he’s about 19. Traditionally, men handle the artistically skilled parts of the work, from the construction of the piece to the decoration. Women and children sand and polish the finished items. They give the wood a high sheen by rubbing it with methylated spirit and gum Arabic. They also apply linseed oil to feed the wood and prevent it from cracking.

The artisans’ co-op

Until the 1950’s, every individual artist had to venture into the forest, harvest his own trees, transport them by donkey, and hand-saw the logs into boards. But in the 1950s, a French man created a co-op for the artists in a walled-in part of the city called the Medina. Ten woodworkers can work in the co-op shop per day. The rest of the time, they are in their cubbies in the Skala de la Ville. The co-op also has a showroom for the artists.

The co-op’s central courtyard (see photo) gives the artists room to maneuver large pieces of wood. Off to the sides are large power tools, but on the day I visited only a massive, 12-ft. high bandsaw with a 4-ft. throat appeared to be working. The rest were in pieces.

On a workbench at the co-op sits a silver teapot and a small glass of mint tea. It is drunk frequently throughout the day, with four cubes of sugar in each glass. But to the woodworker, as to every other Moroccan, tea time is nearly sacred.

While a Moroccan woodworker takes a break with his tea glass, a donkey arrives with a fresh load of seven rough-hewn, 4-ft.logs. It is enough raw material, I am told, to supply one woodworker for three to four months. They will be resawed on the bandsaw and made into boards, which the woodworker can easily transport back to his shop.

The marquetry woodworkers are in good company in Essaouira, which has grown into quite an artist’s center for painting and sculpture. Many of the artists have made a name for themselves in both Morocco and Europe. You can visit the co-ops to get a fair idea of prices before venturing into the actual artist’s workshops. However, the marquetry work does not reap in truckloads of dirhum (Moroccan currency) for the artisans. Their pieces are remarkably inexpensive, especially if you buy directly from the artists themselves, down on Essaouira’s ramparts. In our visit, we bought a half-dozen small boxes for $3 to $5 each.

Photos by: Cindy Ross

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Whiteside 9500 Solid Brass Router Inlay Router Bit Set

Bahco 6-Inch Card Scraper

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in