Weekend Project: Build A Craftsman Wall Cabinet

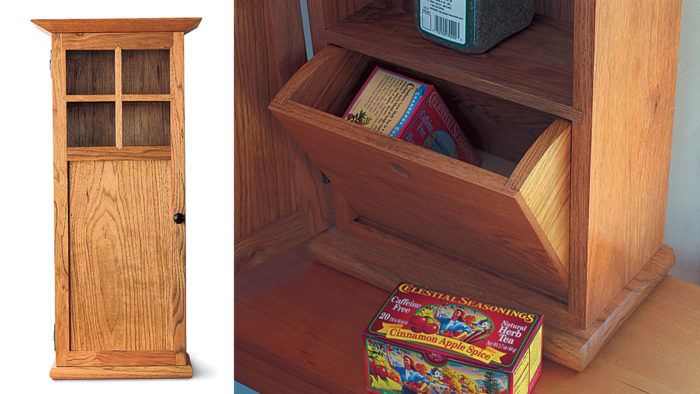

Modeled after a clock, this piece fits well in almost any tight, vertical space.

CLICK HERE to download the free plan

There is always a spot for a wall cabinet, especially a small one. This piece, a little more than a foot wide, is made of butternut, an underused, medium-toned wood that works easily.

Because this cabinet was destined for a kitchen, I outfitted the inside to accommodate spices, but the same-sized cabinet could hold anything from pottery to small books. The shelves, in this case, are spaced to fit off-the-rack spice bottles, with the bottom shelf roomy enough for larger, bulk-sized decanters. The tilting drawer at the bottom is made to fit large packages of tea.

When it comes to construction, the simplest answers are often best. On this small, vertical cabinet, I could have dovetailed the case, but I saw no need to spend the time when countersunk and plugged screws would do. And on such a simple piece, I didn’t want anything to detract attention from the door, where I spent most of the design and construction energy.

I used a flat panel at the bottom of the door to cover the drawer and bulk items, but at the top I installed glass to show off the nicer-looking spice bottles and to make the piece a bit more interesting. Over the single piece of glass, I installed muntins, giving the appearance of two-over-two panes of glass.

Begin by milling up the lumber: The top and bottom are 1 in. thick; the sides, door rails, and stiles are 3/4 in. thick; the drawer parts are 5/8 in. thick; the back and shelves are 1/2 in. thick; the muntins and door panel are 1/4 in. thick.

Building the Basic Case

Don’t waste energy with overly complex methods of building the case. Use 3/4-in. and 1/2-in.-thick stock and trim everything to width and length on the tablesaw. Set up the tablesaw to cut 1/2-in. dadoes for the shelves. Use a stop on your miter gauge to ensure that the dadoes in the back and sides will line up. It’s not really necessary to dado the back panel for the shelves, but doing so eases glue-up.

The first step in the process is rabbeting the top and bottom–because the same stop location can be used for each–on all three pieces. Then locate each shelf and set the stop on your miter gauge. When the dadoes have been cut on each of the three pieces, they should all line up perfectly. On the two sides, use the same setup to cut another 1/2-in. dado, inset 1/2 in. and 1/4 in. deep, to house the back panel.

With the dadoes lined up on the back and sides of the case, trim all of the shelves to width and length and install the 3/8-in. drawer stop on the bottom shelf. Locate the position by marking off the width of the drawer front, then inset the stop another 3/16 in. A screw holds the stop in place and allows it to pivot.

On the bottom shelf, cut a 1/4-in. by 1/4-in. groove with the dado setup on the tablesaw. This groove will work as a hinging mechanism for the tilting drawer. With the drawer stop installed and the groove cut, you can glue up the case, which should go smoothly on such a small piece.

Installing the Top and Bottom

Making the bottom of this case out of 1-in.-thick stock gives the piece a grounded look. Just remember to leave a 1/2-in. overhang on the front and sides, and make sure you account for the door. Rout a 1-in. bullnose on the edges of the bottom and leave the decoration for the top.

The treatment for the top is one I regularly use on tabletops. It lends the piece a nice, finished look and helps draw your attention to the glass panels in the door. Start by cutting a 1/4-in. bead on the outside edge at the front and sides. Then establish the overhang, in this case 1-1/2 in., and mark a line there. If it feels safe, use the tablesaw. With the piece held upright, sight down the raised blade and adjust the angle until it enters at the bottom of the bead and exits at the overhang line. You can achieve the same results by cutting to the line with a handplane. The result is a rounded top edge that angles back sharply toward the case. Both the top and bottom are simply screwed onto the case and pegged.

Building the Drawer

When you open this case, the drawer at the bottom is a nice surprise. Instead of sliding as a normal drawer would, this tall drawer tilts forward and down so that you can reach in for tea or whatever you decide to store inside. The sides and back are rounded so that the drawer slides open easily with the pull–nothing more than a 3/4-in.-dia. hole in the front–but the stop keeps the drawer from falling out on the floor. By twisting the stop you can easily remove the whole drawer for easy cleaning or restocking.

The four sides of the drawer are cut to size and dadoed with a 1/4-in. blade to accept the plywood bottom. Make sure you cut the front wider so that there will be enough material to form the pivoting bead along the bottom. The two sides and back are all shaped on the bandsaw, and a small notch is removed from the top center of the back to allow for the drawer stop.

To provide the tilting action, the bottom of the front of the drawer has a 1/4-in. bead that protrudes down into the groove cut into the bottom of the case. Rout this bead on the inside of the drawer front, then use a dado blade to remove the front edge. This bead should fit nicely into the groove on the bottom of the case and allow the drawer to fall forward.

The drawer is glued up with the bottom floating in the dadoes, and a few brads in the sides and back hold everything in place.

Building and Glazing the Door

The bulk of the work on this small piece involves the cabinet’s natural focal point: the door.

First, cut the rails and stiles to 1-1/4 in. wide and trim them to length. Use bridle joints to frame the door. Bridle joints not only offer plenty of strength, but they also make easy work of measuring. Because the tenons run the full width of the door, simply mark the length of each piece off the case itself. The center rail is the one exception, and it is cut with small tenons that fit into 1/4-in. by 1/4-in. grooves on the stiles.

By cutting the tenons and mortises 1 in. deep instead of 1-1/4 in. deep (the full width of the rails and stiles), you leave material to cut the 45-degree haunches at the joints. These haunched tenons not only look more refined, but they also allow you to rip the rail and stile grooves full length on the tablesaw.

Use a 1/4-in. dado setup to cut the grooves on the inside faces of the rails and stiles. For the middle and upper rails, you also remove the inside portion of the groove so that the glass can slide into place after the door has been assembled.

Using the same dado setup and a simple jig that fits over the tablesaw to hold the stiles upright, raise the blade to 1 in. and cut a tenon slot on the ends of the rails. Adjust the fence so that in two passes you’re able to leave the 1/4-in.-thick tenon.

At the bandsaw, trim down the width on the inside of the tenon by 1/4 in. You’ll notice that this leaves the tenon length 1/4 in. shy of mating correctly. A simple miter jig clamped onto the rails and stiles helps guide the chisel for the 45-degree cuts.

Once you’ve milled and trimmed a center panel for the bottom of the door, the door can be glued up. When the glue dries, you’ll still have to remove the inside of the groove on the upper portion of the door where the glass will be installed. Do this with a straightedge and a box knife, then clean it up with a chisel.

The final touch to this door is to install the muntins. Cut them 5/8-in. wide and center them on the square upper portion of the door. Then use a small saw to cut the 45-degree miters that accommodate the muntins. Once the two pieces press-fit into place, lay one across the other and mark the centers. Cut a 1/8-in. groove where the two cross each other. When installed, a few drops of glue at the groove and on the mitered ends, along with a little tension from the door itself, hold everything in place.

Once the glass slides in, small pieces of molding are used to secure it.

Final touches

All that’s left to do is to hang the door and apply the finish and hardware. I used an oil varnish from Waterlox to give this piece a natural look and to provide protection. The hinges I used are antiqued, solid brass H-hinges from Horton Brasses, and the knob is a Shaker-style bronze knob from Colonial Bronze.

After you’re done, open the cabinet, reach in the drawer, and fix yourself a cup of tea.

Fine Woodworking Recommended Products

Blum Drawer Front Adjuster Marking Template

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in